Short Sorcery: C.L. Moore’s “Shambleau”

by Bill Ward

“And this conflict and knowledge, this mingling of rapture and revulsion all took place in the flashing of a moment while the scarlet worms coiled and crawled upon him, sending deep, obscene tremors of that infinite pleasure into every atom . . . And he could not stir in that slimy, ecstatic embrace—and a weakness was flooding that grew deeper after each succeeding wave of intense delight, and the traitor in his soul strengthened and drowned out the revulsion—and something within him ceased to struggle as he sank wholly into a blazing darkness that was oblivion to all else but that devouring rapture . . .”

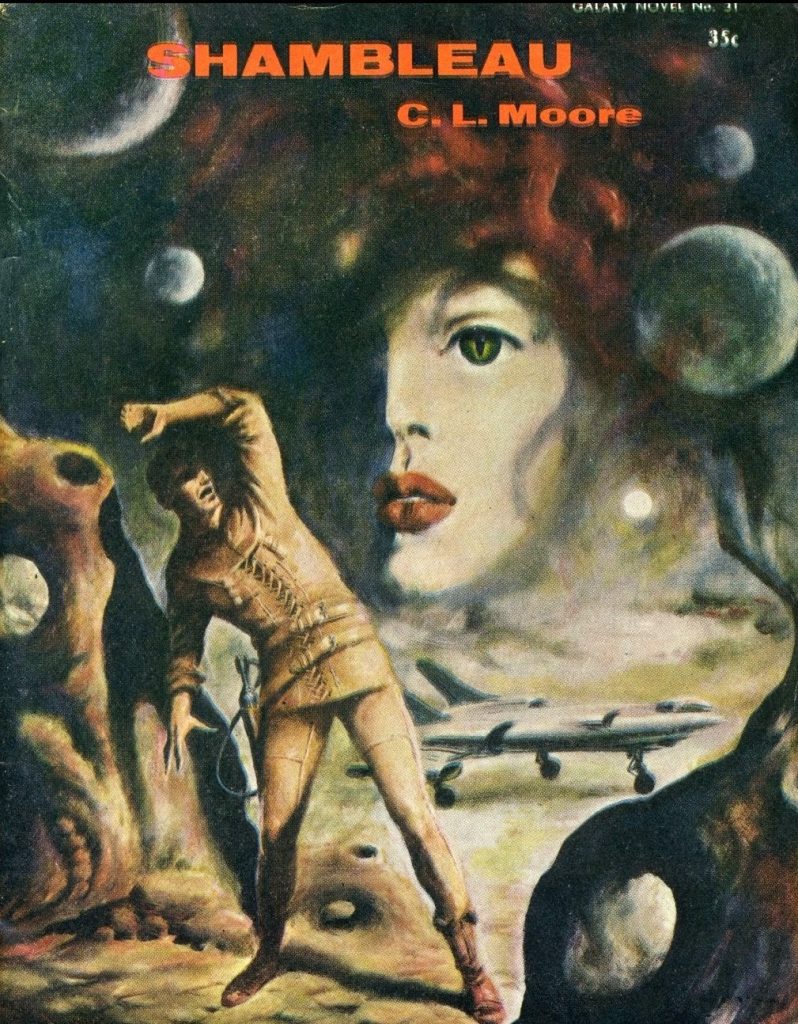

A young bank employee decides to use her free time to practice her typing skills – after so many tedious iterations of ‘a quick brown fox’ her mind wanders and she begins to play on the page, quickly describing a scene partially inspired by a poem, establishing a premise for the story that would be her first, and most renowned. The story was “Shambleau,” which debuted in Weird Tales in 1933 and won the young bank employee, writing under the semi-anonymous initialization of her full name of Catherine Lucille Moore, an instant and devoted following. Her subsequent work, both solo and in the powerhouse paring with her future husband Henry Kuttner, would guarantee her inclusion in the ranks of the Grand Masters of genre fiction.

