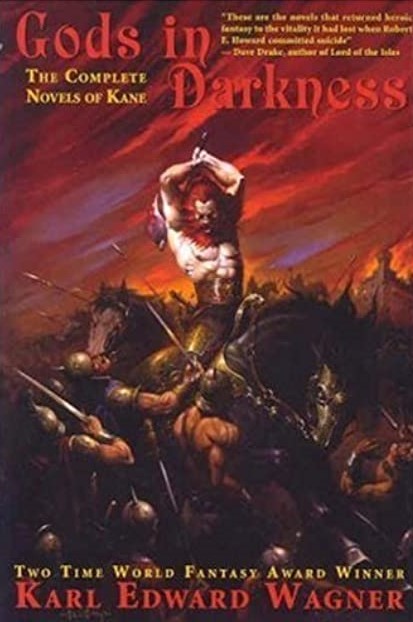

The Mad Dream Dies: Karl Edward Wagner’s Bloodstone

by Bill Ward

Aliens, lost civilizations, superscience vs. sorcery, perilous expeditions, a warrior maid, sentient crystalline entities, virgin sacrificing witches, bandits, ambushes, teleportation, a magic ring, cosmic visions, possession, a conjured tsunami, desperate battles, a jungle-shrouded city, cross and double-cross, devolved frogmen, a field tracheotomy, wall-leveling green lightning bolts, a world-threatening power, amphibian-crewed hydrofoils, lost tomes brimming with secret knowledge, a reconfigured semi-solid army of the elder dead, and an immortal juggernaut of a man at the lonely center of it all – it’s Bloodstone! Karl Edward Wagner’s everything-but-the-kitchen-sink gonzo romp through the grim old days of an earth that never was contains all of the essential ingredients of a healthy fantasy, along with everything else in the spice rack. And just like any highly-seasoned, oddly juxtaposed fusion cuisine, Bloodstone is not for the unadventurous palate; rather it’s a dish for those who don’t mind a dollop of sci-fi in their fantasy, a jolt of pungent prose in their sword-and-sorcery, and an extra-strong dose of amorality in their protagonist.

One could argue, and many have, over whether or not Kane – the scheming dark fantasy analog to the biblical Caine, god-cursed to an eternal life of bloodshed and woe – is actually a protagonist. Wagner himself disliked the term anti-hero for Kane, labeling his brutal genius as a straight-up Gothic villain, or even ‘villain-hero,’ but the sheer variety of Kane stories allows for a wide range of latitude for his role within them. In a short story like “Undertow” (Night Winds) for example, Kane is a black-hearted sorcerer keeping his lover ensnared with bonds of dark magic, whereas in others he seems little different from the ruthlessly expedient characters peopling much of modern fantasy, such as one might find in the works of George R.R. Martin, R. Scott Bakker, or Joe Abercrombie.

Regardless, there is something compelling in the character, at times almost sympathetic, and the inherent tragedy of his lonely doom is justification enough, if not for his actions, then for our fascination with his plight. The ultimate in masculine power fantasy – a deathless, brilliant, “three hundred pounds of bone, sinew, and muscle” loner that spends his immortal days completely on his own terms and is beholden to no one and no thing – is also existing in an endless living hell. Half of the trouble Kane gins up is simply an effort to relieve his own ennui, to manufacture some kind of purpose in the face of the bottomless nihilism that is the logical outgrowth of his condition – and, perhaps, the other half is the result of the reflexive hatred he generates in the rest of mankind. For Kane, cursed by his creator, is “doomed to wander eternally through the savage world of his making, driven by his curse, branded an outcast by the mark of death that lighted his eyes.”

Bloodstone begins with the chance discovery of a ring of untarnished metal, its face set with a single large bloodstone, a dark green gem shot through with veins of crimson. In the next chapter, the ring is the subject of a bandit squabble, as a criminal gang of marauders divides the loot of a recent ambush. It is here we are introduced to Kane, and he wants the ring:

“In the strained silence even the voices of the night creatures seemed hushed and distant. Kane’s eyes glowed with blue fire in the flickering light, cold death laughing derisively in their depths. Hechon had always felt a chill when he looked into those eyes, the eyes of a born killer. Uneasily he remembered the insane light that stirred in those eyes when Kane stood red with slaughter over those who fell before his blade in battle. Held next to his cheek in his left hand, the evil gleam of the bloodstone seemed to match Kane’s uncanny stare.”

Kane wins the ring in an explosive combat, the bandit chief’s blood spilling on the unholy object in an appropriate piece of thematic resonance. Kane bears the “mark of death” in his terrifying eyes, a warning to all mankind that here is not just a killer, but the killer, the uber-murderer, a being of pure violence – the literal progenitor of mankind’s strife. Not, notably, a being of malevolence, or inherent evil, but one in permanent opposition to his own kind nonetheless, in part no doubt because their lives mean nothing to him. For Kane is capable of decency, or the neutrality of indifference, and he is capable of affection – he even values others as a way to relieve his loneliness, or simply to fill the endless gulf of time that imprisons him. But, in the end, his doom will always overtake him, his indifference becomes callousness, his amusement, contempt, and his affection a possessive control.

