Short Sorcery: C.L. Moore’s “Hellsgarde”

by Bill Ward

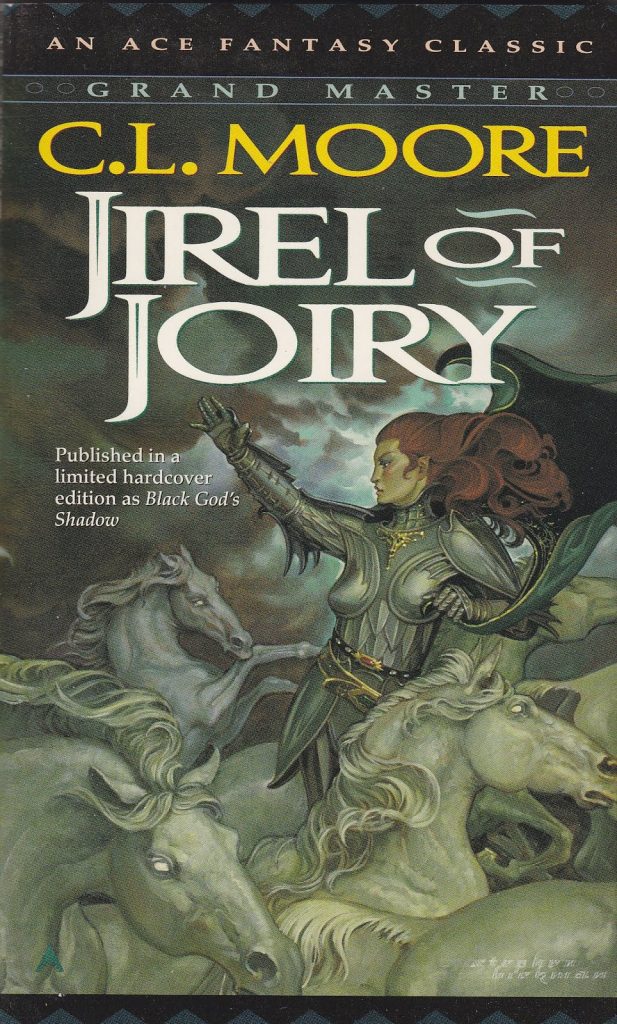

C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry is the kind of character a writer can build a series of stories around, sharply defined in ways that make her both immediately compelling and comprehensible to an audience, but with enough nuance to not only keep a reader engaged, but to ground the character in believability. And believing in Jirel – a flame-haired Medieval Lady with a temper as fiery as her mane, a woman desired and opposed by warlords, warlocks, and even spirits of the dead – is absolutely crucial for Moore’s enchanting tales to work as well as they do time and again, for the stories of Jirel are something akin to entering a waking dream of darkness. A dream in which the only reality or point of reference is Jirel herself.

Sword-and-sorcery is perhaps most simply defined as adventure fiction with a weird or horrific element. You might get the idea that Conan was tromping through a skewed version of antiquity until the giant snakes, animate iron statues, and Elder Gods show up. Much of the tradition of sword-and-sorcery follows this basic formula of a grounded, ‘low fantasy’ world into which a stark element of wrongness, a vivid splash of the weird, emerges to oppose the protagonist. The Jirel of Joiry stories both uphold and invert this approach, as in every one of them it is Jirel herself that is thrust into an otherworldly realm of magic and peril.

For contemporary readers discovering Jirel in books that collect her half-dozen tales together, this formula can start to feel formulaic. A parallel can be found when a modern audience binge-watches an episodic television show of the past, only to discover the repetition of stock plots, themes, and characters. Some things simply aren’t meant to be consumed in one greedy gulp, and story elements modern consumers of entertainment today might view as a weakness, are perhaps more an artifact of the intended venue for a story than some limitation of the authors’. For lesser talents than Moore, this repetition might prove a barrier to contemporary enjoyment. But at the time in which these stories were written, the formula itself was the signature of the character, and if it stands out more than other, perhaps more subtle formulae, that’s because it’s so big and boldly drawn it becomes the central point of everything in the story. The journey into the unreal is as much a part of Jirel as her striking beauty and unbreakable will.

