This October, Take a Trip Into “The Willows”

by Brian Murphy

Writing something original about “The Willows” is about as fraught a proposition as having something original to say about The Lord of the Rings. First published in 1907, Algernon Blackwood’s tale is widely recognized as, if not the finest horror/suspense story in the English language, certainly in the conversation. Many have extolled its virtues, and none other than H.P. Lovecraft considered it to be the finest supernatural tale he had ever read. Nevertheless I’ll make an essay of my own here as to its potency, and why it’s worth reading.

Not all horror need be jump scares or gore. The most effective stories in the genre build and sustain a sense of dread. Of being watched, turning quickly, and finding nothing behind you. But the terror persists. In his non-fiction study Danse Macabre, Stephen King described a hierarchy of horror writing that placed terror at the apex (fear of the unknown/inner dread), followed by horror (outwardly showing horrible things), and finally, splatter (the gross out). Wrote King: “I recognize terror as the finest emotion and so I will try to terrorize the reader. But if I find I cannot terrify him/her, I will try to horrify; and if I find I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out. I’m not proud.”

There is terror in “The Willows.” No gore to speak of, unless you count a vaguely sketched corpse or two. Not any full-monty depiction of the unnamable, ghosts and goblins and zombies lurching through the night, the stuff of horror. Its power is in suggestion.

Adding to the terror of the story is its “based on true events” authenticity. Blackwood drew upon personal experience for “The Willows,” two separate events a year or so apart centered around the same haunted isle. From a 1938 introduction to the tale: As I look back to revive old memories… of a journey down the Danube in a Canadian canoe, and how my friend and I camped on one of the countless lonely islands below Pressburg (Bratislava) and the willows seemed to suffocate us in spite of the gale blowing, and how a year or two later, making the same trip in a barge, we found a dead body caught by a root, its decayed mass dangling against the sandy shore of the very same island my story describes. A coincidence, of course!

The outline of the story is as follows: Two men take a canoe trip into the wild, albeit one very unlike Deliverance. They embark in Hungary, boating down the river Danube, first slowly but later at a rapid clip as the current sends them racing toward the Black Sea. Buffeted by winds and seeking shelter they stop for the night on a small island, scarce an acre in size. The island is noteworthy only for being overhung and choked with willows. The two men set up camp in a hollow in the middle of the island and light a small fire with what driftwood they can scavenge.

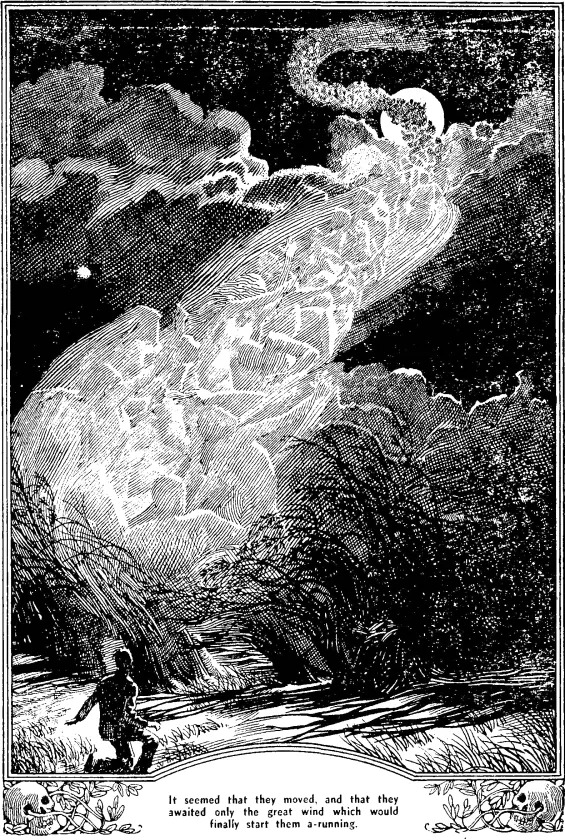

Then the weirdness begins. The men begin to feel a sense of something off in the press of the willow bushes, which crowd in upon them with a weird sentience. And the willows seem to close in upon them, in frowning rows. These are not willow trees but willow bushes; thick, omnipresent, choking, whispering.

They next experience two strange occurrences from without: One sees a figure which they believe to be a human corpse, rolling over again and again in the turbulent water, but which turns out to be an otter. Or so they think, they cannot trust their senses. Then they see a man standing on a flat-bottomed boat, shouting dire warnings lost in the roaring wind and crossing himself as he drifts by in the dark, the setting sun a crimson flame. And the forebodings intensify.

Blackwood was a master of psychological terror, casting doubt on our perceptions, of whether what is real is real, or only a partial glimpse of a wider (and darker) reality. There are other dimensions in Algernon’s universe. We are never 100% certain if the men’s feelings are tied to some actual external presence, or comes from within. When they encounter sabotage–their canoe has a hole in the bottom, a paddle goes missing, food disappears–it appears something is visiting them… but it may be the involuntary actions of the men themselves, who take turns watching as the other sleeps. Sometimes they find themselves lost in dark reveries, lost in a semi-dream state, of which they have no clear recollection. The narrator grasps at logical rationalization of the weird events; the odd holes in the ground that they find around their tent must be hollows left by the action of the wind, the pressing force from above as they lie awake in their pitiful tent at night, a branch. One sees shapes, human-like but demonic, in the firelight, but they must be cast by the flames. And so on.

The terror builds. One night rolls into two after the canoe requires patching and the wet pitch must dry and set. At first neither man wants to talk about the oppressive terror, fearing that what they say may manifest. But finally, they crack. One of the men, a Swede, shouts down the other’s increasingly far-fetched rationalizations. “’You fool!’ He answered in a low, shocked voice, ‘you utter fool. That’s just the way all victims talk. As if you didn’t understand just as well as I do!’” The terror is spoken aloud, and the pressure builds. They realize their only hope for survival is to keep perfectly still; their insignificance and silence may save them. No action will.

If an island of willows sounds ordinary, that is part of the appeal. The story requires no moldering edifice out of a gothic, where all signposts point to “haunted.” It’s a true weird tale, pre-Lovecraft. The two men have stumbled into an alien presence in an otherwise ordinary place. It is ancient, Other, hostile, and brooks no human company. It has no place in this world … and it requires sacrifice to appease.

There is no backstory, no reason given for this feeling, or this place; no witch burned at the stake who has laid a curse upon the land, nothing so common as Satan or Baphomet pulling the strings of fear. Just a place where men should not be. We feel this hostile strangeness as we read Blackwood’s tale and wonder if we, too, are reading something we’re not supposed to. It lingers in the mind, disquieting.

“The Willows” is a quintessential horror story that should be read every October. It’s available on Project Gutenberg, get to it. If you dare.

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.