Another first associated with “Shambleau” is the introduction of Northwest Smith who, together with Jirel of Joiry, are Moore’s most famous creations. It’s been said many times that Smith is the prototype of every space rogue from Han Solo to Mal Reynolds, and it is interesting to see the genesis of this character sauntering through the dusty streets of a Martian town in this, Moore’s first story. Smith was conceived in response to Moore’s need to complete the equation of her initial scene – an angry crowd chases a vulnerable figure through the hot red streets of Lakkdarol, but who would stand up to them? Part Wild West gunslinger with cold gray eyes and quick-draw heat gun, part footloose pulp adventurer exiled from home and forever wandering exotic lands (very) far from the everyday, Smith is a solid archetype around which to spin a yarn, a character that Moore would revisit in over a dozen stories which built on the formula first seen in “Shambleau.”

Smith burns a line in the sand and fixes his deadly gaze on the Martian rabble pursuing the turbaned waif – they are disgusted and confused by this, but dare not cross the spacer. And it isn’t so much the steady leveled sidearm that clears the crowd, it is Smith’s semi-comprehending formal claim on Shambleau – for that is her name, and the name of all her people – that drives them away, leaving him bewildered by their pivot. “We never let those things live,” says one of the mob and Smith, as he leads the oddly alluring and, now obviously non-human, woman away to the safety of his flat, ponders the strangeness of what just happened.

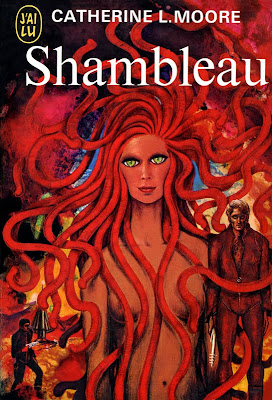

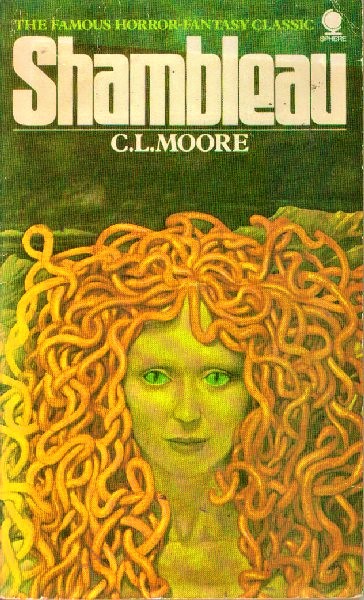

But we, the audience, know more or less exactly what is going on – for Moore tells us in an introduction that establishes a deep-time background for her future pan-human solar system of Earthmen and Martians and Venusians all as off-shoots of the same human race, together sharing certain ancient memories, that what Smith is dealing with is medusa, or a medusa, or, most accurately, the member of a mysterious and deadly species upon which the medusa legends of all the inhabited planets are based. The quick strokes of exposition are practically all we ever get for Smith’s universe beyond the seasoning of colorful details sprinkled throughout the tales, and these mentions of ancient astronauts and lost continents like Atlantis and Mu establish more of a kinship with the kinds of worlds conjured by Robert E. Howard than Burrough’s Barsoom.

But most importantly, the upfront sharing with the audience of the mysterious woman’s identity is a marker of just the sort of stories Moore writes. “Shambleau” creates a dramatic tension far more effective than a mere guessing game as to the creature’s origin or analog by telling the audience in the first paragraph the nature of the being with whom Smith is entangled. The mystery unfolds anyway, as the strength of Moore’s powerfully descriptive prose exerts a fascination on the reader akin to the fascination Shambleau herself exerts on Smith – Moore, in writing of one man’s temptation, is herself performing the ultimate in writerly seduction.

In rendering eroticism a key element of horror – and make no mistake, spaceships and ray guns aside, “Shambleau” and many if not most of the Northwest Smith stories are Horror fiction – Moore was both ahead of her time and at the head of her class. Bela Lugosi’s seductive presence as a pre-Hays code cinematic Dracula was only two years old at the time of “Shambleau’s” publication, and despite his example most horror was still firmly rooted in the monstrous or the mutational (ie. the Wolfman, the Invisible Man, etc.). A tale featuring an alien succubus and a man of action who is ultimately powerless against her charms wasn’t typical of the entertainment of the day, whether in or out of the pulps, but what really pushes “Shambleau” from novel premise into the realms of genre classic is the execution. Simply put, Moore is an enchanting writer, capable of crafting imagery and conveying emotion in so effective a manner that plot is a secondary concern of hers, her dramatic story beats and resolutions are rooted in theme and metaphor, she does not focus so much on ‘what’ as she does on ‘how.’

