Clark Ashton Smith’s Hyperborea

by Bill Ward

“[I]n the harbour there towered an iceberg such as no vessel had yet sighted in all its sea-faring to the north, and no legend had told of among the dim Hyperborean isles. It filled the broad haven from shore to shore, and sheered up to a height immeasurable with piled escarpments and tiered precipices; and its pinnacles hung like towers in the zenith above the house of Evagh. It was higher than the dread mountain Achoravomas, which belches rivers of flame and liquid stone that pour unquenched through Tscho Vulpanomi to the austral main. It was steeper than the mountain Yarak, which marks the site of the boreal pole; and from it there fell a wan glittering on sea and land. Deathly and terrible was the glittering, and Evagh knew that this was the light he had beheld in the darkness.”

~ Clark Ashton Smith, “The Coming of the White Worm”

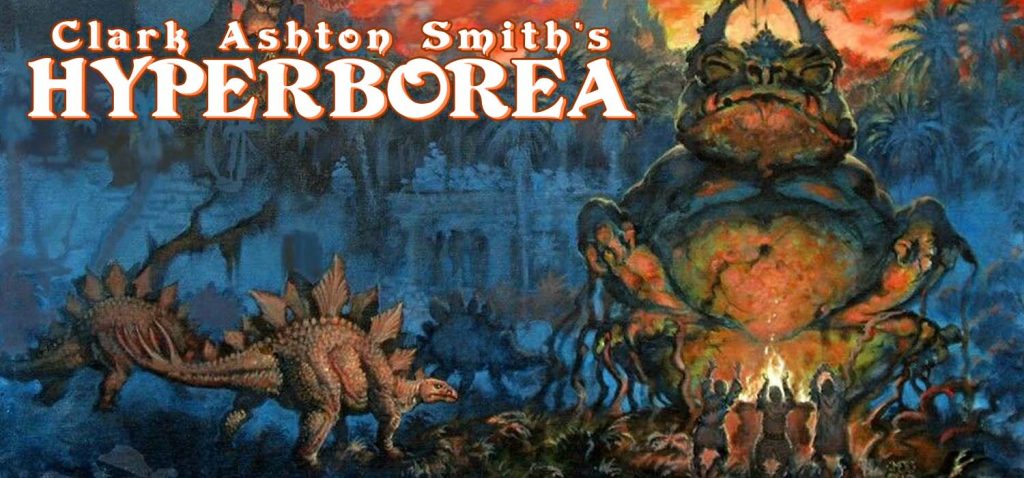

Hyperborea; ice-girded continent ‘beyond the northern winds’ where Paleozoic fauna stalk the jungle-shrouded flanks of ancient volcanoes, and grotesque elder gods slumber deep beneath the earth, indifferent to the frozen doom that creeps inexorably over the surface world. A perfect setting for Clark Ashton Smith’s blend of exotic imagery and lushly poetic prose, a land of strange sorcerous possibility rendered futile in the shadow of encroaching glacial annihilation. Smith’s Hyperborean story cycle of ten tales is one of his major works, both in terms of its enduring quality and in light of his own evolution as a storyteller.

Smith’s first step into the world of Hyperborea, 1931’s “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros,” introduces both the setting (we learn that former principle city of Hyperborea now lays abandoned) and is the origin of he who would become Hyperborea’s most famous denizen, Tsathoggua, a bloated extra-terrestrial amphibian elder god who lurks deep underground. This major contribution to the Cthulhu Mythos was by no means Smith’s (the great ‘Klarkash-Ton’) only one, but it is the one most associated with his name. But as Smith himself would say in regards to these stories specifically: “My Hyperborean tales, it seems to me, with their primordial, prehuman and sometimes premundane background and figures, are the closest to the Cthulhu Mythos, but most of them are written in a vein of grotesque humor that differentiates them vastly.”

Satampra Zeiros himself is a rogue, a character that would fit in alongside Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser or Conan much more so than many other typical Smith protagonists that come in the form of arrogant princelings, otherworldly magicians, or lovesick poets. Indeed the story itself, told in first person and telling of a botched temple-robbing expedition, skews much closer to the Howardian school of sword-and-sorcery than the usual dark elegies and stories dense with prose poetry that are a Smith trademark. The vein of dark humor found in “Satampra Zeiros” isn’t common to all of the other stories in the cycle, but it is to many, including the tale’s eventual sequel, “The Theft of the Thirty Nine Girdles,” which was written late in Smith’s career and published in 1958.

