Our Appendix N Archeology and Adventures in Fiction series are meant to take a look at the writers and creators behind the genre(s) that helped to forge not only our favorite hobby but our lives. We invite you to explore the entirety of the series on our Adventures In Fiction home page.

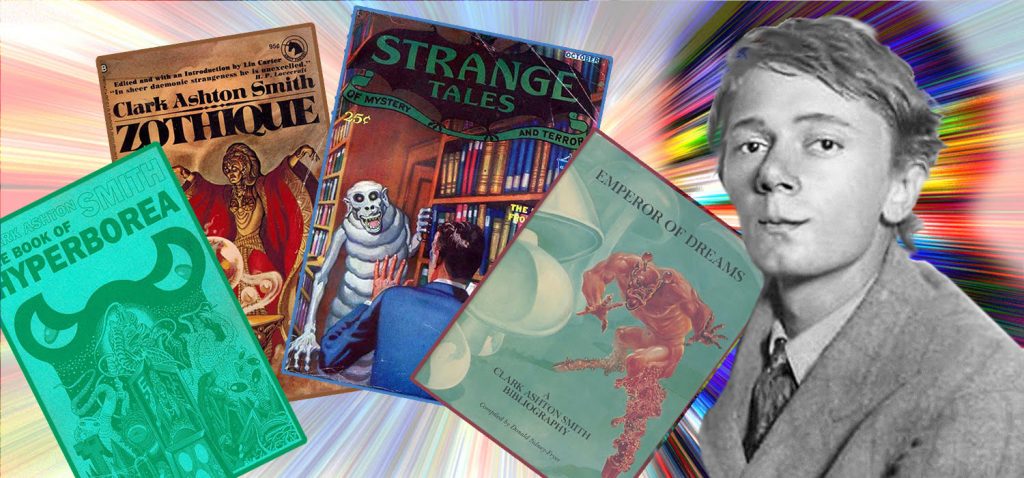

Appendix N Archaeology: Clark Ashton Smith

Gamers often point to Appendix N and decry the absence of a particular author (or three, or seven, or…), declaring Gygax’s omission of them to be a literary crime of some sort. Putting aside the unbelievable idea that gamers may complain about things for the moment, we must realize that Appendix N is not a list one can argue with. It is a catalogue of all the literary influences Gygax chose to recognize as wellsprings from which Dungeons & Dragons flowed. Since it is representative of one man’s work, we can’t claim he made the error of excluding a particular author, even if we believe we can see their influence in the final product. Game design, like art, is a subjective process and one tends to see what one is inclined to see.

While we cannot fault Gygax for not including certain names, we can, however, dig deeper into the authors he does list and examine where they drew their influences from. In the process, we discover that some of the names that people grumble about over their absence, are in fact representative in the works of those that are present. One of these influencers of the influencers is the third name from “the big three of Weird Tales”—Clark Ashton Smith.

Clark Ashton Smith is a name that has only recently begun to creep back into the consciousness of the fans of genre fiction. Despite his amazing productivity in such a short period—he wrote more than a hundred short stories in the “weird fiction” vein in only about five years—circumstance precluded him from enjoying the prolonged popularity and public recognition that his colleagues and constant correspondents Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard enjoyed.

Unlike Lovecraft, Smith lacked the cadre of devoted fans and writers dedicated to keeping his work in print or expanding on the concepts he created. And whereas Howard’s signature character of Conan the Cimmerian would captivate imaginations and be raised back into the public eye by the efforts of a devoted curator of his literary estate, Smith’s massive body of work focused more on creating unique worlds where stories unfolded rather than reoccurring characters who adventured there. By the time Smith’s work began to re-emerge thanks to the efforts of Lin Carter’s editorship of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series line of paperbacks (Carter edited four anthologies of Smith’s stories for that series between 1970 and 1973), the foundations of Gygax literary influences on Dungeons & Dragons were likely already set, their intellectual concrete cured. We can speculate this might be the reason for Smith’s absence from Appendix N.

Clark Ashton Smith was born in California on January 13, 1893 and would remain a lifelong resident of the Golden State. He spent the majority of his life in Auburn, California, dwelling in a small cabin his parents erected. Smith lacked a complete public education, finishing only eight years of grammar school before pursuing his education at home, largely self-taught. This lack of formal education wouldn’t hamper his literary career in the slightest, however.

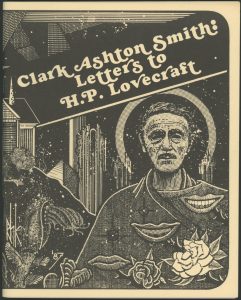

Smith attempted fiction writing in his youth, inspired by Poe and the Arabian Nights stories he read at home, but it wasn’t until he turned his attention to poetry that he began to flourish as a writer. Smith met and became friends and a protégé to George Sterling, the noted California poet who was at the forefront of a Romantic revival at the time. Sterling encouraged Smith and the young poet enjoyed critical success with his first volume of verse, The Star-Treader and Other Poems. In 1920, Smith compose the long blank verse poem The Hashish Eater, or the Apocalypse of Evil. The poem was read by H.P. Lovecraft who, in typical Lovecraftian epistolary proclivity, wrote the poet a fan letter. This missive began a correspondence that lasted until Lovecraft’s death.

