Our Appendix N Archeology and Adventures in Fiction series are meant to take a look at the writers and creators behind the genre(s) that helped to forge not only our favorite hobby but our lives. We invite you to explore the entirety of the series on our Adventures In Fiction home page.

Ghosts, Ghouls, and Little Green Men: EC Comics and Appendix N

by Mark Bishop

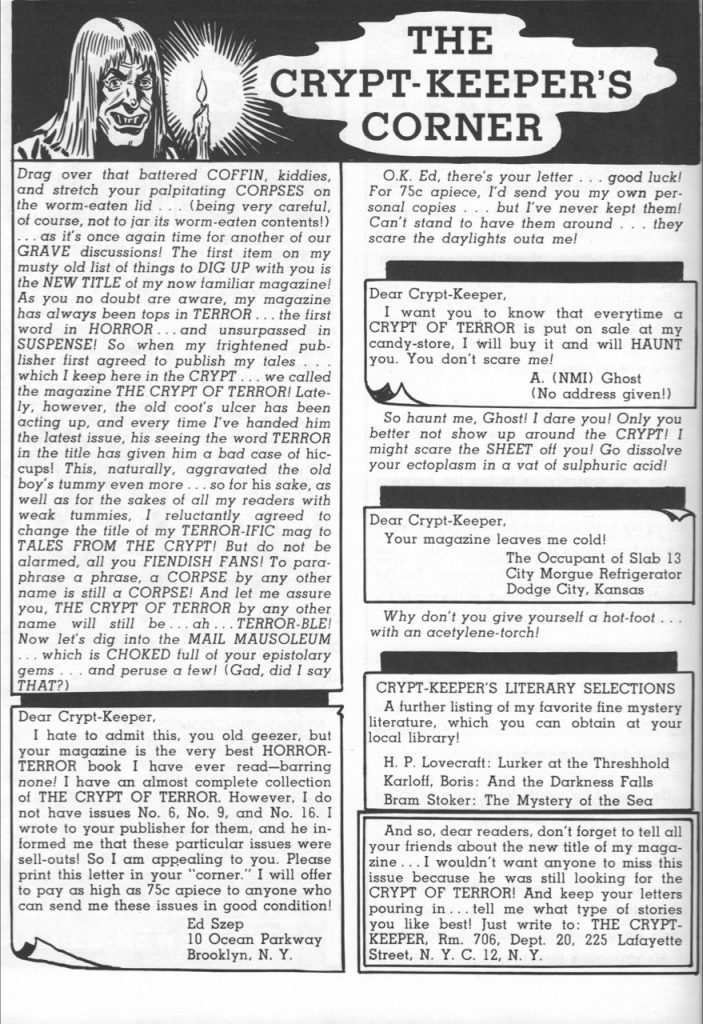

“Drag over a casket kiddies and place your palpitating body upon it… being careful not to jar it, otherwise its unfortunate occupant might GO TO PIECES! If you have time to KILL, let’s have a chat…”

