Where to Start with Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser

by Bill Ward

Aside from Conan the Cimmerian, there can be no more iconic image in all of sword-and-sorcery fiction than the dynamic duo of “the Twain.” Fafhrd, towering Northern barbarian, and Mouser, weaselly little thief, form a wonderfully visually complementary whole, and that’s even before you get to their actual personalities. Bawdy and reckless, bantering and adventurous, these two lovable rogues have traveled the length and breadth of a nowhere place called Nehwon, with many of their most memorable escapades taking place in the city of Lankhmar.

Leiber’s tales of “an earthier sort of fantasy” are a quintessential pillar of sword-and-sorcery fiction – indeed, it was Leiber that first coined that very phrase to describe the fantasy that emerged from the pulp world. But unlike Howard, whose writing life was brief and whose time spent writing Conan tales comprised just a few years, Leiber spun Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories over his entire career. Spanning four decades of material, the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales are varied in style, tone, and structure, as one might expect.

Both Howard’s Conan and Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories were assembled into a ‘series order;’ the various tales arranged according to a supposed narrative chronology, rather than in the order they were written. In the case of Conan, this was done after Howard’s death, and with the insertion of pastiche ‘filler.’ In the case of the Twain, this was done by Leiber himself, who not only arranged a series chronology but actively wrote pieces to “fill in the blanks” in the lives of his two heroes. Whether such an approach is a net good or bad for these respective series is subject to a lengthier debate than the purposes of this article – but in both cases, a new reader being aware of the inherent artificiality of the canonical ‘reading order’ is an important factor in approaching these series in a way that shows them in their best light.

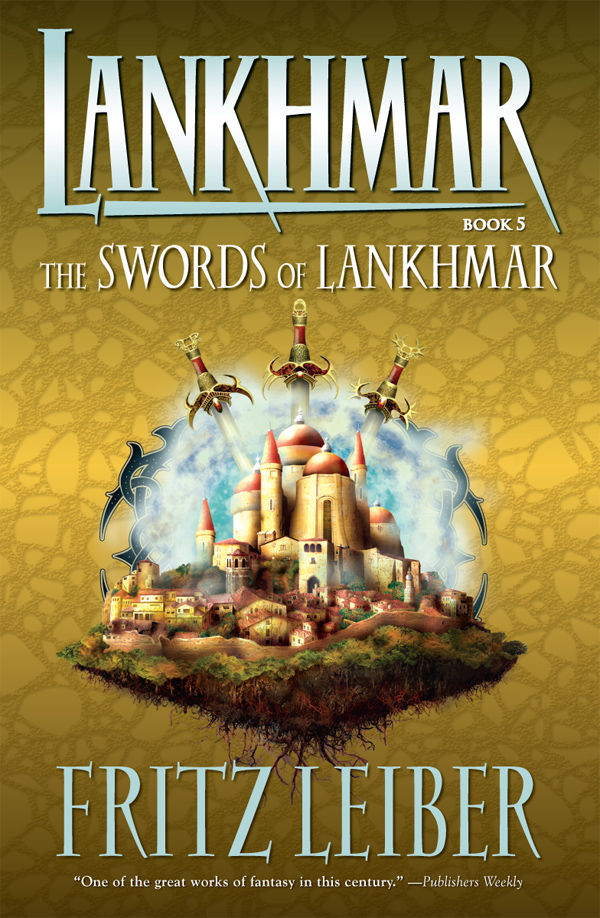

So where to start? Certainly, it’s entirely possible to pick up book one of seven of Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series and just read them all straight through. However there is, in fact, no reason why one should do so – these are not epic or high fantasy stories that outline one unfolding narrative. Furthermore, there are, in my opinion, good reasons why one should not approach the series in this way, particularly if the reader isn’t already invested in reading it in its entirety. My own recommendations would be to start with books two or three, or possibly with the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser novel, The Swords of Lankhmar, considered book five.