And it is the ‘how’ of “Shambleau” that elevates it above the extremely simple framework of its plot – indeed a plot summary could almost make it seem like a vignette: “a spaceman unwittingly saves the life of medusa, and is ensnared by her alien powers of fascination until saved by an ally.” But, like a master chef crafting something wondrous from the simplest of ingredients, Moore understands balance and proportion. One example is the simple and stark color palette of her story. The early repetition of red, color of both arousal and viscera, pleasure and pain, life and death – the red town, red pavement, red slag, red segir whiskey; as well as the scarlet of Shambleau’s attire – offers not only a startling contrast to the only other vivid color in the story, the cat’s-eye green of medusa’s enslaving gaze, but also primes the reader for the horrible revelation of just what lies beneath the turban so tightly bound to Shambleau’s head:

“The red folds loosened, and—he knew then that he had not dreamed—again a scarlet lock swung down against her cheek . . . thick as a thick worm it fell, plumply, against that smooth cheek . . . more scarlet than blood and thick as a crawling worm . . .”

And the characterization of Smith is perhaps more subtle than it appears at first glance. He is no white knight saving a damsel in distress (“…he did not mean to give up his life for any girl alive.”), rather he is a hard man in hard circumstances that nonetheless prefers to act with human decency. In his confrontation with the mob he is careful, at least half his posture is bluff and he has no desire to kill. As he removes Shambleau to safety he is met with disgust by passersby, and experiences a kind of shame intermingled with his simple confusion – he is literally returning to his flophouse with vixen in tow; a strange being whose sexual charms are immediately apparent to him, but who is universally despised as tainted and revolting by everyone else in the story. The context of the forbidden and shameful juxtaposed with the sexual connotations that inform every interaction between Smith and Shambleau create not only a titillating tension of forbidden lust, but strongly underpin the actual existential threat of the medusa as a corrupter and destroyer of virtue to the very depths of the soul. Smith, a literal outlaw, is essentially forced by his own nature to ignore the inexplicable reactions around him which should have served as a warning, if only to assert his independence from the herd. He is a supremely competent man filled to the brim with self-reliance – which ironically just makes him more blind to the ways in which he is vulnerable.

Shambleau is installed in Smith’s temporary quarters while he attends to other business, and he forgets about her for the day, assuming she’ll just leave on her own after treating herself to some of his food tablets. Several times in the story Smith leaves and returns to Shambleau, each time the stakes are higher and his peril more imminent. His first trip back culminates in a drunken pass on an eager Shambleau – whom Smith recoils from in sudden horror after an initially intense attraction. For all her soft curves, her feminine vulnerability, her novel sexuality, Shambleau is somehow beyond non-human – she is inhuman. There is a dark depth to her, but Smith still sees her more as animal than monster, as something vulnerable that needs protection, and a shift occurs between them as he disengages from their embrace. Smith, we are again shown, is a man of control, mastering his liquor and his own urges and listening to the inner voice of his own conscience. There are lines he will not cross, just like the blaster-burn he left in the street that morning.

That night, in his second test, she comes to him in a dream, tasting him, subsuming him in a flood of exquisite ecstasy and gut-rolling revulsion, paralyzing him with her embrace. Smith resists in his dream at the very level of his soul, again asserting his higher human faculties to assert a degree of self-control even in the face of a dream of temptation. But what he fails again to comprehend is the true nature of Shambleau, and, awakening, the dream world is dismissed by the rational man of action, in the same way his temptation of the night before was waved-away as the effects of strong drink. Smith, rooted to a direct, masculine reality so intense it has scarred and burned him the same shade and texture of the battered leather of his flight suit until he, perhaps ironically for a spaceman, seems almost an autochthonic avatar of the solid world of terra firma, fails to heed the warnings of the numinous or his own subconscious creeping suspicions of dread.

He tries to communicate with her, and we are treated to more foreshadowings of evil intent on Shambleau’s part (“Some day I—speak to you in—my own language,” she promised, and the pink tongue flicked out over her lips, swiftly, hungrily.) The new relationship is one of generalized concern as Smith attempts to distance himself (with mixed success) from his earlier attraction – upon his next return to the flat his overall interest is simply in getting Shambleau (who he even refers to once as ‘child’) to eat, and to somehow find safety for her once he himself is gone from Mars. Smith may not have understood the full ramifications of claiming Shambleau as his own, but he is acting on them nonetheless.