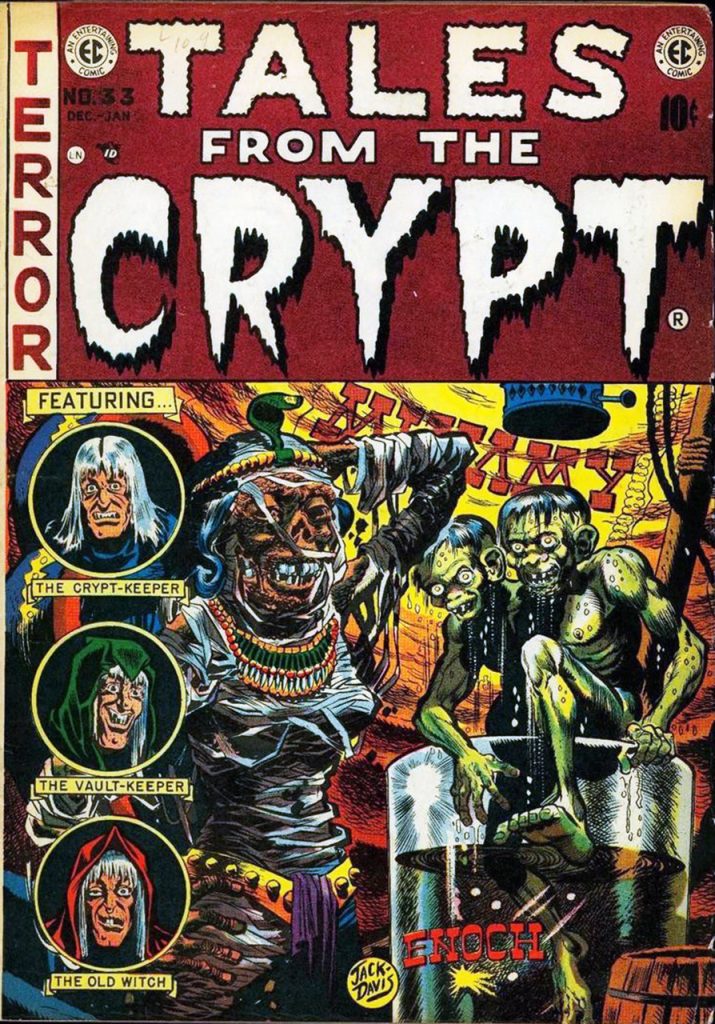

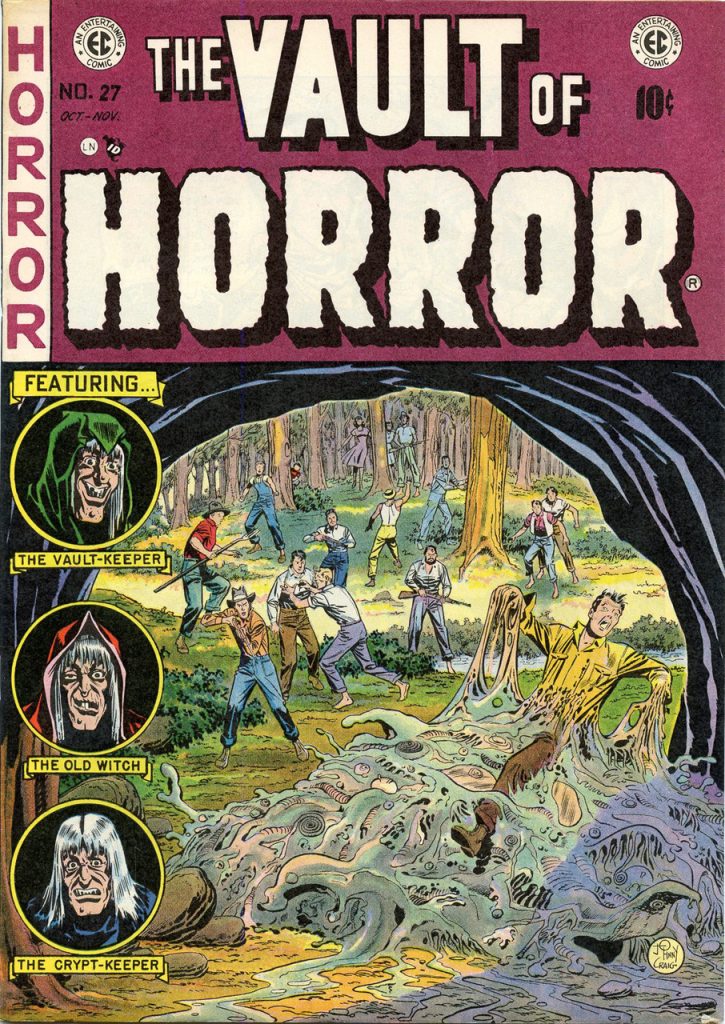

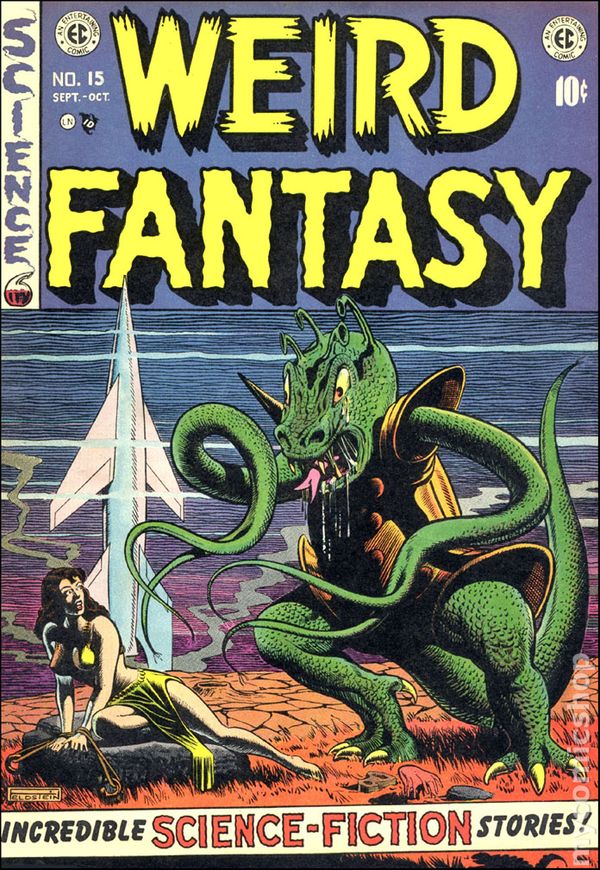

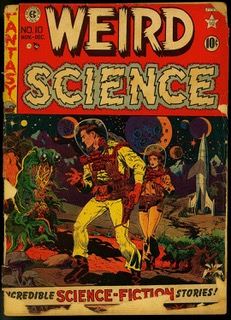

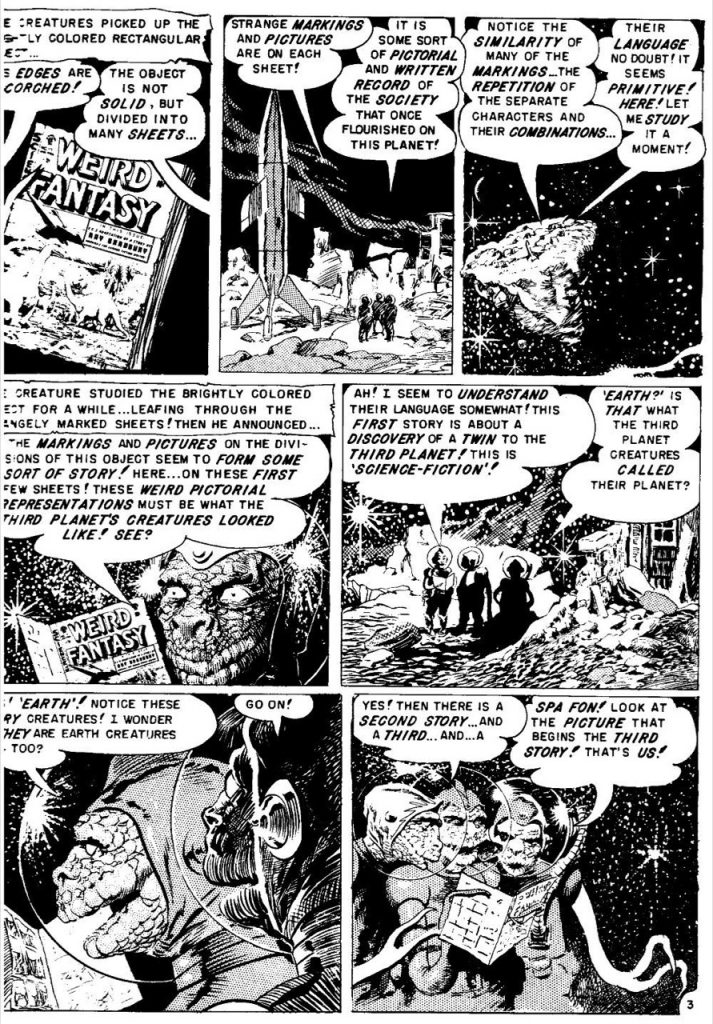

Thus begins the Crypt-Keeper’s Corner, the letters page in the June-July 1950 edition of EC Comics Crypt of Terror. You could be forgiven if you mistook that dramatic introduction as the opening salvo from any game master at any table-top role-playing game. In fact, it’s also fairly easy to see how Gary Gygax, the main co-creator of Dungeons and Dragons (and an entire gaming industry) would fess up to being influenced by the art and storytelling found within the comic books of his formative years. But they are not just any old comic books that he mentions; Gary took the time to single out the creative output of one particular company among the veritable sea of comic books being printed at the time. Yes dear readers, the creeping tendrils of Tales from the Crypt, Weird Science, and Vault of Horror have been christened part of the root system beneath the mighty sequoia that is Dungeons and Dragons. EC Comics are among the very first influences Gary mentions in the now-famous Appendix N, a bibliography of sorts on page 224 of the 1979 AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Before we allow ourselves to be dragged into the murky swamps by those same rotting tendrils, let us remember exactly what Gary Gygax said in the opening paragraphs of Appendix N.

APPENDIX N: INSPIRATIONAL AND EDUCATIONAL READING

Inspiration for all the fantasy work I have done stems directly from the love my father showed when I was a tad, for he spent many hours telling me stories he made up as he went along, tales of cloaked old men who could grant wishes, of magic rings and enchanted swords, or wicked sorcerers and dauntless swordsmen. Then too, countless hundreds of comic books went