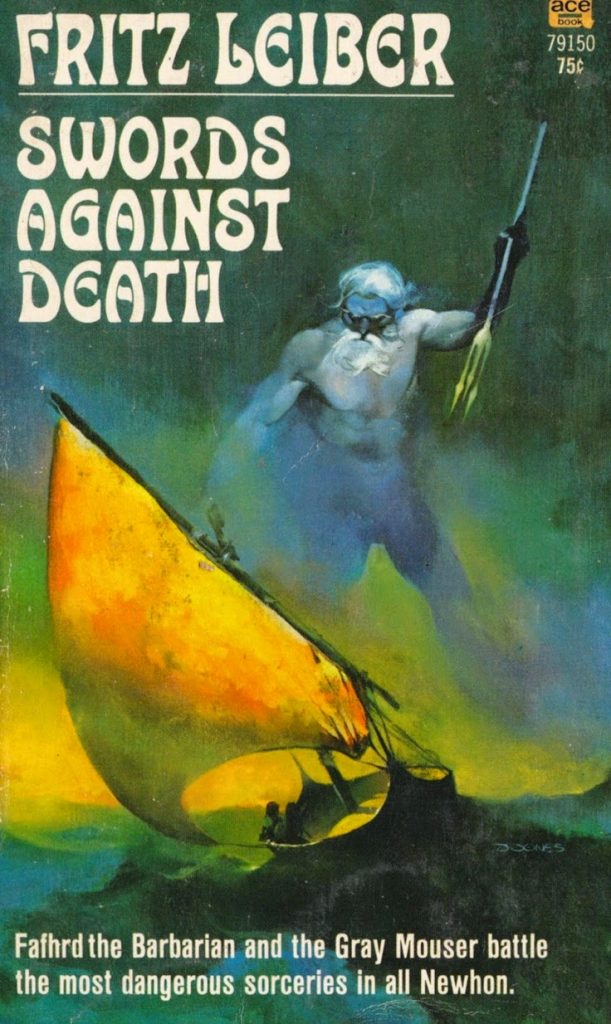

Swords Against Death, book two in the chronology, collects the earliest Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories and is a re-titling (and update) of their first collection, Two Sought Adventure. Both it and the next volume, Swords in the Mist, contain Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in the mode with which most fans associate their adventures. These are true sword-and-sorcery tales, fast-paced and lean tales of wild happenings and strange adventures, breezy, fun, standalone short stories originally intended for magazine publication. Standouts in Swords Against Death include “Thieves House,” “The Seven Black Priests,” and “Bazaar of the Bizarre,” as well as the first-ever published Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

The Swords of Lankhmar is a good place to start for readers that have a strong preference for novels over short fiction. Like the novella “The Lords of Quarmall” (Swords Against Wizardry), The Swords of Lankhmar was written in the sixties but expanded from earlier material. In the case of The Swords of Lankhmar, the first quarter of the book comprises the story “The Grain Ships,” but it has been updated and used as the jumping-off point for the larger events of the novel. For much of the rest of the story, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are undergoing separate adventures, only reuniting at the end to thwart a plot by Lankhmar’s rat population* to take over the city. Overall, it’s a great balance between the fast-paced drive and fertile invention of the early short stories and the more fully fleshed-out world one expects from a fantasy novel. As frustrating as it may be for our heroes to spend most of the action separated from one another (since they are so good as a team), it does serve to both quicken the pace, add dramatic tension, and allow the reader to experience a bit more of the bizarre world of Nehwon.

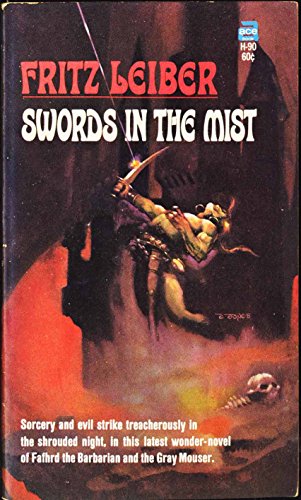

Swords in the Mist, book three, gives us “The Cloud of Hate,” “When the Sea-King’s Away,” and, possibly the greatest Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story ever written: “Lean Times in Lankhmar.” In my opinion, “Lean Times” is most enjoyable when the reader is already familiar with prior adventures of the Twain – it isn’t a case of needing earlier information to understand the piece, more of getting the most out of a story that is best appreciated when one is emotionally invested in these two characters. And if that applies in the case of this, one of Leiber’s finest tales, it applies even more especially when approaching some of his less strong – one could say more self-indulgent – stories.

