No Darkness Without Light: Roger Zelazny’s Jack of Shadows

by Bill Ward

“I am Jack of Shadows!” he cried out. “Lord of Shadow Guard! I am Shadowjack, the thief who walks in silence and in shadows! I was beheaded in Igles and rose again from the Dung Pits of Glyve. I drank the blood of a vampire and ate a stone. I am the breaker of the Compact. I am he who forged a name in the Red Book of Ells. I am the prisoner in the jewel. I duped the Lord of High Dudgeon once, and I will return for vengeance upon him. I am the enemy of my enemies. Come take me, filth, if you love the Lord of Bats or despise me, for I have named myself Jack of Shadows!”

Godlike beings in competition, the bending of natural laws, a multiplicity of strange environments, the collision of magic and science, characterization rooted in myth and metaphor, and stakes of cosmological or world-shattering import – Roger Zelazny’s most popular fiction, be it his Amber Series, his brilliant Lord of Light, or the subject of this essay, Jack of Shadows, showcase the inherent fascinations that inform much of his work. Not that a grab-bag of story elements alone could possibly define an author – particularly one as creatively unrestrained as Zelazny – but if you should see such a grab-bag flung over the back of a man in a hurry, shades black, cigarette canted, perhaps as he races with seemingly suicidal speed atop a growling chrome hog though the log-jammed streets of conventional narrative, then you’ve just spotted one of the wildest storytellers of the twentieth century. Run after him!

Jack of Shadows, Shadowjack. Say his name in shadow, and he will hear it. Shadows are his realm, his kingdom, the source of his power. And Jack himself is a Power, one of the many beings infused with uncanny magic that rule the darkside of the world like petty pagan gods. He is also a thief, or the thief; a darer of impossible deeds and filcher without parallel. We meet him in Twilight, that region of the sideways, unrotating world where the two halves of permanent dark and permanent light mingle in a perpetual dusk. Jack is strong here, for Jack’s rule was absolute “wherever light and objects met to make a lesser darkness.” But Jack, mid-plot to steal the Hellflame, the bride price for the woman he desires, is betrayed, captured, surrounded with mirrors, and neutralized. Without shadow, Jack is just Jack (well, almost), and he is beheaded for his reputation and apparent intentions.