down, and the long-gone EC ones certainly had their effect. Science fiction, fantasy, and horror movies were a big influence. In fact, all of us tend to get ample helpings of fantasy when we are very young.” After mentioning a few other items, Gary goes on to say, “Upon such a base I built my interest in fantasy, being an avid reader of all science fiction and fantasy literature since 1950.

It’s interesting to note that Gary Gygax, being born in 1938, would have been twelve years old in 1950 when he began his journey into fantastic fiction. What makes that age pertinent for our explorations here is that comic books experienced a sea change in that same year when Bill Gaines and EC Comics began their “New Trend” of more sophisticated (and gruesome!) comic books, changing the landscape of the comics publishing field (in ways they didn’t expect) forever. At the same time that comic books had become more literate, horrific, and more popular than ever, along comes the perfect demographic in twelve-year-old Gary Gygax. If by his father’s stories he had developed a proclivity toward imaginative storytelling, then in 1950 it’s no wonder that the stories told in EC Comics would have found themselves in that young boy’s wheelhouse. To get a sense of the times, in 1949, comic books reached more people than television, radio, or magazines, with estimates from several sources putting the number somewhere around 750 million issues of comic books being sold in that year alone. The early 1950s were a booming time for the medium. This number would drop significantly by the mid 1950s due to the vilifying of comic books, senate hearings on violence within them, and the implementation of the Comics Code Authority, but for now, young Gary Gygax would have felt right at home in these anthology-style comic books that mimicked in many ways the attributes of the pulp magazines that came before them.