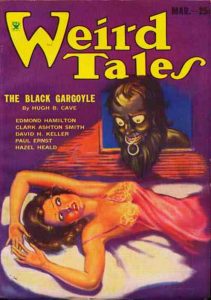

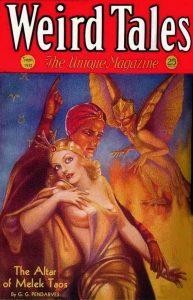

Smith might have gone on to world-wide renown as a poet had not economic forces intervened. In 1929, the stock market crashed, plunging the United States into the Great Depression. Smith, facing both widespread economic hardship and the need to support his aging and ailing parents, turned to fiction writing, a field only slightly more profitable than poetry. Many of these tales saw publication in the pulp magazine, Weird Tales, which introduced his work to Robert E. Howard. Soon, Smith and Howard were enjoying a correspondence as well. The “big three of Weird Tales” exchanged letters constantly between 1933 and 1936, their ideas influencing on another and finding fertile ground in each other’s imaginations. The god Tsathoggua, a creation of Smith’s, was borrowed by Lovecraft in the story “The Whisperer in Darkness,” for example, and he in turned included references to the high priest “Klarkash-Ton” in another story.

Smith’s work was distinct from his compatriots, however. Whereas Lovecraft’s work celebrated certain themes like cosmic horror and inhuman contamination and Howard was known for his memorable characters, Smith built worlds, weaving baroque word tapestries to describe places such as prehistoric Hyperborea, the far-flung realm of Zothique, a land at the end of Earth’s prolonged death rattle, or the fictional French province of medieval Averoigne. He set many of his tales in these realms, places J.R.R. Tolkien would later describe as “secondary worlds”—coherent imaginary lands that would be the predecessors of the campaign worlds gamers later become intimately familiar with.

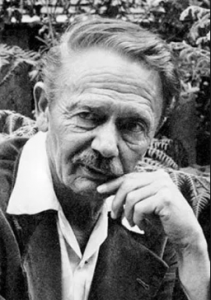

Smith’s weird fiction writing ceased almost as quickly as it began. The mid-1930s took a heavy toll on Smith. His mother died in 1935 and Robert E. Howard committed suicide in 1936, ending the exchange of letters between the Weird Tales’ triumvirate for good. Both Lovecraft and Smith’s father died in 1937, and with their passing, Smith’s literary fire cooled to embers. For the remainder of his life, Smith’s creative efforts were focused on poetry and the visual arts; he became an accomplished sculptor and artist. He died at the age of 68 on August 14, 1961, his ashes buried beneath a boulder not far from the small cabin his parents had built.

Smith’s roots in poetry are evident in his prose. He is a “writer’s writer,” one with a deft command of vocabulary and no hesitation to use it. He employs language to describe his imaginary worlds in a method that is more akin to prose poetry than to the lines of the average pulp writer. To appreciate Smith, you have to give yourself over entirely to the sorcery of his sentences, willingly submit to his evocations of language. His writings are works of dense beauty, which might also account for his lack of overall popularity among genre fans. Smith’s stories are not the blood and thunder of Howard’s, and, while Lovecraft demonstrates a love for antiquated word play, his use of old words and British spelling is far and away different from the language mastery that Smith commands.

Smith’s work inspired a number of authors working contemporaneously and subsequently to the “poet of Auburn’s” prolific period. In addition to his shared encouragements with Lovecraft and Howard, Smith’s writing has been credited as influential by such esteemed genre writers as Harlan Ellison (who despite being a fan once described Smith’s writing as “prose so purple it sloshes over into ultraviolet. A writing style that would make Hemingway break out in hives.”), Ray Bradbury, Jack Vance, Michael Moorcock, and Fritz Leiber (who not only paid a visit to Smith at his home but also incorporated the Weird Tales luminary into his novel, Our Lady of Darkness). Of the aforementioned authors, it’s Smith’s influence on Vance which leads us directly into the origins of Dungeons & Dragons.

Among Smith’s many literary worlds was that of Zothique. This setting for sixteen of his stories was the last inhabited continent on a far-future Earth. Zothique is, as Smith describes it, a world where “The science and machinery of our present civilization have long been forgotten, together with our present religions. But many gods are worshipped; and sorcery and demonism prevail again as in ancient days.” The Earth upon which Zothique lies is a weary one, and the Zothique cycle of stories are all in the Dying Earth genre. At least one writer and critic has claimed that Zothique owes its inspiration to William Hope Hodgson, another name from our Appendix N Archaeology, specifically Hodgson’s novel, The Night Lands.

