What is the Dying Earth?

by Bill Ward

“A dim place, ancient beyond knowledge. Once it was a tall world of cloudy mountains and bright rivers, and the sun was a blazing white ball. Ages of rain and wind have beaten and rounded the granite, and the sun is feeble and red. The continents have sunk and risen. A million cities have lifted towers, have fallen to dust. In place of the old peoples a few thousand strange souls live. There is evil on Earth, evil distilled by time . . . Earth is dying and in its twilight . . .”

~ “T’sais,” The Dying Earth, Jack Vance

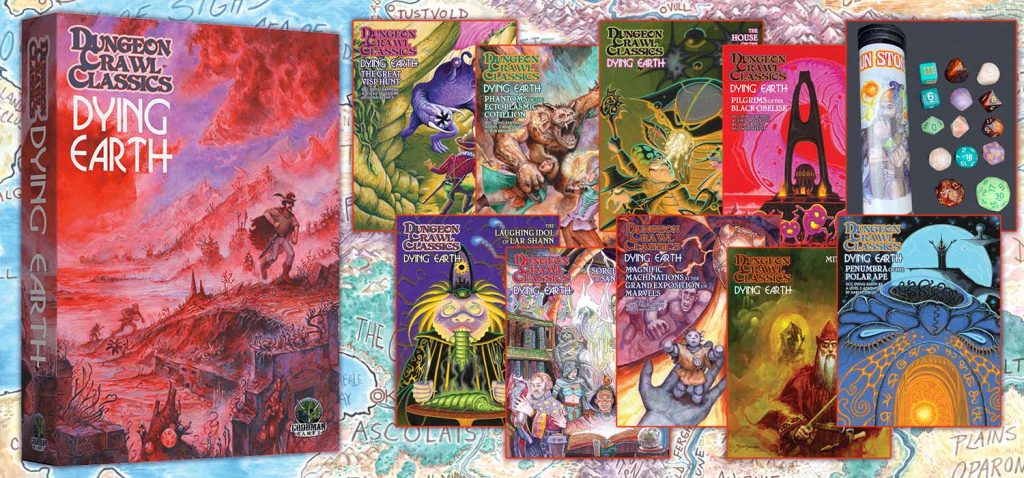

The title of a book and a series of books, the umbrella setting of multiple stories, and the name of a sub-genre of fantastic fiction – any or all of these meanings might be invoked when one speaks of ‘The Dying Earth.’ It is, of course, the name of Jack Vance’s 1950 collection of loosely connected stories set in his eponymous world of the far, far future of our planet – a time so vastly removed from ours that it is a never-never land of magic, demons, forgotten technology, and strange human civilizations. The Dying Earth treats us to the exploits of powerful wizards and charming rogues, cursed creations and determined adventurers – all set against a wildly imaginative backdrop of an entropic world grown strange and perilous.

Vance wrote many other stories set in his far future Earth with its slow-rolling red sun “drifting across the universe like and old man creeping to his death-bed,” most famously those of his rogue-to-end-all-rogues, Cugel the Clever. The four books that comprise Vance’s Dying Earth series (The Dying Earth, The Eyes of the Overworld, Cugel’s Saga, and Rhialto the Marvellous) are among the most widely-read of any in his prodigious output, and the series is as closely linked with Vance’s name as are his much more numerous science fiction novels. While nearly all of his work is stamped with Vance’s distinctive voice – a bemusedly semi-formal and ironically detached style that is equal parts playful and cynical, rich with antique words and rhythmical in its slightly off-kilter syntax, at once both spare and lyrical – it is his Dying Earth stories that see him cavorting in the twilight spaces between absurdism and fabulism in a manner so unforgettable that it has become forever linked with his name.

While Vance’s The Dying Earth provides a label for the sub-genre itself, it was by no means the first to utilize such a setting. In looking at its antecedents, however, it is important to make the distinction between the predominantly fantastical or ‘science fantasy’ aspect of the Dying Earth sub-genre, and other works that fall squarely into the science fiction camp. H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine is an excellent example of the latter, describing not only a strange far-future society, but glimpsing the death of the Sun itself and the subsequent freezing over of the world. Likewise, one can find the pessimism of impending doom in apocalyptic fiction, starting with Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. Neither of these works, or the dozens before or since that treat with far futures and doomed civilizations in a rational or realistic mode, can truly be placed beneath the Dying Earth label, however.

