It Was a Dark and Silly Night – A Look at John Bellairs’ The Face in the Frost

by Bill Ward

Whimsy and suspense don’t generally mesh all that well together, for they tend to swing toward opposite poles of reader engagement. Whimsy tickles the intellect, relying on novel juxtapositions and a great deal of textual playfulness – it’s cute, it’s precise, and most often it resides in a place of certainty and safety. Suspense – or more accurately in the case of John Bellairs’ 1969 debut novel The Face in the Frost, dread – is instead the assassin slipping past the intellect to knife that deepest part of the hind-brain, or perhaps its better to say its the cold, rhythmic pounding of subtle waves of suggestion that periodically climax in the massive erosive collapse of the shoreline of a reader’s composure. This horror effect absolutely requires a sort of visceral engagement with the material, a thorough Secondary Belief just like with fantasy – the kind of thing that jokey anachronisms, deliberate wordplay, and humorous allusions would seem to undermine at every turn. But Bellairs manages the trick of juggling these disparate elements with the sure confidence of a natural storyteller in a concise, captivating way that rarely places a foot wrong and never comes close to overstaying its welcome.

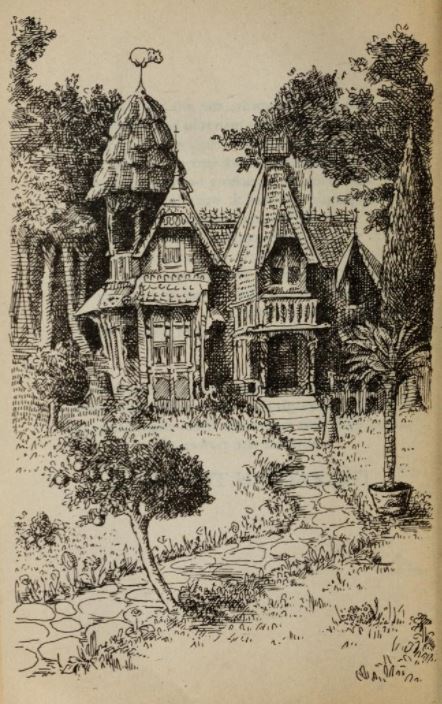

The Face in the Frost concerns the wizards Prospero – Bellairs cheekily informing us that no, he’s “not the one you were thinking of” — and his best friend Roger Bacon (whom Bellairs, with perhaps yet more cheek, never quite disqualifies from being the Wonderful Doctor himself!)* as they set out on a quest to confront a rival wizard, Melichus. The book begins with Prospero at home: “He lived in a huge, ridiculous, doodad-covered, trash-filled two-story horror of a house that stumbled, staggered, and dribbled right up to the edge of a great shadowy forest of elms and oaks and maples.” Already in this opening paragraph we see the whimsy seeded with a bit of darkness (the word ‘horror’ itself, though used in a different context, the “shadowy forest”), and it only snowballs in alternating and mutually-reinforcing waves from there. The house’s gutters are carved into “screaming bearded faces” and a riot of zoological carvings decorate the porch, its observatory is topped by an artichoke dome crowned by a dancing hippo weather vane — but that’s nothing compared to the chaotic grab-bag of furnishings, trinkets, equipment, and artifacts, magical or otherwise, within the house itself. Dog clocks that wag their tails and tiger-faced steamer trunks that bite back, a functional bassoon carved into Prospero’s bed frame, a Magic Mirror that watches late-night movies, forbidden books of lore and the sprawling “paraphernalia of the practicing wizard: alembics, spiraling copper coils, alcohol lamps – all burping, sputtering, and glurping as red, blue, purple, and green liquids boiled, dripped or just slurched uncertainly in their containers.” Heaps of curiosities and oddities playfully setting for us not only the scene and the tone, but serving as a strong initial characterization of Prospero himself. Our first real taste of him is through the contents of his house, as if we’re peeking through the random jumble of his overstuffed mind.

