Elric and the Cosmology of Dungeons & Dragons

by Bill Ward

While Gary Gygax’s influences for Dungeons & Dragons were many, something of course reflected in the most influential fantasy fiction recommended reading list of all time, Appendix N, certain authors and works stand out. Jack Vance’s magic-infused Dying Earth stories, Fritz Leiber’s roguish romps with Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, the Weird Tales and pulp powerhouse mashup of Robert E. Howard’s Conan tales, and modern fantasy’s great urtext itself, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, all occupy the top shelf of inspiration for Gygax’s revolutionary game. Michael Moorcock’s sword-and-sorcery stories exerted no less a profound influence on the shape of D&D – most especially its cosmology – as did Vance’s spells, Leiber’s thieves, Howard’s barbarians, or Tolkien’s elves, dwarves, and hobbits (err . . . halflings).

Moorcock’s fantasy worlds are absolutely full of colorful characters, weird monsters, strange artifacts, and supernatural wonders to the point where they might serve as a veritable warehouse of fantasy ideas. From the world-shatteringly potent (and potentially cursed) artifacts like the vampiric hellsword Stormbringer, the reality-altering Runestaff, or the dreadful Eye of Rynn and Hand of Kwll, to the menagerie of monsters, Chaos creatures, races (lost or otherwise) devils, elementals, gods (dead or otherwise), and varied nations (human or otherwise) – there is enough material in the average three-act Moorcock sword-and-sorcery novel to furnish an RPG supplement.

In recently rereading the core books of Moorcock’s Elric Saga, I was struck by the many little details that could have perhaps settled in Gygax’s imagination and found their way into D&D (more to the point, AD&D and beyond, which is generally what I am referring to throughout this article when I use ‘D&D‘). There is the metal golem that Earl Aubec fights in the Fortress of Dawn, the black cat familiar of Drinij Bara, Elric’s numerous animal and elemental summonings, the use of a Common Tongue throughout the Young Kingdoms, or Moonglum’s flinging a jar of inflammable oil onto the undead King From Beneath the Hill. Certainly, my party always left town accompanied by the sound of oil flasks clinking against their iron rations – it was like having a first-level mage (or three) in your backpack!

Moonglum’s firebombing took place in “Kings in Darkness,” a very early Elric story that was reprinted in one of the Moorcock books Gygax specifically cites in Appendix N: The Stealer of Souls (before finding a more permanent home in The Bane of the Black Sword). Also in the same story, Elric prepares a potion that renders him and his companion immune to edged weapons for a short period of time – a very D&D thing to do, and a reminder of just how much potion consuming is going on in the Elric tales. Elric, of course, is normally physically weak and enervated, and thus takes various concoctions of herbs merely to function, but he also occasionally whips up something special or quaffs a brew offered by another – such as the revivification potion Myshella gives him upon his return from the tower of Voiloidion Ghagnasdiak in The Vanishing Tower (alternate title, The Sleeping Sorceress). And speaking of enervation, how about earlier in the same book when the Cold Ghouls of Limbo suck the energy out of Elric and leave him helpless – it isn’t exactly XP-draining, but the latter concept seems like a rather elegant way to model the notion of being robbed of your life’s essence.

Energy-drained Elric is thrown into a spell-warded prison with The Burning God, a Chaos elemental of fire, an actual minor deity – and is only saved by an intervention of a God of Law. This scene neatly encapsulates what I think the major influence of Moorcock’s sword-and-sorcery, in particular the Elric stories, had on D&D. Two aspects of the game’s actual cosmology are prefigured here: one, the inclusion of Law and Chaos* as universal forces involved in a perennial conflict in which mortals themselves must profess an allegiance and, two, the interaction of the world of mortal adventurers with the grand forces of gods, cross-dimensional beings, multi-planar conspiracies, and world-altering events. Elric, a being owing allegiance to Chaos, wielding an evil-forged, god-killing sword, does battle as a Champion of Law, not only slaying (or, rather, destroying their presence on his plane) various Dukes of Hell in a final apocalyptic battle that sees the very land transformed, and also ushers in a new Age of Earth after a universal destruction (and that’s not even mentioning the time when he teamed up with three other Champions Eternal to kick off something that looked a whole lot like the Big Bang!). Heady stakes for your typical murder-hobo.