One major work that certainly can and must be considered as part of – or perhaps even ‘the start of’ – the Dying Earth sub-genre is William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land. Published in 1912, Hodgson’s nightmare future of the remnants of a defeated humanity huddled in one final city in a world of permanent darkness and supernatural peril certainly ticks the ‘science fantasy’ box. Much bleaker in tone than Vance’s far-future, The Night Land goes even further toward capturing the notion of an ‘antique future’ with a challenging, deliberately antiquated prose style. Written well before genre labels in science fiction and fantasy became their own discreet bailiwicks, The Night Land exuberantly combines the speculative elements of Hodgson’s era – everything from ghosts to telepathy to electric guns – into one wild amalgam of world-building.

Clark Ashton Smith’s Zothique story cycle, written mostly in the 1930’s, is much closer to the Vancian mode than The Night Land. All of Smith’s major story cycles take place in tucked away corners of unreality – the ancient legendary continent of Hyperborea, doomed Atlantis, a dark fairy tale version of Medieval France – and Zothique, the last continent of a dying and depraved planet, is no exception. As with Vance, Smith’s world is one where science has perished into myth, and reborn magic reigns supreme. Comparing the two works highlights one of the core aspects of this sub-genre, demonstrating why it is different from science fiction – it describes a future unmoored from the past. Wells’ time traveler found a future that spoke directly about the present day, the future worlds of Vance and Smith play with deep time as a thematic element, they invert the trope of “long ago and far away” to transport their impossible worlds out of the past and into the future.

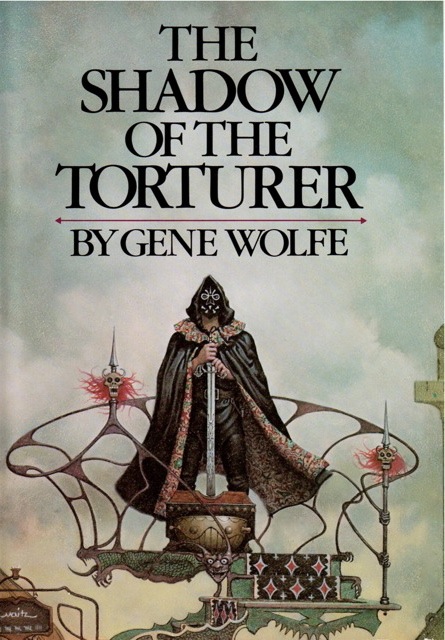

The greatest modern successor to Vance’s Dying Earth is Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun pentalogy, starting with The Shadow of the Torturer in 1980. As with any of the authors mentioned previously, Wolfe freely borrows inspiration from those that have come before in service to a work that is wholly his own unique vision. Framed as a hero’s journey, unreliably narrated in the first person (a hallmark of Wolfe’s), Wolfe’s far future Urth is lushly described using the semi-obscure vocabulary of the past in a manner that conveys the antiquity of his world with every line. A subtle work inviting multiple readings and interpretations, The Book of the New Sun adds a layer of metaphysical speculation, puzzles of identity and memory, and suggestions of shifting timelines to the now-traditional trappings of monsters, rogues, ‘magic’ swords, and senescent civilizations grown strange beneath the waning light of a dying star. Unlike his predecessors, however, Wolfe’s own dying red star isn’t thematically decorative, but a major plot element of the entire series – giving us a Dying Earth facing the possibility of resurrection and metamorphosis.

Any and all of these works skirt the traditions and conventions of genre fiction and use the far future setting to imaginative advantage in ways wholly unique to each author. Vance’s sardonic roguery, Hodgson’s grim endgame, Smith’s baroque neverwhere, and Wolfe’s textual virtuosity all offer distinct inflections on the common ingredients of the Dying Earth. Emerging from a time when the light of rational inquiry was busily illuminating the farthest corners of prehistory and the very planets themselves, when imaginative literature began to separate into distinctive camps, and when unprecedented technological development promised an exciting and progressive future for all of humanity, the Dying Earth genre represents the ultimate rebellion – an escape not into a secondary world colored by our own past, but a leap into a impossible far future in which all of our present triumphs are forgotten and blown to dust.