Smith is waiting for his Venusian friend Yarol, fellow smuggler and captain of the blockade runner Maiden. Surely it is no accident that these two dangerous, powerful men are masters of a ship named for a virgin bride, a potent machine with an innocent name, a feminine energy they treat lightly enough to make into a mascot and servant. Smith assumes the same with Shambleau, assumes that, having made his decision to bury his urges, he is in control of the situation – and meanwhile the beautiful-seeming creature stares and smiles at him from the corner of his room, biding her time until she and Smith should lock eyes in a fatal, final encounter…

“All this in a graven instant—and after that a tangled flash of conflicting sensation before oblivion closed over him for he remembered the dream—and knew it for nightmare reality now, and the sliding, gently moving caresses of those wet, warm worms upon his flesh was an ecstasy above words—that deeper ecstasy that strikes beyond the body and beyond the mind and tickles the very roots of soul with unnatural delight. So he stood, rigid as marble, as helplessly stony as any of Medusa’s victims in ancient legends were, while the terrible pleasure of Shambleau thrilled and shuddered through every fiber of him; through every atom of his body and the intangible atoms of what men call the soul, through all that was Smith the dreadful pleasure ran. And it was truly dreadful. Dimly he knew it, even as his body answered to the root-deep ecstasy, a foul and dreadful wooing from which his very soul shuddered away—and yet in the innermost depths of that soul some grinning traitor shivered with delight. But deeply, behind all this, he knew horror and revulsion and despair beyond telling, while the intimate caresses crawled obscenely in the secret places of his soul—knew that the soul should not be handled—and shook with the perilous pleasure through it all.”

Pleasure and revulsion, ecstasy and dread; Moore scintillates in the climactic confrontation between Smith and Shambleau, dancing along a tightrope stretched between the twin gulfs of the sensual and the sickening with an expert grace that almost makes it look easy. It’s an encounter that Smith loses and one that, ultimately, is a conflict with himself – it’s the very corruption of his inner being, the ultimate denial of his ability to dictate life on his terms. The final, haunting line of the story brings all of this into focus. Smith’s partner Yarol finds him in flagrante horrifico with the coiling mass of slick crimson worms which suck the very essence from him with a ruthless hunger, and does the very sensible thing of shooting Shambleau dead with a ray gun while aiming at its reflection in a mirror. He provides some exposition about the terrible creature, how they enslave and destroy their victims, and how some of those victims go willingly into that deadly embrace. How some of the survivors of such encounters spend the rest of their hollow lives seeking only to return to such seductive annihilation.

Yarol asks Smith to promise to kill any Shambleau he should ever encounter in the future, the very second he realizes the medusa’s true nature. Smith, spared a horrible fate by dumb luck, shouldn’t even have to be told to do this, and certainly shouldn’t struggle to agree. But struggle he does, a man of such magnificent self-control that his word is more binding than a contract, cannot give his word, because he no longer knows himself with any certainty. Smith fights back the “gray blankness that held all horror and delight—a pale sea with unspeakable pleasures sunk beneath it,” and resolves himself to swear to his friends request, meeting his gaze with steady gunslinger’s eyes “pale and resolute as steel.”

‘”I’ll—try,” he said. And his voice wavered.”

Even in the moment of supreme decision, even with first-hand knowledge of the fell nature of the corrupting pleasures of the gorgon, Smith falters in his formerly ironclad resolution. Encapsulating something of the powerlessness of the addict, suggesting the inner war brought about by irresistible temptation, Smith has been wounded more profoundly here than from any suffering of his wild outlaw life as, for the first time, the self-mastery that allowed him to prevail in every crisis has itself been shattered by an inexplicable desire more powerful than the will of one strong man standing rigid against the tide. Insightful, carefully wrought, powerfully written – C.L. Moore’s “Shambleau” is so much more than the sum of its parts – though, thankfully, its own darkly hypnotic energy builds to a crescendo of catharsis, rather than corruption, and readers left wanting more of the same have a dozen further tales to choose from, none of which will annihilate their soul.