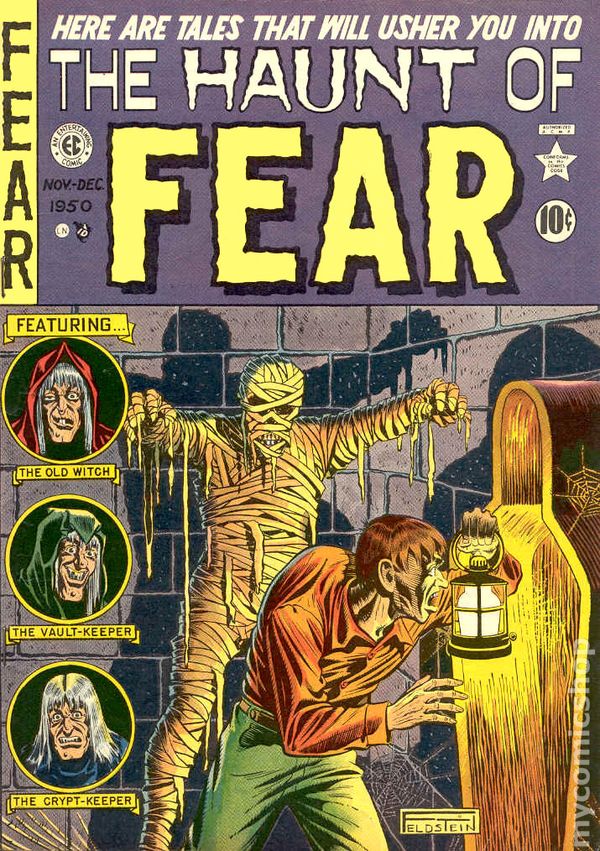

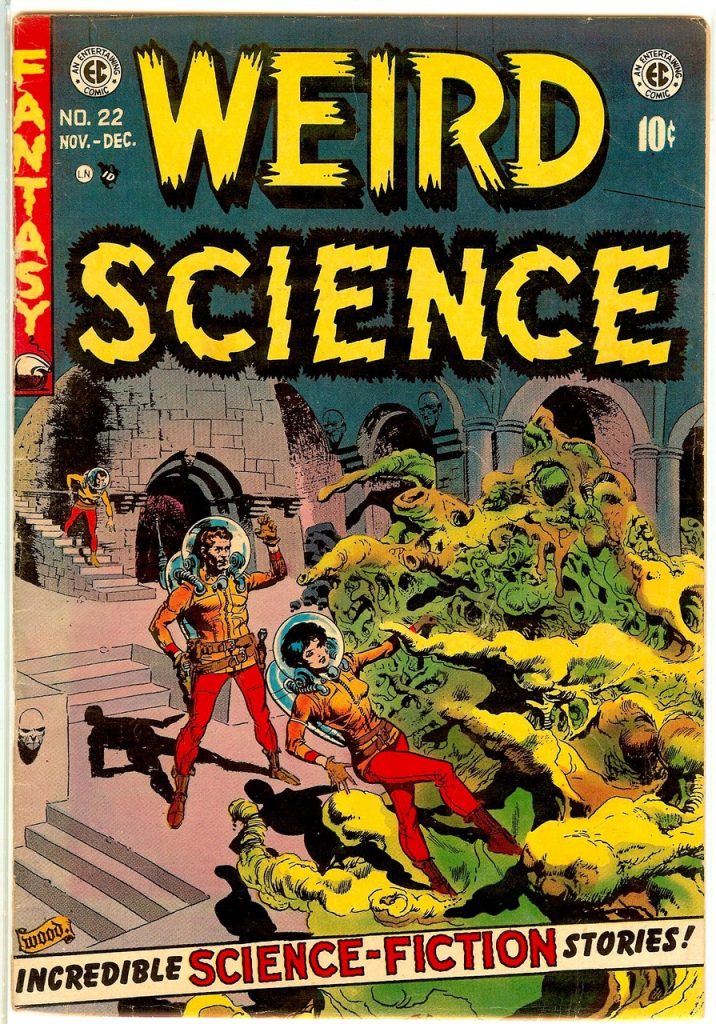

So what are EC Comics and why did Gary Gygax mention them alongside the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs, H.P. Lovecraft, J.R.R. Tolkien and other luminaries of fantastic literature? While he gives us little to go on in his concise words of praise, it’s worth a little curiosity and conjecture on our part regarding this particular influence, to see what connecting tissue we can recognize between them and the world’s most famous table-top role-playing game. Though Gary’s exact thoughts may be lost amongst the decayed leaves of a distant season, we won’t have to do much digging to arrive at some interesting relating artifacts. Regarding the question of, “what are EC Comics?”, comic book historians of every ilk would be quick to tell you that the New Trend books published by William Gaines’ Educational Comics between 1950 and 1956 are among the best that this genre of literature has ever produced. When “Bill” Gaines reluctantly took over the family publishing business after his father’s death in a boating accident in 1947, he inherited a line of comic books that frankly were nowhere near the tops of the sales charts. As a matter of fact, the company was in the red to the tune of about a hundred thousand dollars. (1) Quickly he began to assemble a new, younger staff of artists and writers. Tired of following the comic book trends set by others, the new staff began their own “new trend” of comic books, replacing the old bland titles with exciting and edgy titles like Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. It would be easy for me to get into the weeds here about the success of these books and why, but suffice it to say, soon much of the entire comics industry would be abandoning their old ideas and following the trends set by the creatives at EC Back in 1938, comics had begun their superhero phase. In 1947, crime comics became all the rage. But in 1950, about the same time that Gary Gygax began to cultivate a love for fantastic literature, the anthology horror and science fiction titles of EC were the high-water marks that the other companies attempted to emulate.