Smith’s Zothique stories had a direct influence on Vance’s The Dying Earth tales, stories which likewise occur as Earth is fading and “sorcery and demonism” have returned. Without Smith’s creation, we might never have seen “The Eyes of the Overworld” and Vance’s other Dying Earth tales. And without those, we have no “Vancian magic” to serve as the basis from spellcasting in Dungeons & Dragons. Smith’s vision of a magical Earth at the end of time is therefore essential to the creation of the original fantasy role-playing game, regardless of whether Gygax was aware of Smith’s work or not. (As an aside, I’ll note that given Gary Gygax’s love of florid writing and his own occasionally purple prose, I find it surprising that Gygax never spoke more exuberantly about Smith in later years).

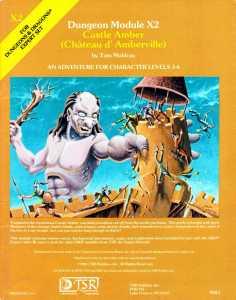

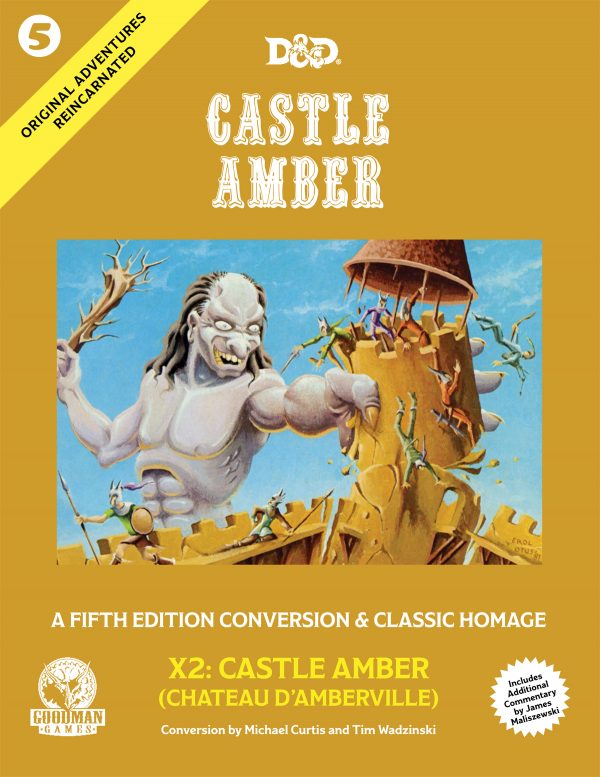

Of course, D&D fans from a long ways back are already aware of a more direct intersection between the role-playing game and the work of Clark Ashton Smith. This conflux of ideas owes its being to Tom Moldvay, a designer whose own list of inspirational authors is not only larger than Gygax’s (it can be found at the back of the Dungeons & Dragons Basic Rulebook edited by him in 1981), but specifically mentions Smith. Moldvay also wrote the adventure, X2: Castle Amber (Château d’Amberville), further linking the Weird Tales author and the game.

Castle Amber, despite what one might think, has no connections to the work of Roger Zelazny, but does owe a debt to Smith’s stories. The entire second half of the adventure is set in the realm of Averoigne, Smith’s fictional French province. The party must contend with antagonists ripped directly from the pages of Smith’s short stories (with permission of his literary estate), including “The Colossus of Ylourgne,” “The Beast of Averoigne,” and “The Enchantress of Sylaire.” This marks Castle Amber as one of the few early licensed adaptations of genre fiction into role-playing game material, putting it in good company with Fritz Leiber’s Nehwon, Robert Asprin’s city of Sanctuary, and Michael Moorcock’s Melniboné.

Castle Amber is a “funhouse” dungeon of the old school, filled with numerous oddities, anachronisms, and random events, and one’s opinion of it depends largely on the reader’s own attitudes regarding those things. However, regardless of whether an entire generation of role-players enjoyed the module or not, for many it was the first time they ever heard the name “Clark Ashton Smith.” Much as Deities & Demigods served to introduce gamers to the works of Fritz Leiber and Michael Moorcock, Castle Amber brought Smith’s name into the awareness of a new, albeit smaller audience—myself included. Returning to the adventure and rereading it after becoming familiar with the stories Moldvay incorporates into the module is a fun experience. It might even change opinions about X2 in some cases.

While Smith has enjoyed something of a resurgence over the past decade, partly due to Night Shade Book’s wonderful anthology series of all Smith’s weird fiction stories, it’s unlikely that he’ll ever gain the popularity of Lovecraft or Howard. His fellow Weird Tales colleagues are both more accessible to the average reader (Howard more so than Lovecraft) and both have benefited from adaptations of their work into other media forms, notably motion pictures which serve to introduce the authors’ concepts and characters to a non-literary audience. Smith’s work remains overlooked, which is a crime committed by popular culture on one hand, but which also makes those of us already familiar Clark Ashton Smith’s stories feel fortunate we know what others don’t. If you’ve never experienced Smith, consider this my invitation to join our close circle of privileged readers.