June 28th is the birthday of Philippe Druillet, and to celebrate his accomplishments we present this article on his life and work. And for more on classic fantasy and science fiction art and artists be sure to check out The Artists of Appendix N.

Nihilism in Detail: The Dark Visionary Artwork of Philippe Druillet

by Brad McDevitt

The term “visionary” gets thrown around a lot, so much that it has lost much of its meaning. This director is “visionary” because he refuses to use CGI; that musician is visionary because uses a kazoo instead of a bass guitar. A true visionary does something new that is not simply different for the sake of being different.

In the realm of film, Orson Welles created whole new languages by which to tell stories in classics like Citizen Kane and The Third Man. In literature, Edgar Allan Poe was considered a visionary because he achieved levels of terror in stories that had never been seen before, as well as creating an entirely new genre of fiction (the detective story). Like Poe, H.P. Lovecraft was considered a visionary for fusing hard science and horror in ways that had never been expressed before.

The comics industry has had its fair share of visionaries, from Seigel and Schuster fusing teenage power fantasies and the immigrant’s experience to create Superman to EC Comics’ Bernard Krigstein inventing entirely original ways to tell stories in comics format.

And then you have Philippe Druillet, an artist whose work was unmoored from any visual language before or since.

French by birth, Druilllet had always been a genre fan and began his career with an adaptation of Michael Moorcock’s seminal Elric of Melnibone, which he later re-tooled as the story of Yragaël, doomed and traitorous prince of Cymmorak.

Other important works include Urm the Mad, the even more doomed and deformed (like two-heads-level deformed) spawn of Yragaël, the space-faring adventures of Lone Sloane, the Salammbo trilogy, Nosferatu, the story of the last vampire on a long-dead Earth, and many more. In 1975, with fellow comics maestro Moebius, he started the magazine Metal Hurlant, more commonly known to English-speaking audiences, college students, and comics aficionados (not to mention stoners…) as Heavy Metal.

And in 1977, one of Druillet’s admirers asked him to do a painting based on the movie he had just directed. One can only assume that the portrait Druillet did of Darth Vader is still one of George Lucas’ prized possessions.

But what about Druillet’s art attracts such high-flight fans? In truth, his actual storytelling is somewhat lacking. The text of Yraegael is a nightmarish version of stream of consciousness, like reading James Joyce on about a dozen tabs of LSD. Urm is similar, with an even more nihilistic finale that entails the end of all life everywhere. The Lone Sloane adventures, all six of them, are more coherent and approachable, but are basically crazed standard Space Opera, like Han Solo on ‘shrooms.