While these comics are cited as an influence early on in Gary’s tip of the hat, there is no mention of which titles, in particular, might have been his favorites or “had their effect.” It would be fairly safe one would think that among all of EC’s output of horror, science fiction, western, war, crime, suspense, and humor comics (Mad anyone?), that it would have been the horror and science fiction magazines that would have been the most obvious choices. We may never know. I was recently able to ask his son, Ernest Gary Gygax Jr. if he remembered anything his dad might have mentioned about comic books in general. His answer was, “Sadly, he never talked about the comics nor did he have any left when I was growing up.” Regarding the other literature his dad lists he offered, “As to his book collection though – I read through all the books listed in the Appendix N in my youth.” So here again, it’s up to you and I to take out our Sherlock Holmes magnifying implements, adjust our deerstalkers, and examine the clues laid before us.

As has already been mentioned, there was certainly a pulp-like feel to the EC comic books. Each book was an anthology, containing many text-heavy stories. The art was certainly a step above other comic books of the era and more on par with the wonderful illustrations seen in the pulps. And then there were the actual stories themselves. Most were written by Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, Al being an amazing artist in his own right. In the early years, the two men were writing five or six stories per issue for five different books each month! It’s very hard to imagine having to come up with that much story material in such a short amount of time, but in Grant Geissman’s book, Tales of Terror: The EC Companion, Al Feldstein reveals in a 1996 interview how the ideas for the new trend stories began and how the task was accomplished.

“We used to talk about The Inner Sanctum, The Witch’s Tale… and those old radio shows. So I said, “What about horror? There’s been some stuff, but nothing really horrible, really scary. Let’s do that.”… Bill got very excited, because now he was into something he could lay his hands on. Bill had a weight problem, and he was taking diet pills which… would keep him up at night… So he started to read. I don’t know exactly how it happened, but from my plotting my own story, he wanted to give me ideas. He started to plot with me. He’d bring me springboards, and I would listen to them… I’d have to go up and construct the fill and make it into a six pager. The next plot would be a seven pager, tomorrow’s an eight pager.” Grant then asks Al Feldstein about that process:

“GG: What would the basic plot be that he would give you? Give me a sentence what it might be like?

Feldstein: A guy kills his wife and has to get rid of the body, so he orders crates of ketchup—to make the body more palatable. That was a swipe, that’s a Lord Dunsany story (Two Bottles of Relish).”(2)

In an interview for the EC fan magazine Spa Fon in 1969, Bill Gaines corroborates that method. “In the early days we used to lift a lot of springboards because before we got to the point where we could do our own plotting, we were lifting plots we remembered from things we had read many years before in the pulps, never dreaming that anybody would recognize them. I remember the very first story in Weird Science #12… called “Lost in the Microcosm”… I lifted it from something I remembered twenty years earlier, when I was a ten year old kid, that I’d read in Amazing or Astounding Stories. How the hell did I know I was lifting a classic that everybody in science fiction knows as ‘He Who Shrank?’ (laughs).”

Along with Lord Dunsany, other Appendix N list authors would be, ahem… “adapted” by Gaines and Feldstein in their writing sessions. Fritz Leiber’s “Nice Girl With Five Husbands” would inspire “A Timely Shock” in Weird Fantasy #10 (1951). Manly Wade Wellman’s “The Kelpie” would inspire “He Who Waits” in Weird Fantasy #15 (1952). H.P. Lovecraft’s “In the Vault” would inspire “The Grave Wager” in Vault of Horror #16 (1951), and his work “Cool Air” would inspire the story “Baby… It’s Cold Inside” in Vault of Horror #17 (1951). Lovecraft’s creation, the fabled Necronomicon, also plays a vital part in the story “The Black Arts” in Weird Fantasy #14 (1950).

In order to keep up with the insatiable demand for new stories (and because he couldn’t sleep), Bill Gaines became a voracious consumer of exactly the same kinds of literature that young Gary Gygax might have been pursuing at the same time, though for different reasons. Grant Geissman in his book relates that, “Sources of inspiration for many of EC’s science fiction stories include early issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and the 1940’s and 1950’s era SF anthologies edited by Groff Conklin.” (3) Not only did Gaines and Feldstein borrow story seeds and ideas from the pulp writers of the past, they hired stories from currently working genre writers like Otto Binder, Harlan Ellison, and Ray Bradbury. Bradbury alone had 27 stories adapted to various EC Comics. (4) Along with these authors are also 15 Grimm’s Fairy Tales (also mentioned in Appendix N) adapted to EC’s over-the-top manner.