Of course, Prospero also has the “inevitable skull” on display to remind him of mortality – but it more often than not just reminds him to make a dental appointment. Death and silliness, large stakes and small, magic and mundane – from word one Bellairs is craftily building his layer cake of alternating tonalities until it’s impossible to tease out one flavor from the other.

Prospero, in his safe old house full of his long wizard’s lifetime of curios and comforts, isn’t doing so well when we meet him. He’s been having bad dreams, bad premonitions, and a bad moth problem. It’s not even safe to go down into his cellar to top up a mug of beer, since the last time he was there he was menaced by a sinister moving cloak.** Somehow it’s all related to the cold: the subtly unseasonable frost that creeps over the house and property, making patterns on Propero’s windowpane suggestive of uncomfortable things. Things such as the unreadable word that haunts his dreams, and the strangely familiar face of a rival long since thought dead…

The two old companions venture forth into the world of first the Southern, and then Northern, Kingdoms to unravel the puzzle confronting Prospero and, as they progress from one curious and unsettling incident to another the true, potentially world-destroying scale of their predicament becomes apparent. Bellairs plays an expert game hopping from one menace to another – a tiny troll barring the passage of our miniaturized heroes with a window screen, a sinister town of hollow spaces and hollow people, a black magic trap on the side of the road to catch the reflection of Prospero as he looks into a river, a dead mummified forest of trees and corpses just a fingertip’s touch away from crumbling into their component ash, or even the very non-magical threat of a warband of marauding soldiers that must be barred from crossing a bridge – and he shows yet another subtle strength in presenting and then resolving all of these many conflicts. Those who like their fantasy systematized, with the rules for how magic works explicated in certain terms, may find Bellairs’ insistence on keeping the reader a bit at arm’s length, a bit in the dark, not to their tastes. But the strange wizard logic necessary to navigate these perils isn’t arbitrary, it’s simply amplified in mysteriousness by Bellairs’ careful parceling of information and, especially in the context of the overall book, only further heightens not just the danger our heroes face, but the engagement of the curious reader eager to grasp at some of the underlying logic itself.

The Face in the Frost is an impressive balancing act between a lot of disparate and potential catastrophically-interactive elements. It is at once an extremely simple tale, told is a rather direct and very concise way – but at the same time it presents a suite of engrossing magical conflicts that tend to show a whole lot while perhaps seeming to tell very little. It is written with charm, and despite the dread and peril, it presents an innocence of tone that showcases the unassuming style Bellairs’ would parlay into a career writing for young adults. And, while The Face in the Frost wasn’t initially marketed as a Young Adult novel, it certainly fits the bill – but that doesn’t mean it should be overlooked by an adult audience. Overall, the real unifying force holding Bellairs’ tonally diverse elements together in effective harmony is its absolute sincerity. I think it’s this that Lin Carter saw or felt when he compared The Face in the Frost to The Lord of the Rings in Imaginary Worlds*** it is a secondary world of wonders that never stops believing in itself. In the case of Bellairs, even his most whimsical and quirky elements never violate suspension of disbelief (right up to time travel and various playful anachronisms), and they certainly never stoop to the deliberately ironic parody that infuses a great deal of lesser fantasy.

No such sins against literature from Bellairs, whose subtle and unassuming debut possesses an artistic humility that curbs any potential excess of style it could have easily slipped into, and does so to preserve the mystery and peril of dangerous, unknowable magic, and to give us characters to care about, rather than those which might serve as an archetype or even a punchline. I’ve deliberately left out many of the details of the plot of The Face in the Frost because it’s both extremely short and because it’s perhaps more important for a prospective reader to get a sense of the nature of the way the story is told, rather than be presented with a great many out-of-context details. In a day and age when much of modern media seems hellbent on popping every balloon of sincere engagement by meta-signaling and fourth-wall-breaking, or the resoundingly undermining thud of a ham-fisted quip delivered at the precisely wrong moment, it’s reassuring to see proof that humor and horror, suspense and silliness, can actually coexist in an entirely satisfying way. As a matter of fact, in the hands of someone like Bellairs, they can actually complement and reinforce one another; one might even say that that’s the central magic of The Face in the Frost, and Bellairs is the true Master Wizard at its heart.