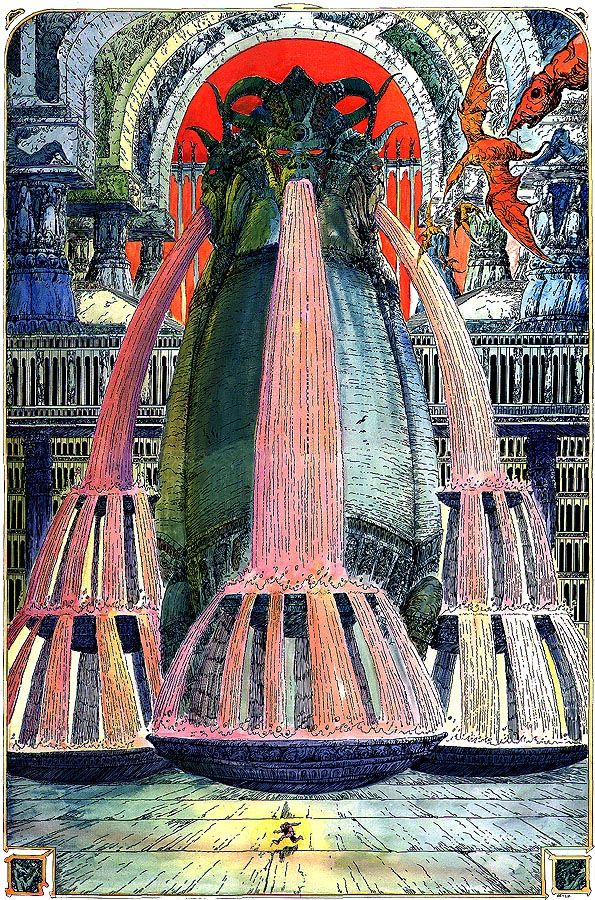

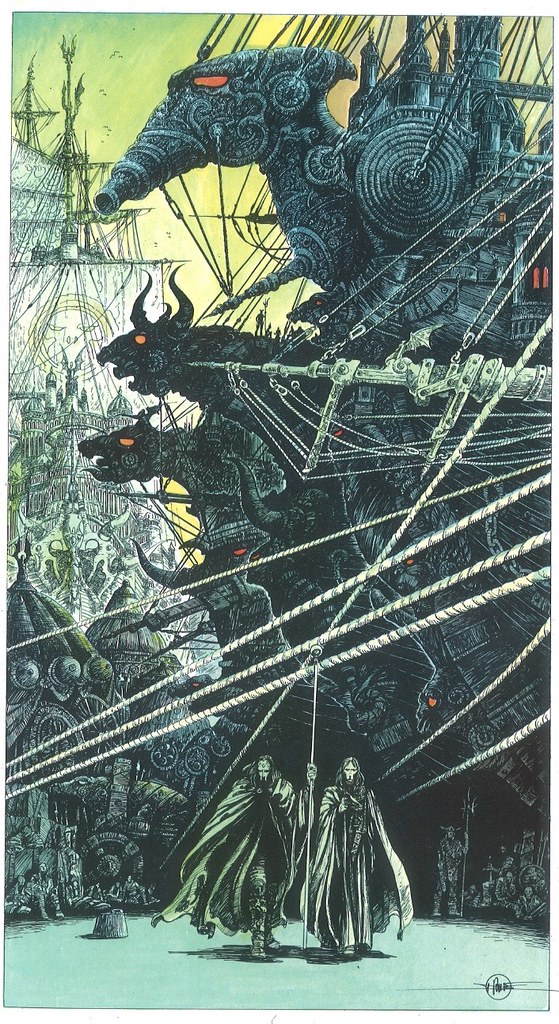

What makes Druillet so visionary is…well, his vision of the Universe. Detailed in ways well past the merely obsessive-compulsive, his art overflows with wildly decorated armor, weapons, spaceships, and more. In a Druillet illustration, everything is detailed and over-detailed to the point of being like a fractal painting; the more one studies one of his often full-page illustrations, the more is revealed.

Landscapes are not simply there to be walked through; his vistas include statuary that seems like a blasphemous version of the Buddha… only thousands of feet in height.

Other common imagery includes space-born stone platforms that dwarf the planets orbiting over them as misshapen gods play flutes and other instruments. To say that Druillet knows his H.P. Lovecraft is simply stating the blindingly obvious. In fact, 1978 saw Druillet sketch out several pages of the Necronomicon for Metal Hurlant, including a portrait of Lovecraft himself as a Deep One, one of the classic monsters of the Cthulhu Mythos.

But can Druillet’s vision be translated into a gaming experience? It is this author’s feeling that we can say “yes” to this, though with a few caveats. The sheer scale of Druillet’s world is incompatible with low fantasy; Conan the Barbarian or Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser would simply be dwarfed and lost in the beyond-gargantuan landscapes that Urm in particular moves about in, where city gates loom thousands of feet in height and background-detail fountains gush with amounts equal to small oceans.

Likewise, Druillet-inspired tales are best done in a short campaign, where the players know that their characters will almost definitely not survive. Think less along the lines of a continuing campaign and more a handful of epic stories that will affect the entire world or more, ala Moorcock’s Corum Jhaelen Irsei, though often with tragic endings or aftermaths.

In Druillet’s universe, the profit motive is barely present; characters have loftier or at least more cosmic goals: Yragaël seeks to reunite with the love of his life, even at the cost of the destruction of his homeland (he succeeds, but is cursed during the consummation of their love). Urm seeks to destroy the dark gods that have used him as a plaything (he fails and dies in agony when his companion, a small dragon, spits venom in his eye). Even the story of Lone Sloane, the most normal of his “heroes,” ends with him drinking himself to death. Few characters get a happy ending. In general gaming terms, such adventures would have the feel of an actual Lovecraft story, or at least a fantastical Call of Cthulhu adventure, without any comforting Sanity bonuses at the end.

A major aspect that judges can bring into play is the aforementioned crushing sense of scale. Castles are not simply small reinforced houses with an enclosed courtyard, they are megaliths with towers disappearing into the clouds and dominating the horizon. Idols and statuary are at the very least hundreds of feet in height and width, defying characters to hold onto any sense of their own importance, which handily brings us to…

Nihilism is the driving force of a Druillet-inspired adventure. A wise judge will discuss the parameters and potential finale of the campaign with her players beforehand, so that they understand that this will be a different and much darker series of adventures, with a definite and probably fatal end-point. Characters designed specifically to fit the campaign unto itself would be a very good idea, so that players are not bringing in characters to whom they have grown overly attached. Heroic or at least inevitable deaths are much easier to engage in with such short-term personas.

There is glory and satisfaction to be had playing in a Druillet-inspired world, but it is more the feeling of accomplishing something as your character dies. Gold, after all, is can be won and spent, but the goals of your characters in such a campaign are larger. Did you manage to kill the evil god, even at the cost of your own lives? In a Druillet universe, that prize would be considered worth the price.

For readers who have found this article intriguing, I have included some web links below. His works are easily and affordably found on Amazon or eBay; I personally would recommend the Dragon’s Dream reprints. Titan Books recently re-published a beautiful hardcover of his Elric graphic novel.

Dozens of Druillet’s individual illustrations can be found with a simple Google search, including some magnificent ones designed to be used as desktop backgrounds. Additionally, there are several places online to further study the work of this seminal master of fantastic illustration that has truly earned the title of “visionary.”

For more on classic fantasy and science fiction art and artists be sure to check out The Artists of Appendix N