As mentioned above, EC Comics were considerably more text-heavy than their competitors on the newsstands. (Al Feldstein said in an interview that, “The old joke was that I got to writing such heavy captions and balloons that all the characters had to be drawn with a hunchback.”) Aside from the initial splash pages, each page usually consisted of a minimum of seven panels; each panel filled with copious plot advancement and description, even to the last page when the story would come to its end, usually in a panel of no other visual distinction beyond being the last panel in the story. There was no grand heroic pose or clue that the reader would see coming, rather, in a subtlety belying a comic book, the zinger would arrive without warning, wrapping up the narrative in some unexpected (and sometimes grisly) way, much like Rod Serling would make popular in his The Twilight Zone series years later. In his 2008 book, “The Ten-Cent Plague”, author David Hajdu interviewed comics legend Robert Crumb about the impact of those books. He offered, “To me, EC was the culmination of everything that kind of came before it in comics. The art quality was the tops, and they had the best storytelling in comics. They were also the most serious comics in the fifties, and they were forbidden, and that made them all the more exciting.” (5)

Robert Crumb does not at all exaggerate when he says that the books were “forbidden.” As the EC books and all their imitators flooded the market throughout the early to mid 1950’s, each trying to out-shock the other, the new proliferation of more mature-themed comic books with their profuse gore and violence caught the nervous eye of many in authority, including a noted psychiatrist and author by the name of Dr. Fredric Wertham. In his book, The Seduction of the Innocent, he laid out the case that these types of comic books were contributing to the rise in delinquency among youths. This is another case where it would be easy to wade into the weeds and away from our subject, and we simply have other fish to fry, so, suffice it to say, young Gary Gygax better be enjoying these comics while he still can!