“The Snow Women” is an ‘origin story’ novelette that kicks off Swords and Deviltry, book one of the narrative chronology. For readers ‘reading in order,’ this would be the first story they encounter – a story written 30 years after the first Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tale, and one written in a different style, with arguably a different aim. It’s also, to be blunt, rather boring in my opinion, though it does finish strong. Like the other two stories in this collection of ‘origin stories,’ it is best appreciated by readers who are already familiar with these characters. In “The Snow Women,” we are introduced to a young Fafhrd, and none of the contrast he presents with his later incarnation will be appreciated by someone for whom this is their first exposure to the character. Indeed, I think that all of the latter stories – which get increasingly self-referential – only make sense in the context in which they were written: as the latest story in a series of stories with which the reading audience is already intimately familiar. Approaching them fresh, decades after the fact, can easily lead new readers into forming mistaken impressions about the nature of the series as a whole.

Of the three novellas in Swords and Deviltry it is the final piece, “Ill-Met in Lankhmar,” that is the standout. Also a later story (1970 again), “Ill-Met” is still operating on the old paradigm of bantering and break-neck action, while incorporating some of Leiber’s later thematic concerns and stylistic flourishes. In this, and some other stories from the seventies such as those collected in Swords and Ice Magic, Leiber concerns himself with certain notions of psychological realism, almost (again, in my opinion) in an effort to justify the roguish, bachelor lifestyle of his heroes. This is something that needs no explanation and, perhaps most importantly, certainly not one rooted in the kind of arbitrary trauma of the ‘dead girlfriend’ variety. We readers already know why Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are as they are – because they are serial adventurers having serial adventures for our serial enjoyment.

And if one were to argue that this meta-textual justification for their behavior isn’t admissible in a literary context, then the critic has to point out that a great deal of later Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories rely on just these kinds of meta-textual conceits to even work as stories. From literal deities and Death Himself puppeteering events or persecuting our heroes (“The Sadness of the Executioner,” or the ‘Rime Isle’ sequence, both from Swords and Ice Magic), to jokey vignette stories like “Beauty and the Beasts” or “The Bait,” much of the sincerity of the early stories has been replaced in these later offerings by fourth wall breaking self-satire. While any and all of these stories still have merit, most especially for fans of what has come before and not least because Leiber’s wit and prose always have a way of shining through, they are neither the best of what the series has to offer nor do they make a very good starting point for a new reader.

Usually, these ‘Where to Start’ articles are about teasing out a confusing bibliography (such as Clark Ashton Smith’s), or simply recommending the best, most immediately accessible work of an author. In the case of Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, it was necessary for some literary criticism to peek through – because these tales, for all that they are consistent in many aspects, do vary greatly in execution and intention. That also means that this article relies more on my opinion – and mine is a strong preference for undiluted sword-and-sorcery, written in the spirit of the pulp era. But Leiber of course had his own artistic goals and preferences and, while I may be critical of the back half of the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser saga and its arrangement in ‘series order,’ that should not imply that there isn’t a great deal to enjoy in those latter stories or, even, that they may not well prove to be someone’s favorite. Our world, like Nehwon, is a big place, with room for giant swordsmen and shrimpy duelists, pulp enthusiasts and lovers of satirical fantasy.

*Fans of Warhammer Fantasy’s Skaven will immediately recognize the inspiration for the vile ratmen in the form of a vast undercity, a council of thirteen, and a ringing clock tower, as well as the notion of armed and armored bipedal ratmen.