Our Adventures in Fiction series is meant to take a look at the writers and creators behind the genre(s) that helped to forge not only our favorite hobby but our lives. We invite you to explore the entirety of the series on our Adventures In Fiction home page.

Adventures in Fiction: Fredric Brown

by Bill Ward

Anyone who has mined the treasures of Gary Gygax’s legendary Appendix N – his bibliography of fantastic and speculative fiction that served as inspirational reading in the creation of Dungeons & Dragons – discovers that it represents two kinds of authors. The first would be those like Jack Vance, Fritz Leiber, or Robert E Howard that so deeply shaped aspects of Gygax’s creation that even those who haven’t actually read those authors can still easily recognize some of the more common threads of influence. Then there are the other writers, writers who never put a broadsword in a barbarian’s hand, but who nonetheless featured in the imaginative landscape of Gygax even if one can’t draw a straight line from a story or concept of theirs to a particular aspect of D&D. Fredric Brown (1906-1972), prolific writer across genres who mastered everything from hardboiled mystery to science fiction short-shorts with O. Henry twist endings, is one such author.

Brown is still perhaps best known for his short fiction, particularly his short science fiction. A usefully appropriate comparison of his work to The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits conveys a sense of his interest in alternate universes, alien and supernatural encounters, odd speculations, apocalypses, and surprising twist reveals. But the comparison speaks, too, of Brown’s concision and absolute attention to craftsmanship – like a thirty minute episode of television, Brown’s stories are tightly written and cleanly and unambiguously structured, giving the impression of a writer who knows his story beat-for-beat before sitting down to write. Brown would reportedly mull over an idea for days, even going on long bus trips just to think through his plots and concepts – an autobiographical anecdote that supports a notion that soon becomes obvious when you read enough of his fiction – that Brown’s best stories were already finished in his mind before he rolled a fresh sheet of paper into his typewriter and put ideas to page.

And what stories! “The Waveries,” a slowly developing invasion of Earth by an alien ‘wavelength’ that removes electricity from the planet and permanently resets civilization; Russian nesting doll revelations of an alien ambassadorial mission to Arizona in “Puppet Show;” the madness of a space castaway for “Something Green;” the original creepy dollhouse story of “The Geezenstacks;” the time-travel fountain of youth of “Hall of Mirrors,” that demands only the loss of a lifetime’s lived experience; the solipsistic secret society speculations of “It Didn’t Happen;” the rebellion of the first true generation of humanity on Mars in “Keep Out;” an actual ‘reincarnated’ Napoleon Bonaparte in a mental institution in “Come and Go Mad;” the “Happy Ending” of the final days of an exiled space-dictator; the perils of relativity in “Vengeance Fleet;”“Knock,” in which the last man alive teaches his alien captors a thing or two about the Angel of Death and the nurturing of rattlesnakes; or the justly famous mano a xeno showdown to determine the future of two space faring civilizations (hint: the loser doesn’t have one), “Arena.” This last tale, first published in Astounding in 1944, is the story of a representative of the human race and his opposite number among the invading aliens known as the Outsiders, plucked from their spaceships by a powerful third party to fight it out in a battle of wits on a small planetoid, served as the inspiration* for the classic Star Trek episode of the same name in which Kirk squares off against the Gorn – though readers familiar with the TV show’s solution will be surprised by the resolution of the short story.

But Brown possibly makes an even bigger splash with his flash fiction – ultra short stories that turn on a dime, miniature paragons of wit and wonder, little puzzles of time travel paradoxes destroying the universe or unforeseen consequences re-doubling back upon themselves. Many of these hinge on the irony of a single last line, such as one astronaut’s accurate guess as to the probability of life on Mars as he waits for probe data (“Earthmen Bearing Gifts”/“Contact”), or the final line of “Sentry,” which flips the readers perspective when it describes the appearance of the hideous alien our protagonist just killed. In “Answer,” a tale resonant with today’s headlines of software learning and AI, Brown posits a great thinking machine as the product of the Space Operatic harnessing of the processing power of 96 billion planets, all connected together and laboring in concert. The first question asked of it: “Is there a God?” Its answer, as its relays fuse shut and a total universal control reverts to its mainframe: “Yes, now there is.”

Surely the author of so many ingenious wizard spells read “Rebound,” the short-short about a man who discovers he has the power to literally command others to ‘drop dead,’ only to hubristically shout his newfound Power Word: Kill somewhere with an echo; or drew inspiration from the impenetrable barrier of “The Dome,” perhaps enjoyed the Unseen Servant of “The Yehudi Principle,” or smiled at the humorous triptych “The Great Lost Discoveries,” which details how those making amazing discoveries such as invisibility, invulnerability, and immortality suffer horrible fates, like being blown off the surface of the planet or living forever in a coma. The element of wild power offering unforeseen consequences, particularly in the magic of D&D, and the underlying current of ironic black humor in how such things can backfire certainly can’t be credited to Brown – but, if you were undertaking the mental exercise of just how levitation might work in a windstorm or pulling out the legalistic stops to observe the literal commands of a Wish Spell, you could do worse than take notes from Brown.

Brown’s novels are no less polished than his short stories. For anyone that enjoys the era of film noir and hardboiled crime, with its mysteries and murders, its double crosses and femme fatales, Brown produced excellent thrillers, starting with The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947). With its teenaged protagonist and his touching story of loss and connection with a father figure, Clipjoint is as much or more a coming of age story as it is a mystery-thriller, something brown builds on in sequels. Brown’s crime thrillers may indeed be the strongest things he wrote, but it is probably his science fiction novels that best embody his combination of well-crafted plot, free imagination, and, at times, downright silly sense of humor.