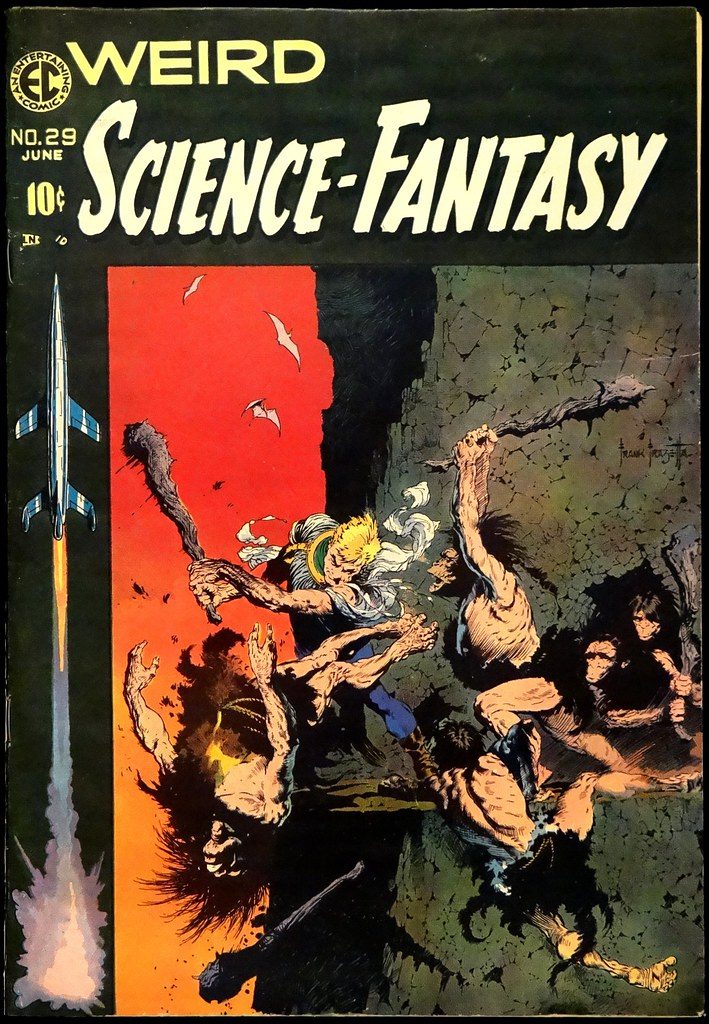

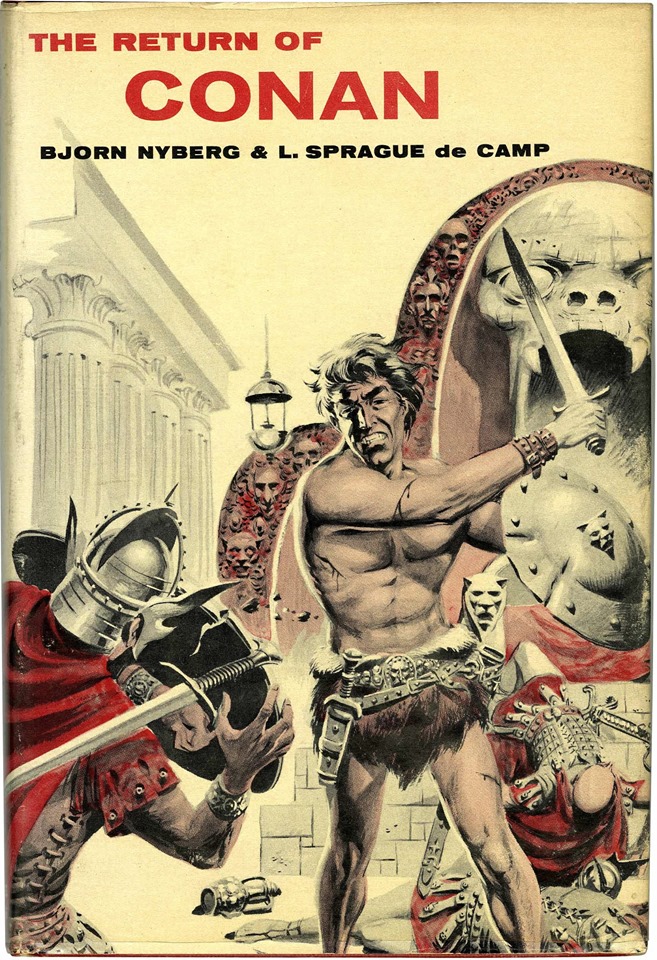

Robert Crumb is also correct when he says of EC Comics that “the art quality was the tops.” A listing of the artists who worked for EC in their heyday reads like a “whos-who” of talent. We could easily take many different routes here also, but I think our best course of action in order to attain our goal is to focus on the ones who have at least some connection to Gary Gygax’s Appendix N. Perhaps at the top of that list would be one of the nation’s most prolific and profound artists of Robert E. Howard’s Conan series, and that would be Frank Frazetta. It would be hard to overstate Frazetta’s impact on fantasy illustration in his day. Any quick Google image search reveals a plethora of Frank Frazetta Appendix N book covers which bring us into the worlds of not only R.E. Howard and L. Sprague de Camp, but also Edgar Rice Burroughs, Lin Carter, and Andrew J. Offutt, Appendix N listees all. It is highly likely that Gary Gygax was introduced to the work of Frazetta early on being an “avid reader” of these authors. He may have encountered him in the pages of EC Comics first. Frazetta’s early work for EC Comics often came though his friendship and association with other artists of that day who became known in the EC offices as “The Fleagle Gang.”

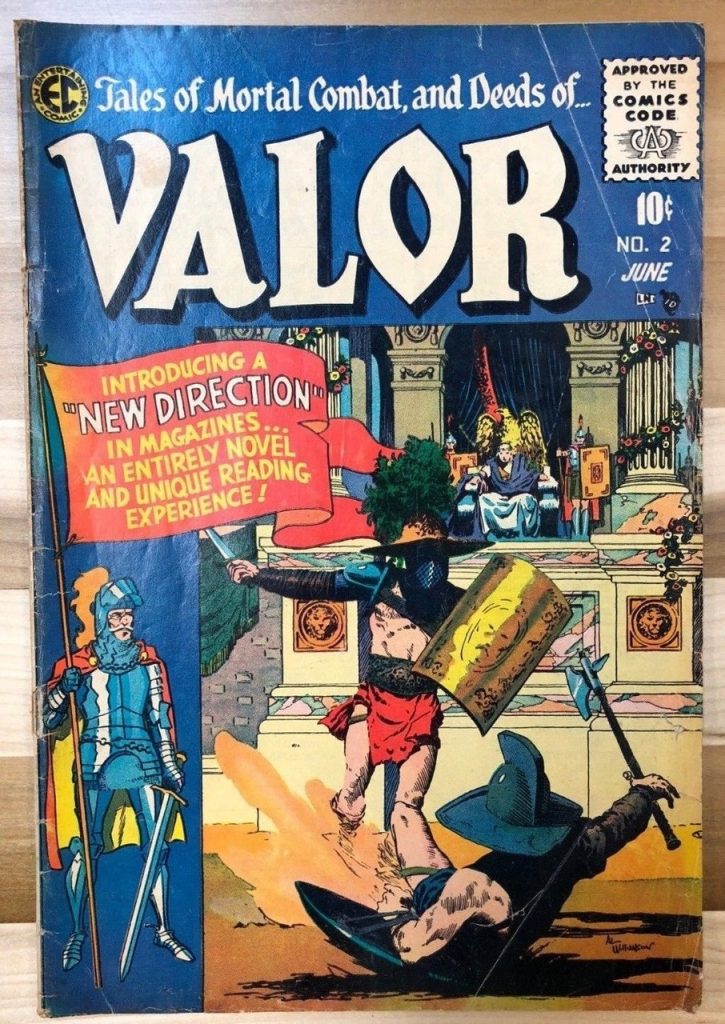

Regular EC artist Al Williamson and other members of “The Fleagle Gang” would often collaborate on stories for EC. Other members of “The Fleagle Gang” who contributed to EC books were Roy Krenkel, and Angelo Torres. If Gary Gygax first encountered these men’s work in the pages of EC Comics, he would later have also encountered them through the cover art of his favorite Appendix N books. Roy Krenkel’s prolific art would be found on the covers of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Lin Carter, and P. J. Farmer books. In sort of a homecoming, the 1965 book Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure features interior art by Frank Frazetta (six illustrations), Al Williamson and Reed Crandall (four illustrations), and another two illustrations by Reed Crandall alone. From the talented hands and minds of just these three EC artists, many an inspiration has been drawn. Perhaps Gary Gygax might also have seen Williamson’s work on Sunday strips of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan. (6) Too, it doesn’t seem too out of place to mention that George Lucas cites Al Williamson as one of his inspirations for Star Wars, specifically seeking the artist out to illustrate the Star Wars newspaper strip.

