Archetypes of Adventure: Conan and Elric

by Bill Ward

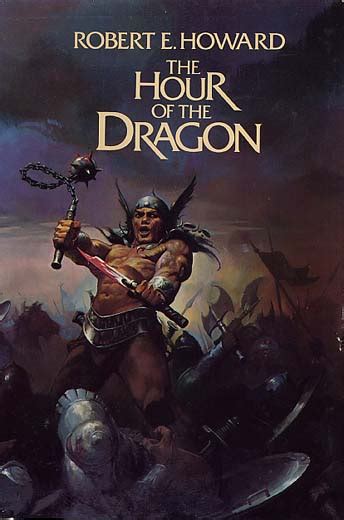

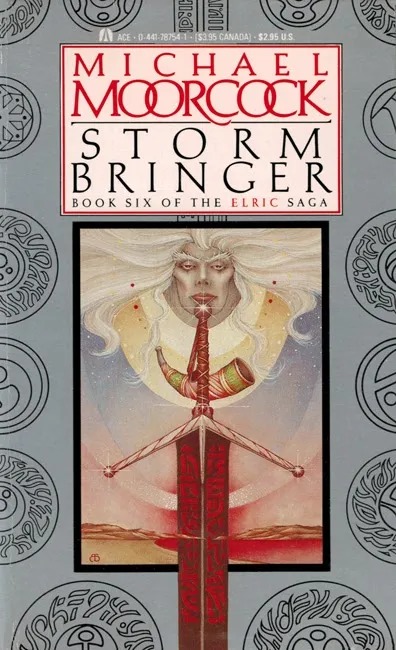

Few characters in fantasy are as iconic as Conan the Cimmerian: black-haired barbarian warrior with the deadly grace of a panther and the impressive physique of a prize fighter, a wanderer, a reaver, and a king by his own hand. Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melnibone perhaps rivals Conan in terms of iconic status (if not exactly in market saturation), perhaps in part due to his deliberate inversion of many of Conan’s characteristics. Elric is slender and frail where Conan is the brawny image of impervious good health, Elric is a sickly albino reliant on concoctions of medicinal herbs to function, while Conan voraciously drains wineskins and gnaws beef-bones. Elric becomes both master and servant to a magical black sword, whereas Conan fights with whatever suits his setting or whatever is at hand — including the aforementioned beef-bones! The physicality of both is key to their characters, and both represent an extreme of appearance and function that renders them iconic in the fullest sense of the term: it isn’t just that they are famous creations, it’s that they both carry a symbolic weight that is integral to not only their character, but to every story in which they appear or, to some extent, to every kind of story that draws on them for inspiration.

The genesis of both characters stems from Robert E. Howard’s and Michael Moorcock’s writing of magazine fiction, with its emphasis on pacing and accessibility. The more easily and immediately comprehensible an element of such stories, the better it works in a short form that may appear out of sequence or across separate venues – for in the case of magazine short fiction, every single story will be someone’s introduction to reoccurring character or world. Hence, iconic or archetypal characters – the sort that are not only easy to convey with a few words but, just as importantly, create a strong image for illustration* – are a real key to building a following for these kinds of serial heroes. The criticism frequently leveled upon this kind of fiction is that it lacks ‘well-done’ characters, which always seems to strangely miss the necessary point that magazine short adventure fiction must distill story elements down to the level of the instinctive and symbolic in order to get on with entertaining through plot. One might as well ding Jane Austen for how she handles battle scenes, or lament the lack of supernatural horror in Proust, than to talk about flat characters in sword-and-sorcery.

The other element of this magazine approach that influenced the shape of both of these characters is that both are told out of any kind of chronological order, and grow organically over subsequent tales. Already the earliest Conan and Elric stories establish certain very strong traits and characteristics and biographical facts that serve as a foundation to develop further details – and both are much more fully realized than, for example, another beloved, very iconic magazine character, Sherlock Holmes, whose initial incarnation undergoes some fairly extensive ret-coning as he goes from unrepentantly uncultured calculating machine to someone who plays the violin and must occupy his higher faculties with regular visits to the opera! This non-linear ‘career hopping’ of Howard’s and Moorcock’s allows not only great opportunities for foreshadowing (it’s really easy to foreshadow something you’ve already written years ago) such as found in the ‘first’ Elric novel (Elric of Melnibone) or the many mentions by Conan that perhaps he’d like to try his hand at kingship, but it also actually creates some further opportunities for characterization by highlighting watershed moments in the development of each character.