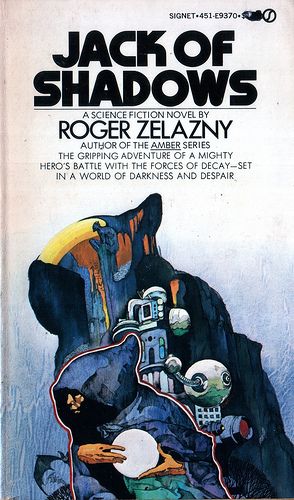

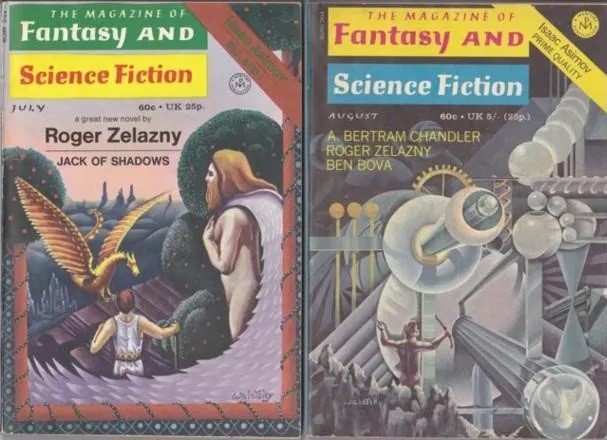

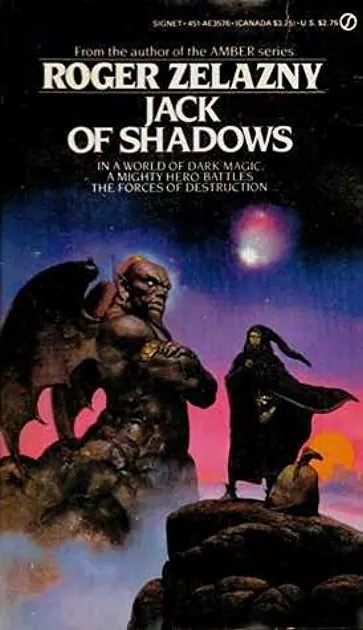

And Jack is reborn, darkside, re-coalescing in a new body atop the rancid Dung Pits of Glyve at the West Pole of the world. Darkside Powers have multiple lives just as they have innate sorcerous abilities and a mastery of magic. All at the price of having no soul. Thus are the events of Jack of Shadows set in motion, Zelazny’s 1971 novel (serialized in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and published in book form the same year) of a (our?) world divided by light and dark, science and magic, and the colossal events set in motion by the only Power that could possibly master both. Combining a pulpily-paced picaresque adventure with a plot suggestive of the cosmology of an unfamiliar culture glimpsed through a dark lens, Jack of Shadows reads like it’s half a science fiction tale set in the classic mode of the hyper-competent protagonist taking on all comers, and half the metaphorical fantasy adaptation of a creation myth revolving around some trickster god. This is perfectly fitting for a book about duality, about halves becoming wholes – light and dark, science and magic, immortality and death, love and hate. Jack, whose revenge-quest becomes the explosive element of disruption on a world that is static and unmoving, isn’t just the central pivot of all of these polarities, he’s their literal embodiment – the darksider who requires light for his magic, the sorcerer that masters science, the conscienceless man who meets his own soul while on his way to destroy the world.

The first half of the novel sees Jack leaping from peril to peril as he navigates his way through the lightless enemy territory of his fellow darksiders – who all hate him, by the way – finally culminating in his imprisonment in a refractive jewel worn around the neck of his arch-rival, The Lord of Bats. The Lord of Bats has done even worse, however, in taking beautiful Evene, she of the union of a darkside father and dayside, or mortal, mother, as his wife. Jack, having recently lost his head for love of her, accounts it one more devastating betrayal for the tally of pain he will revisit upon his foes. Naturally, he escapes, and with all the dark mobilized against him he slips eastward, beyond Twilight, into the land of permanent blazing light and cold, rational science. There, bereft of his powers and under the alias Doctor John Shade, he will search for Kolwynia, The Key That Was Lost, with the aid of a supercomputer on a university campus.

Zelazny’s unity of setting, plot, theme, and character is as tightly intertwined in this fast-paced novel as in the best short fiction. For example, as Jack slinks and stalks over darkside a hunted man, we are treated to certain details about his world. Above both halves of the planet are critical, artificially-created protections – dayside’s Force Field ensures that it isn’t burned to a crisp by perpetual sunlight, and darkside’s magic Shield prevents its meager warmth from bleeding off into space. Jack notes the world feels cooler than it ought. What seems a piece of world building, a memorable image reinforcing the unique setting and underlining the theme of light and dark duality, is almost immediately revealed as a critical plot element for Jack’s escape – and also provides a demonstration of his character. Abusing the most sacred agreement of the darkside by breaking the Compact between the Powers for the maintenance of the Shield, Shadowjack reveals himself as outsider and rulebreaker. Such a willingness to flirt with global disaster is also a strong piece of foreshadowing for the eventual trajectory Jack’s journey of revenge will take. When Zelazny throws a narrative stone he isn’t aiming to get a pair of birds, he takes out entire flocks, and time and again through Jack of Shadows off-handed references, seemingly minor characters, events, or impressions, even philosophical discussions, reveal themselves has having multiple levels of significance to the overall story.

Jack of Lies, Jack of Evil. When Jack has his revenge with the aid of impossible forces, it’s abrupt, surprisingly off-camera, but that is because the stakes and scope of the entire tale have changed just as Jack’s power has changed – just as the readers’ impression of Jack has changed. The vagabond Master Thief becomes a brutal conqueror, killing his enemies again and again in an attempt to be rid of them permanently, and enslaving Evene with magic. But in this latter half of the book we are introduced to Jack’s soul – it turns out all darksiders have one, they’ve just discarded them as useless – and finally we begin to see Jack change, as chinks start to appear in his amoral psychology, and a little light creeps in. Even as he hatches his most monumentally destructive scheme, he begins to experience the pangs of conscience that had once rendered all those short-lived, fast-changing daysiders such a mystery to him. As he disrupts the machinery of the world, attaining a near-god like power, he is also paradoxically growing more human.

Zelazny parcels out the clues and hints with the subtly of the maestro building toward a finish, all while leaping from point to point in the story with breakneck pace. He is sparing of description in all but the most crucial of scene-building passages, and Jack’s plans, thoughts, even past are doled out to the reader on a need-to-know basis. All of this serves to cohere the narrative space tightly in upon itself, rendering the barrier between the exterior world and the interior psychology of the protagonist a permeable and flimsy one. For such a fast-paced book, Jack of Shadows benefits from the careful reading approach one might use for a tightly-wound short story. And even as lean a work as it is, there are still mysteries left unresolved when the book is closed – in fact it ends ambiguously, on an unresolved action. There are possible hints at the cyclical nature of events, that the cataclysm of the climax perhaps reflects that which froze Jack’s world on its side in some distant past age, that maybe Jack himself was always linked in some way to the forces that defined the world – whether they be interpreted as sober engineering or demonic sorcery. It seems entirely appropriate to Jack of Shadows that I can’t really say with any certainty either way; in much the same manner that a darksider and daysider might dispute the nature of the stars or the true power deep within the earth while never once agreeing, but somehow both managing to get it right.