From Bloodstone’s fast start Wagner proceeds faster still, hopping from one scene to another, leaving enough unsaid to tantalize the reader not only in regards to Kane’s new-hatched plan, but Kane’s own nature and the nature of the world itself. The first wildly strange thing we are treated to is Kane’s brief sojourn with an old lover, to consult ancient volumes left in her care – she being the be-winged, furred offspring of the priestess of a long-vanished prehuman race and the demonic god of her devotion. If at any point in the first few dozen pages the reader thought they were in a familiar fantasy world, Wagner now makes in abundantly clear that they aren’t in Kansas anymore.

Kane insinuates himself with Dribeck, the ruler of the nearest city-state in proximity to the vast, stinking swamplands of the Kranor-Rill: Kane’s ultimate destination. Dribeck backs Kane’s expedition into the fetid bog to find the ancient weapons rumored to still exist in the ruined, lost city of Arellarti – once home to a powerful elder race of reptilians, now slumped into decay and inhabited by their devolved descendants, the cold-blooded froglike Rillyti. Kane wasn’t lying when he said there was power to be found within the Kranor-Rill, but he has no intention of sharing it with Dribeck in his war with an aggressive neighboring city-state. Indeed, in the next short chapter hop, we learn that Kane is a spy for Dribeck’s rival, and soon it’s obvious that he is playing both sides for his own purposes, Red Harvest (or Yojimbo, or A Fistful of Dollars) – style. Except, of course, Kane isn’t interested in justice, or even survival – Kane wants to rule the world. Armed with the secrets of Bloodstone and an obedient army of amphibious brutes, he’s off to a good start.

Wagner performs a balancing act with Kane in Bloodstone – knowing as any good horror writer must that peril best takes root in the reader’s mind when it is hinted at, when the edges of the thing are skirted, when we see the effect through the eyes of those that are made to suffer. So Wagner pulls back a bit from his initial tight focus on Kane’s inner world, allowing Dribeck and Teres, the hot-blooded warrior daughter of the warlord of the rival city-state, to emerge as the proper protagonists of the book. So, even as we learn Kane’s ultimate strategy, we are removed from his immediate tactics, allowing for the audience to experience both surprise and dread. Kane, too, is not exactly his typical self as the story progresses – for there is an element of possession involved, of madness, as Kane merges minds with the true titular Bloodstone of the title. For it isn’t Kane’s ring – now fused irrevocably into the flesh of his hand — that the book is named for, but rather the enormous, sentient, and powerful globe of living bloodstone at the heart of Arellarti. It is a being with whom Kane enters a devil’s bargain, its own vampiric power slowly draining Kane’s vigor even as it grants him the means to wield incredible destructive force.

There is an element reminiscent of The Lord of the Rings* in Kane’s obsession with this particular ring of power: in one memorable scene, he abandons all sense of self-preservation while frantically raking for the lost ring in the muck and mire of the Kranor-Rill. Morally gray and rather conquest-minded on his own, it’s perhaps impossible to tease out exactly where Kane stops and Bloodstone starts, as their mad scheme of global (and, ultimately, cosmic) domination isn’t necessarily out of character for Kane. What is certain is that that which lies at the absolute heart of Kane, the eternal rebel, the eternal outcast, is a total refusal to be the tool of anything or anyone. It is this that ultimately redeems him – at least, in the context of this particular story.

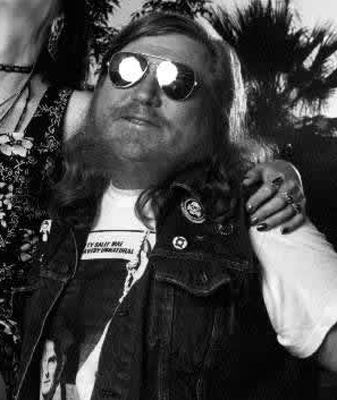

Bloodstone began as an idea Wagner had in High School, and it bears the hallmarks of youthful exuberance and wild pulpish abandon. It breaks all sorts of rules of structure and character, and it is full of endless surprises, both in terms of plot and prose. While it may have begun life as a teenager’s daydream, it was crafted by an older Wagner – while taking a break from pursuing a degree in Medicine — who had matured in his outlook and his craft. Wagner’s style is often dense, building to frenzied crescendos in the tremendous battles scenes and encounters with eldritch forces until it overwhelms with a crunchy effulgence. Some like to call it purple prose – to those critics I would say congratulations, you’ve managed to pinpoint the precise shade worn exclusively by Emperors and Kings.

There is enough meat in Bloodstone for a trilogy; instead, we get a wild, at times uneven, but wholly exhilarating standalone novel that says everything it has to and says it well. There are sustained flights of stream of consciousness and blood-and-thunder bombast, pulp indulgences, and explosions of frenzied invention. Bloodstone is as unapologetic as the ‘hero-villain’ at its core, bursting with the same kind of enthusiasm and authorial investment as the work of Robert E. Howard, and managing to be a true Dark Fantasy amalgam of horror and adventure without shading into the overwrought wallowing cynicism of the modern grimdark. In short, it’s a hell of a ride, and our particular misfit corner of literature has been immeasurably richer since a certain burly red-haired genius – and his burly red-haired creation – decided to turn the volume up to eleven and party awhile in the long shadow of Howard, Smith, and Lovecraft.

*for a deep dive into possible The Lord of the Rings influences in Bloodstone, be sure to have a look at “One Ring Rules Them All: A Comparison of Karl Edward Wagner’s Bloodstone and JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings” from our friend Brian Murphy over at DMR Books. Spoiler alert!