* Bellairs’ Roger was unfortunately expelled from England for attempting to protect the island from viking depredations by surrounding it with a Wall of Brass. One minor error, however, resulted in an utterly ineffective Wall of Glass. “One of [the vikings] gave the wall a little tap with his ax, and it went tinkle, tinkle, and now there is a lot of broken glass on the beach. Not long after that, I was asked to leave.” Perhaps he waited for things to cool down, and ended up back in England a few centuries later.

** The origin of the Cloaker? Gary Gygax’s citation of The Face in the Frost in Appendix N makes it interesting to speculate upon what direct influences it may have had on Dungeons & Dragons. In addition to the nature of magic itself being of the ‘memorization’ kind that is most associated with the Vancian influence on D&D, and the occasional term that may have found it’s way from this book and into the game (bull’s-eye lanterns anyone?), I wonder if the biggest influence may just be in presenting two adventuring wizard characters who are flawed and intimately human – I for one can’t imagine the remote and majestic Gandalf (the White especially) as a Player Character, but these two crotchety, earthy, pragmatic (in wizard terms), and uncertain characters of Prospero and Roger Bacon would do just fine.

*** It seems odd at first to compare this very short novel of an episodic wizard quest to a half-million word epic, but I think Carter’s comparison makes sense in the context of publishing at the time. Certainly one point of similarity is that both works begin with the characters in a place of (relative, perhaps illusory) safety, only to tonally darken as they are thrust out into a world of unknown peril. The contrast between safety and peril serves to strengthen both elements.

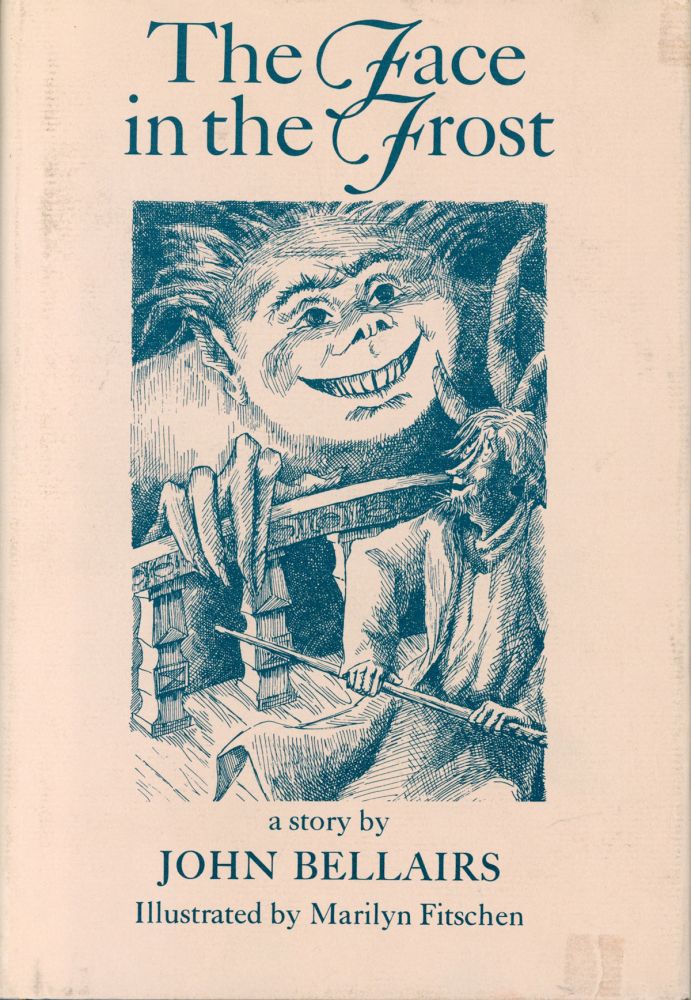

The header image (like the accompanying house illustration) is by the original illustrator of The Face in the Frost, Marilyn Fitschen, and was found at the John Bellairs online resource bellairsia.com.