Of the two, Conan is the more developed in his magazine incarnations – though Moorcock has the advantage of coming back to his character years later in longer works. But Conan demonstrates real growth as a character, and does so in a completely non-linear fashion, simply by virtue of the small developments in the character over the course of key individual stories. His moral development in “The Tower of the Elephant,” or his assumption of a leadership role in “Black Colossus,” reveal two integral aspects of his character that are there in both earlier and later stories. For Elric, a more static character, subsequent tales or stories about his past are less opportunities to demonstrate character development than to enlarge upon his eventual fate — to fill in not only his tragic ‘origin story,’ but to re-engineer it in light of the dramatic culmination of his saga. Like Holmes, Elric too was killed by his creator far too early in his career, however, unlike Doyle, Moorcock’s apotheosis for Elric informs much of what he would go on to write about the character over many more stories and books.

And, while Elric is deliberately an ‘anti-Conan’ in many ways, mostly in his physical inversion of the Cimmerian, but also in the angsty nihilism of a character who doubts his own free will, both characters are more similar than they may at first appear. Both are complete outsiders – even the Elric who sits upon the Ruby Throne he was born to occupy is a strange alien to his own people – and both are naive when appropriate . . . either for the character, or the plot. Conan’s naivete is that of the fish-out-of-water barbarian wandering in civilized lands, whereas Elric’s is primarily the foolishly misplaced trust he shows in his cousin and rival. The cynical, demon-conversing, sorcery-using Elric is very different from the magic-hating, practically-minded Conan, but both experience the occasional ‘knowledge gap’ when the story demands it. In fact, that’s one of the necessary ingredients of such stories, because we as the audience are also strangers, and need to have information parceled out to us in a way that makes it palatable and comprehensible.

We are told that Conan broods, has “gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirths” but seldom do we really see it. This isn’t a flaw in characterization, this is the difference between biography and fiction – the Conan we experience is a man of action set free of his larger burdens through motion, through doing things. Perhaps if we were to visit him in his cups, all ablutions poured out, a little longer after the events of “Beyond the Black River,” or if the winged apes had left him alone after slaying his lover in “Queen of the Black Coast,” we would have gotten more of a taste of this aspect of his character.

Elric, of course, has a problem with losing himself in action – because it also means losing his will, his very soul, to the black vampiric sword that fills him with a wild rush of stolen power. When he shows elation at this quickening of his impulses, he is always depicted as regressing somewhat to the cruel and inhuman ways of his people, and as always with Elric the specter of regret and self-loathing resurfaces afterward. No winged ape slew his lover, that was done by Elric’s own blade, twisting in his hand to gloat over one more soul lost, one more move made on the chessboard of fate that contains Elric’s own doom. This may be one of the biggest differences between the two characters, surface characteristics aside. Conan’s hyper-competence in the physical space of violent action offers him a real freedom – perhaps even a ‘gigantic mirth’ – and his instinctive, ‘in the zone’ adventuring is a more potent elixir than any Melnibonean concoction. Elric’s own superhuman abilities only serve to further reinforce that he is not his own master, and to damn him further as those close to him pay the price for his power.

Both free Conan and unfree Elric of course have an ultimate master – their respective authors, or perhaps the dictates of adventure fiction itself. Each author has a radically different approach to arriving at a kind of common ground – Conan’s actions, even when he isn’t the main character, grow out of his motivations as a character, and Howard is so skillful at this that even his most coincidence-laden, plot-heavy, or formulaic Conan stories never feel as if they are on rails, they have an authenticity born out of the character himself. Moorcock does almost the opposite, somehow legitimating fantasy tropes by deliberately drawing attention to them and to the plot itself, paradoxically enlarging the importance of his character by simultaneously rendering him but one of a billion incarnations across a vast microcosm of space and time.

“Let me live deep while I live; let me know the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on my palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flame and crimson, and I am content. Let teachers and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.” “The Queen of the Black Coast”

Elric was not interested in such philosophizing. “Dream or reality, the experience amounts to the same, does it not?” The Sailor on the Seas of Fate

Here is the true common ground between Conan and Elric, enough to render them the closest of kin. Whether deriving freedom or damnation through action, for both characters the action itself has definite meaning – just as storytelling itself has an intrinsic, non-diminishable, value. For all his nihilism and self-doubt, Elric does not consider his dreamlike life an illusion – in fact, he’s almost impatient with the notion, when hearing it discussed by other aspects of the Eternal Champion. Such a concept, of course, would invalidate the suffering that is at the heart of the character, and for that alone Elric would have to dismiss it. But further than that, for Conan and Elric both, it’s we the reader who might entertain such solipsistic conceits in some post-modern litfic or sci-fi story, but when it comes to the serious business of sword-and-sorcery, it just won’t fly. Because to believe in them as we do, they have to believe in what they do: something Conan and Elric, and Howard and Moorcock, demonstrate time and again over an impressive collection of classic tales.

*Or comic book artist, as so much of the popularity of both characters stems from their depiction in comics. In fact, Elric’s first comic book appearance was in back-to-back issues of the 1972 run of Conan the Barbarian.

Header image graphics by Brom.