Hyperborea is, of course, a legendary northern realm “behind the north wind” first spoken of by the Ancient Greeks, a never-never place beyond the edge of the civilized map where impossible cities and peoples dwell in a pocket of warmth betwixt walls of killing cold. Smith’s Hyperborea draws much less on myth than it does on his own imagination, but the core elements of fabulous lost civilizations, bizarre animals, and perilous glaciation run through nearly every tale. Some stories, like the short comeuppance narrative of “The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan” or the wonderfully ridiculous magic door journey of “The Door to Saturn,” could have been written to suit any of Smith’s story cycles. But the majority of Hyperborean stories are as inextricably bound to this setting as any in Smith’s oeuvre, and the best of them utterly define it.

“The Coming of the White Worm” (1941) is one of those stories. Offering some of Smith’s most challenging prose, the story moves with the same stately, crushingly inexorable forward progress as the malign iceberg at its heart. The titular White Worm of the tale, a vile, pulsating thing oozing blood from empty eye sockets and commanding powerful sorcery, has as its goal the complete frozen destruction of the continent, and it has kidnapped some of the more powerful magicians of the age to assist it – and keep it fed. Adding an element of malignancy and agency to the freezing over of the world that Smith would revisit multiple times in his cycle (“The White Sybil,” “The Ice-Demon”), and told without humor or even much irony, “The Coming of the White Worm” is the icy-dark heart of the Hyperborean cycle.

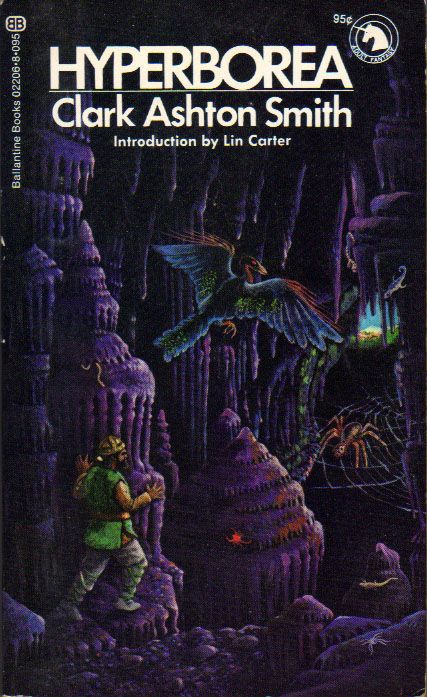

Somewhere between the farce of “Satampra Zeiros” and the frozen nightmare of “White Worm” is “The Seven Geases” (1934). Lin Carter chose this to start his collected Hyperborean tales for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series because he believed it to be the earliest story to occur chronologically of the ten – he might have just as well selected it because it’s a fantastic introduction to the world, giving not only a glimpse of many elements of the setting, but a taste of the tonal variations that permeate it. The story of a venal lord who is cursed to move ever deeper through an underground catacomb full of old gods, lost races, weird monsters, and assorted other grotesqueries, “The Seven Geases” presents an imaginative litany of odd events and personalities that uses mankind’s own startling insignificance as the punchline.

In “Ubbo-Stathla” Smith sets the story in the contemporary world of the 1930s – only to have the protagonist psychically regress back through the infinite corridors of time until he witnesses not only lost Hyperborea, but the amorphous, animate slime that dominates the world at the beginning of time. The first person “The Testament of Athammaus” tells how the great city of Commorium, described as a deserted ruin in “Satampra Zeiros,” came to be abandoned by its people. Written by the King’s headsman, “Athammaus” unfolds an incident equal parts surreal and horrifying, as an executed criminal refuses to stay dead for long.

The ten tales comprising Smith’s Hyperborea are a varied contrast with his other more consistently-themed story cycles, such as Zothique or Averoigne. More than in those other series, Smith’s development of the themes and concepts of his setting are more readily apparent in Hyperborea, and the sheer variety in the types of tales encompassed by the Hyperborean cycle make for a great showcase of Smith’s storycraft. Like the baroque lands of the magical future Zothique, doomed Atlantis, Gothic Averoigne, and the many lost planets and fabled pasts visited by this poet of the Weird, Hyperborea, ice-girt land of wonders, bears the indelible stamp of Clark Ashton Smith’s darkly imagined word-soaked dreaming.