Comics in D&D

by James Maliszewski

After years of closer examination, I think it’s pretty widely known that Original Dungeons & Dragons artist, Greg Bell “borrowed” a lot of his illustrations from Marvel comics from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. While I understand that the practice of “swiping” (as it is known) is controversial in comics circles, I’m not much bothered by it in the case of Bell’s OD&D pieces, in part because it only further emphasizes just how amateurish the 1974 game and its initial supplements were. Rather than finding these swipes worthy of condemnation, I find them strangely charming.

Perhaps Bell’s most famous swipe is the “Fight On!” image that appears almost at the very end of The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, the third and final volume of OD&D.

Compare this illustration to this panel from issue #167 (April 1968) of Marvel’s Strange Tales, featuring Nick Fury, as drawn by Jim Steranko (above).

As we’ll see, this issue was the inspiration for quite a few illustrations that appear in Original Dungeons & Dragons and its early supplements. Take, for example, this barbarian who appears in Men & Magic.

Elsewhere in the aforementioned issue of Strange Tales, we find another panel featuring Nick Fury (above), whose pose is almost identical to that of the barbarian.

Strange Tales was an anthology comic that featured a variety of different characters and stories over the course of its seventeen-year existence. In its later years, its mainstays were Nick Fury and Doctor Strange. Unsurprisingly, panels from Doctor Strange also figure in Greg Bell’s artwork. The most obvious one is the box cover of the first through third printings of Dungeons & Dragons (which also served as the cover to Volume 1 in those same printings).

Issue #167 features a mounted Viking warrior (above) that looks nearly identical.

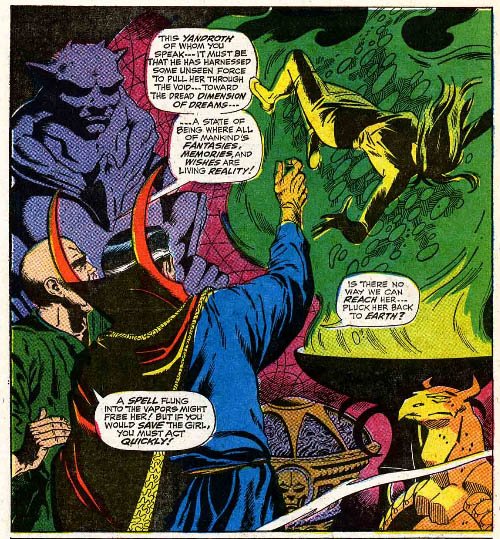

Early printings of Monsters & Treasure, the second volume of OD&D, includes the following piece of art, depicting a sorcerer in his lair:

Take a look at this panel from the Doctor Strange story (drawn by Dan Adkins, above) in the same issue of Strange Tales.

Interestingly, both of the pieces inspired by Doctor Strange were removed and replaced in later printings of OD&D. Why this happened is anyone’s guess at this point, but I think it unlikely that it was done because anyone at TSR was uncomfortable with Bell’s having swiped artwork. If that were the case, several other pieces would also have disappeared from subsequent printings.

Lest anyone think all the art swipes in OD&D came from a single issue of Strange Tales, there’s the case of Esteban Maroto’s Dax the Warrior. This fantasy series unfolded over about a dozen issues in the pages of Eerie magazine, beginning in 1972. Maroto, a Spaniard, worked extensively in the American comics industry for over a decade, starting in the early ‘70s. He is perhaps best known for his work on Vampirella and having created Red Sonja’s chainmail bikini for Savage Sword of Conan.

It is not at all surprising then that OD&D’s first supplement, Greyhawk, should feature an homage to Maroto. Here is Supplement I’s cover. Take note of the warrior on the left side facing off against a beholder.

Compare him to the warrior on the bottom left of these panels (above) from Maroto’s story Chess. The similarities are quite striking.

There is another swipe from Maroto in Blackmoor, featuring a magician, also from the story Chess. Here is the illustration from Supplement II:

The model for the magician can be seen in the middle bottom of this page by Maroto (above).

There are undoubtedly other examples of swipes in the early history of not just Dungeons & Dragons but other roleplaying games. To my mind, this is to be expected, since these initial publications were essentially the works of fans with limited resources. Greg Bell, for example, was a very young man at the time OD&D was being put together and it is not at all unusual for inexperienced artists to seek inspiration in the works of their elders. Moreover, D&D itself contains numerous swipes from literature and cinema, particularly when one looks closely at the monsters, treasures, and spells of the game. Bell’s illustrations are thus very much in keeping with the nature of the game in which they appeared and are another example of the curious alchemy that led to the success of Dungeons & Dragons.

Illustrations in this article are published with journalistic intentions. No challenge is intended to original copyright holders.