D&D‘s alignment system is surely directly inspired by Moorcock’s multiverse of a Law and Chaos perennially vying for influence in a universe continually course correcting in accordance with a Cosmic Balance. Gygax’s system rather brilliantly cross-references Good and Evil with Chaos and Law – with Neutral to fill in the gray areas – and presents players not only with a literal moral compass, but links their very personal behavioral modes and methodologies to a larger universal significance. A player character doesn’t have to swear allegiance to a patron like Elric’s Duke Arioch of Hell for his own worldview to directly affect what he can and cannot do in-game – D&D‘s alignment system has the beauty of scaling up or down depending on the nature of the campaign and the goals of the characters.

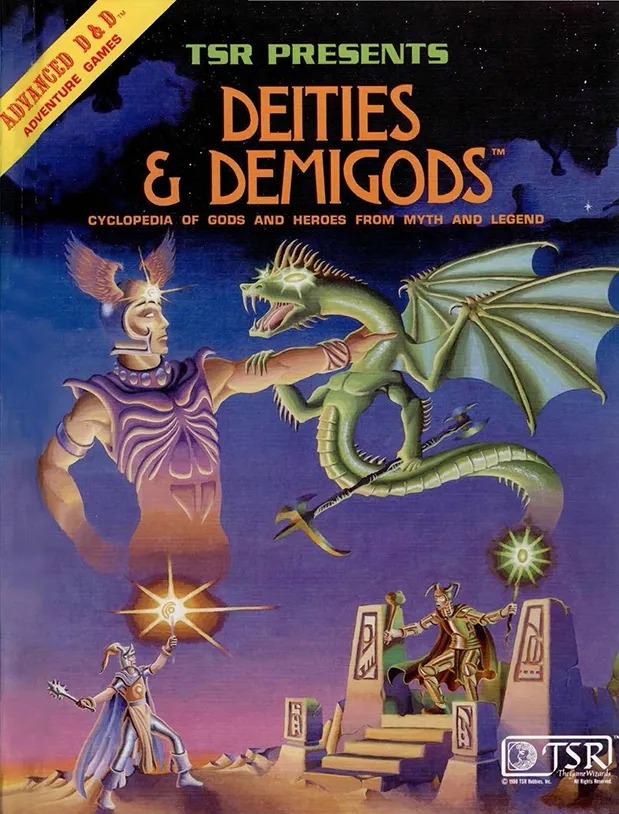

And scale has to be one of the other big influences Moorcock’s universe-spanning stories had on Gygax. While Conan or Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser occasionally tangled with gods or cosmic forces, no sword-and-sorcery cycles of that era had the kind of gonzo grandeur of Moorcock’s plane-hopping, world-destroying, or god-slaying tales. From the Demon Princes and Arch-Devils of the Monster Manual to the extra-planar oddities of Fiend Folio and the epic heroes and literal gods (including Moorcockian ones, in its initial release!) of Deities & Demigods, the big picture vision of Advanced Dungeon & Dragons was of an unlimited universe-as-dungeon-crawl experience where the players just might one day aspire to stand toe-to-claw with the Fenris Wolf, Maglubiyet, or Demogorgon himself. For that wild cosmic scope and sense of huge-scale possibility, I think Moorcock’s sword-and-sorcery tales in general and Elric in particular were a major influence on Gygax’s creation.

*Moorcock freely acknowledges his own inspiration for his cosmic battle of Law and Chaos in Poul Anderson Three Hearts and Three Lions; but clearly it is Moorcock’s grand take on the subject that has inspired D&D.