Martians, Go Home (1955) is nothing if not silly. Earth, finding itself plagued by an invasion of insufferable rudeness in the form of smack-talking little green men from Mars, spirals into a farcical catastrophe while our novelist protagonist is driven out of his mind – an important point, since the entire debacle was a product of his mind in the first place. Playing with solipsism like this, the idea that the only certain, perhaps even defining, reality is one’s own, is a running theme throughout Brown’s work, and it lends an almost Philip K. Dickian intensity to perhaps his best science fiction book, What Mad Universe (1949).

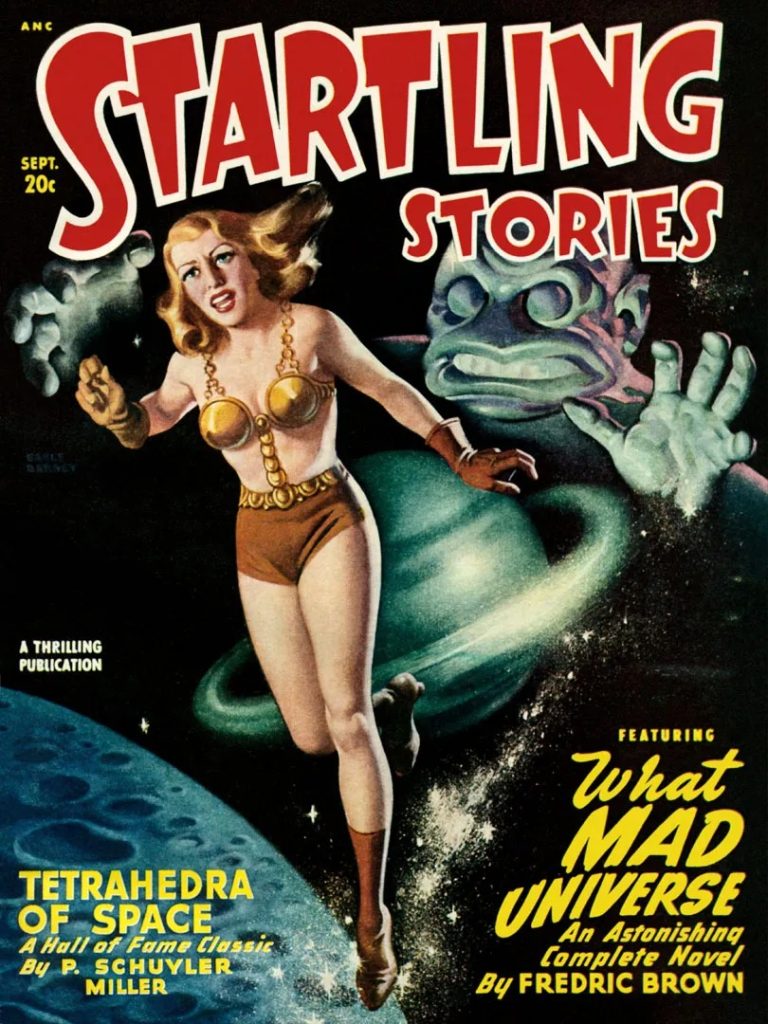

In What Mad Universe, Keith Winton, an editor at a science fiction magazine, finds himself transported into a parallel Earth in which many of the tropes he deals with in sci-fi stories are manifestly and bizarrely real. From amusingly satirical notions like it being perfectly normal for women astronauts to unironically dress like the pin-ups featured prominently on the covers of Planet Stories and Astounding, to rather terrifying implications of city-wide black outs (mistouts) every night across the globe that have everyone going home well-before sundown to lock themselves in against sinister gangs of Nighters, What Mad Universe compiles the mystery and weirdness of Winton’s ordeal as he runs from ruthless authorities that think he is an alien spy, meets his parallel universe self and sells him back some of his own short stories, takes a pocket reality drug that would fit right into a PKD novel, meets an artificial brain (a telepathic floating ball nicknamed ‘Meky’), steals a spaceship, and shares knowledge from his own world in an attempt to save this strange Earth in which Space Opera cliché is sober reality – and hopefully return home by the end of it all. From the attention-getting opening which has Winton slowly realizing something is off about his surroundings – that is, before a bug-eye alien walks into a small town diner and the ‘subtle’ differences between worlds become major ones – through the strange revelation of a world that is an appealing amalgam of satire and suspense, What Mad Universe is justifiably regarded as a classic work of science fiction, and it’s a compulsively readable one to boot.

And all of this just scratches the surface of an endlessly inventive craftsman operating freely across genres to tell fun, compelling fiction. Brown’s recurrent themes of perspective, possession, altered reality, and the ‘blowback’ of unintended consequences add an almost surreal edge to some of his work — even or especially when its clear that he has tongue firmly in cheek for a great many of them. But can picking up a Brown short or novel put you in touch with the origins of fantasy roleplaying in the same way that diving into Conan or Eric John Stark or Vance’s The Dying Earth would? No, the connection is a tenuous one at best, and I think that the reason Brown is listed in Appendix N is simply that Gygax read and enjoyed his work – and had the artistic awareness to understand that influence doesn’t always operate in a straight line, but is a totality of one’s likes and experiences.

*as well as, perhaps, the episode of The Outer Limits entitled “Fun and Games,” though Brown was uncredited.