Also among EC’s roster of artists is Wallace Wood who could be found on covers for Manley Wade Wellman and L Sprague de Camp, including de Camp’s Conan work. “Ghastly” Graham Ingels, one of the more seasoned artists on EC’s line-up of talent rendered pulp covers that predated them all. His cover for the Spring 1944 Planet Stories features among others the writings of Appendix N alum Leigh Brackett. As Gary Gygax began the journey through fantastic literature, it’s feasible to believe that those artists introduced to him through EC Comics might have been life-long traveling companions throughout his long sojourn through genre fiction.

By the mid 1950’s, EC Comics had begun to expand the roster of titles beyond their regular formulas. Perhaps books like Valor and Piracy would have also caught the eye and imagination of young Gary Gygax. Of all the books being published by Gaines, Valor, with covers showcasing medieval knights and warriors in epic battle, castles and pyramids, seems closest to the worlds Gary would later co-create for the Dungeons and Dragons game. It is certainly a possibility, but certainly Gary would have found ample fantasy and imagination in any of EC’s titles.

When taken as a whole, it’s easy to see that Gary begins his Appendix N nods appropriately at the beginning of his life influences, starting with his father’s stories, moving on to comics books, movies and the like. In context, it seems right to assume that he’s talking about seeing the EC Comics early on. It would also be of interest no doubt to know which movies had the most impact. In that same era, from “1950” on, he would have had available to him opportunities to see the Ray Harryhausen movies like The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and 20 Million Miles to Earth. He would have been there for the popularity of the giant bug movies that proliferated on drive-in movie screens, and too the resurgence of gothic horror with the Hammer films. But yet again, it would be easy to digress.

While we have been looking hard at the influence of the EC Comics and their roster of artists and writers with all their ties to other Appendix N mentions, perhaps the greatest connection to Dungeons and Dragons and EC Comics is not the obvious attraction of the fantastical stories and the art, but perhaps the connecting tissue can be found on the letter pages themselves. Specifically, in the three consecutive issues of Tales from the Crypt #18, #19, and #20 (issues #18 and #19 still named The Crypt of Terror before being renamed to Tales from the Crypt by issue #20). On the letters pages of these three issues—named “The Crypt-Keeper’s Corner”— recommendations for further reading are suggested. It all begins in issue #18 when Guy Fulman from Lebanon, Ohio writes and asks the Crypt-Keeper where he might find “good books and short stories of this type?” The Crypt-Keeper (Al Feldstein as editor of the letters page) was happy to recommend books by Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Mary Shelly, naming different works by each author.

By issue #19, there was no need of an outside query for the Crypt-Keeper to volunteer the “Crypt-Keeper’s Literary Selections.” This small aside which ends the letters page offers, “The following is a further listing of my favorite fine mystery literature, which you can obtain at your local library! BRAM STOKER: Dracula, H.G. WELLS: The Invisible Man, RUDYARD KIPLING: The Phantom Rickshaw, and W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM: The Magician.”

The last time these recommendations appear is in issue #20 of Tales from the Crypt, ending the letters page with same heading, “Crypt-Keeper’s Literary Selections.” In this final list, the Crypt-Keeper recommends: “H.P. LOVECRAFT: Lurker at the Threshold, BORIS KARLOFF: And the Darkness Falls, and BRAM STOKER: The Mystery at Sea.”

All three of these issues, early in EC’s run of the new trend books, come in 1950, at the very beginning of Gary’s announced interest in genre fiction. Could it be that young Gary Gygax who began his imaginative journey through the stories found within these pages saw and filed away in the recesses of his own mind the idea of acknowledging and suggesting to like-minded folks further fantastic literature? Perhaps it is not only the imaginative storytelling at EC that left its mark on Gary Gygax, but the novel idea of an Appendix N at all?

The fact of the matter is that we may never know in what way “the long-gone EC ones” impacted Mr. Gygax. We only know that they did because he said that they did. We have probably spent more time thinking about it on these pages than he ever did in his working life. It is easy for us to acknowledge that we are all the sum of many different influences and that ascribing percentages or details would be hard for us to accomplish even in our own lives, much less that of someone who we can no longer ask. We do know that Gary enjoyed these comic books enough to mention them amongst a list of highly regarded and well-loved authors of literature. EC Comics are certainly in very good company here. Perhaps there is still an acquaintance of Gary’s out there who might have heard him mention those comic books, but it probably wouldn’t change much beyond what is already known. We already know all we need to know about EC Comics… great stories are capable of inspiring more great stories.

Footnotes:

- Statistics mentioned in “Foul Play: The Art and Artists of the Notorious 1950’s EC Comics”—Grant Geissman—2005, pg.11

- Tales of Terror—Fred von Bernewitz and Grant Geissman—2000 edition, pg. 77

- Tales of Terror—Grant Geissman—2000 edition, pg. 96

- The EC Fan Bulletin #1—1953—published by Bob Stewart

- The Ten-Cent Plague—David Hadju—2008, pg. 332

- The Art of Appendix N—Goodmans Games Gazette—Joseph Goodman