Leigh Brackett, The Planetary Romantic

by Ryan Harvey

If you were a science-fiction reader in the 1940s, you knew there was one place to turn for a high quality, intelligent stories: Astounding Science Fiction. Under the editorship of John W. Campbell, Astounding was the spot for brainy speculative fiction. You didn’t look for that type of smarts over at Planet Stories, which was only interested in laser guns and trashy adventure flicks about muscular doofuses with slide rules and laser blasters who shot bug-eyed aliens. Or so the wisdom of the time declared.

But this wisdom was wrong, because starting in 1940, a writer named Leigh Brackett took up residency at Planet Stories. And what Leigh Brackett put out in each issue was some of the most influential and unusual SF of the era. Brackett was a groundbreaker, a woman in the almost exclusively masculine science-fiction field of the day who could craft tough heroes to compete with the most hard-boiled male authors. But she blended her planet-faring adventures in the Edgar Rice Burroughs mold with a sense of antique, wistful poetry found often in Weird Tales magazines. There was nobody like her then, and there may be imitators today—many unaware they absorbed her via Star Wars—but few equals.

Leigh Douglass Brackett was born in 1915 in Southern California. Her early influences were Douglas Fairbanks movies and the science-fantasy adventures of Edgar Rice Burroughs. She became lifelong friends with Ray Bradbury through the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, and married SF writer Edmond Hamilton in 1946. Her friendship with writer Henry Kuttner helped her refine her early stories until she started to make professional sales in 1939, igniting a long and varied career.

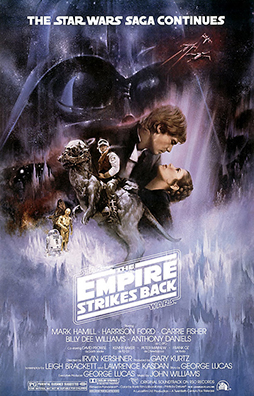

Along with her SF for the pulps, Brackett also wrote murder mysteries (No Good From a Corpse, An Eye for an Eye), Westerns (Follow the Free Wind), and was a successful film and television writer. After a helpful bookseller strategically slipped No Good From a Corpse into a pile of books sent to director Howard Hawks, Brackett formed an important relationship that lasted the rest of the famed director’s career. She wrote or co-wrote scripts for The Big Sleep (1946), Rio Bravo (1959), Hatari! (1962), El Dorado (1967), and Rio Lobo (1970). She adapted a second Raymond Chandler novel to film, The Long Goodbye (1973), this time for director Robert Altman. Her final work was the initial draft of The Empire Strikes Back, then known thrillingly as “Star Wars Sequel.” Although not much of Brackett’s draft made it to the screen, George Lucas dedicated the film to her in honor of her contribution to science-fiction adventure. Because, to put it simply, there is no Star Wars without Leigh Brackett’s work. There certainly wouldn’t be a Han Solo, a Leigh Brackett style character through-and-through.

Leigh Brackett is often called “The Queen of Space Opera.” This isn’t strictly accurate. Her science-fiction stories rarely feature galactic battles, laser shootouts, or jaunts between stars as in the defining space operas of E. E. “Doc” Smith. Her tales are often planet-bound on worlds fashioned as bitter frontiers. Merchants on hard times, gin-joint bartenders, hired killers, burnt-out mercenaries, and thieves of precious ores crossed the stage of her versions of Mars, Mercury, and Venus. Her heroes explored the ruins of dead civilizations and faced bizarre god-like beings and projected dreams from across time. This was the “planetary romance,” which owed much to Edgar Rice Burroughs and A. Merritt, but to which Brackett added dark poetry and shady protagonists. Her leading men were often broken, damaged, solitary—the signs of an author who could switch with ease to noir crime drama and knew how to write dialogue for Humphrey Bogart.

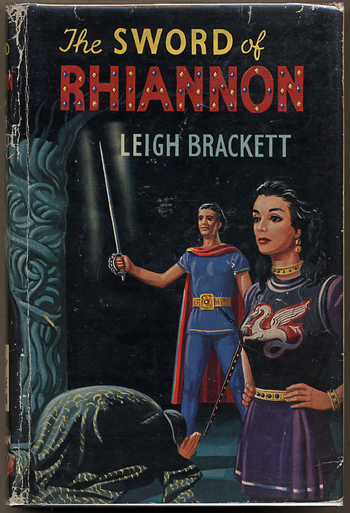

The “Leigh Brackett Solar System” was the backdrop for a series of superb planetary romances of the ‘40s and ‘50s, much of it published in Planet Stories: “The Moon That Vanished,” “ Shannach—The Last,” “The Last Days of Shandakor,” “Shadow Over Mars,” and “The Vanishing Venusians.” Three novellas featured her most famous hero, Eric John Stark, who seems a precursor to the tight-lipped and morally ambiguous movie heroes of the ‘70s. The three Stark stories—“Queen of the Martian Catacombs” (novelized as The Secret of Sinharat), “The Enchantress of Venus,” and “Black Amazon of Mars” (novelized as People of the Talisman)—show Brackett nearing the height of her powers. The actual height is the novel The Sword of Rhiannon (published in magazine form as “The Sea Kings of Mars”), one of the masterpieces of science fantasy. When later packaged with Robert E. Howard’s Conan novel The Hour of the Dragon as an Ace Double, it became a two-in-one knockout punch that must have transformed the minds of all younger readers who plucked it off the paperback spinner.

Hollywood and television work came and went, and Brackett always found herself drawn back to science fiction. One of her finest novels, The Long Tomorrow (1955), brought her to earth for one of the best post-apocalypse stories ever written. Near the end of her career, she returned to Eric John Stark and wrote a trio of novels that took him out of the solar system, where scientific discoveries had made lost civilizations obsolete. The “Skaith Trilogy”—The Ginger Star (1974), The Hounds of Skaith (1974), and The Reavers of Skaith (1976)—showed Brackett was as good as ever. It was not to last. She died of cancer in March 1978 at age sixty-two.

In 1976, writing an afterword to a collection of her stories edited by her husband, Leigh Brackett reflected on how she could keep moving away from the “fairy gold” of Hollywood and back to SF: “Aside from the pleasure of congenial work and the making of a living, science fiction has given me much that is beyond price: lifelong friends, a worldwide family, and a marriage that has lasted almost thirty years to date. Even fairy gold won’t buy all that!”