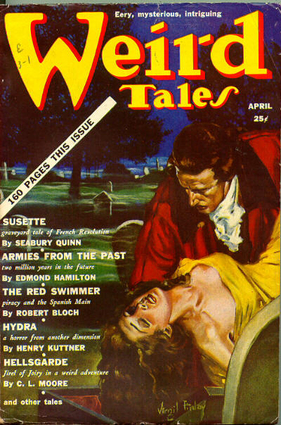

“Hellsgarde,” the final Jirel tale, departs from the formula in the most literal sense – though Jirel is still thrust into an inexplicably sinister environment and even leaves her own body at one point – and it is also perhaps a suggestion of how the series might have evolved had Moore continued with the character. One could also make the case that, rather than a sword-and-sorcery tale with horrific elements, “Hellsgarde” is a horror story with sword-and-sorcery trappings. Jirel is once again challenged by a devilishly handsome yet ruthlessly vile rival in the form of Guy of Garlot, and she has to dare a haunted castle – the Hellsgarde of the title – to find a mysterious treasure to save the lives of her captured leigemen.

In one of the frequent asides that make the character as knowable, distinctive, and, to my mind at least, darkly amusing as she is, Jirel reflects that these hostage men-at-arms “were hers to bully and threaten and command, but they were hers to die for too, if need be.” We the audience are often privy to her thoughts, both her fears and her hates – she frequently consoles herself by imagining smashing Guy of Garlot’s teeth out – and this interior monologue is a necessary window into these tales that are primarily experiential. Jirel’s adventures in other realms are at their heart about her emotional processing of the incomprehensible environments and situations she confronts – and her triumphs aren’t about having the strongest swordarm, but the strongest will.

Hellsgarde, cursed pile, was once the seat of Andred – a Lord whose mysterious, secret treasure was the envy of every power in the land. His impenetrable castle was taken in a siege, and he himself tortured for his secret. But he would not share its hiding place, and so Andred was slain, his dismembered body strewn through the surrounding swamplands and his castle abandoned to slump into ruin. In the two hundred years since, the haunted reputation of the castle has grown, but none who have braved it in search of Andred’s treasure have ever returned to share their tale. It is to Hellsgarde that Jirel rides, her impossible quest for Guy one of iron duty and, perhaps most importantly, damaged pride. Jirel is as jealous of her prerogatives as any Caesar, and as single-mindedly ruthless when crossed.

And while Hellsgarde might ostensibly be a part of our world, the sense of unreality and dread as Jirel rides up to it is every bit as otherworldly as her first journey into the mouth of hell in “Black God’s Kiss.” The fortress can only be found at dusk. A long causeway over the surrounding fens further separates it from the mundane world of our experience. Soon Jirel discovers this is no long-deserted ruin, as lining the causeway on either side are the freshly impaled bodies of dozens upon dozens of men:

“Jirel sat frozen. It was a nightmare. Only in nightmares could such things happen. This unbearable silence in the dying sunset, no breeze, no motion, no sound. Not even a ripple upon the mirroring waters lying so widely around her below the causeway, light draining from their surfaces. Sky and water were paling as if all life receded from about her, leaving only Jirel on her trembling horse facing the dead men and the dead castle… She could not bear it, and yet—and yet if something did not break the spell soon the screams gathering in her throat would burst past her lips and she knew she would never stop screaming.”

Moore is a deft hand at the poetry of suspense, and rarely shades into Lovecraftian histrionics even in moments of the most heightened weirdness. This is the threshold moment in the story, more subtle than crossing through a gate into another dimension or having her soul ripped from her body in death, but a journey from our world to a different one just the same. The castle, it seems, has recently been reoccupied by the descendants of Andred, and Jirel is invited to stay the night. What follows is the classic set up of the traveler entering the abode of evil, a hospitality trap as familiar to the Ancient Greeks as to the modern fan of jump-scare cinema, and Moore’s spin on it is as riveting as the best the horror genre has to offer.

“It was cold here, damp with the breath of the swamps outside, dark with two centuries of ugly legend and the terrible tradition of murder.” The freak show cast of characters that welcome Jirel are “pleasantly at home” in this decrepit ruin, their appearance subtly wrong in a way she can’t articulate, their bearing psychopathic. This is the court of Alaric, descendant of long-dead Andred, freshly reinstalled in his ancestral home. His servants seem barely human, his family a collection of Poe grotesques. Jirel, outward brazenness masking inner doubts, asks herself if these people can possibly be real. Even their dogs behave wrongly, and their children have the faces of devils.

Of course, things soon come to a head, Alaric and company are there to summon the disembodied Andred, and Jirel herself has been serendipitously provided as the perfect bait – for the spirit of Andred senses within her a “kindred fierceness” that blazes as hot as his own, even after two hundred years of death. Andred’s desire for her is a carnal one – the scene in which the invisible, yet still dismembered ghost forces an unwanted kiss upon her and drags her across the room is a vivid sharp smack punctuating the steadily rising suspense. And Jirel, having been subjected to that horror once, returns again to confront the ghost as she knows it is the only way to recover the secret of his treasure. There is a twist to the tale that demonstrates that Alaric and company are something more imaginative and strange than the reader may have at first guessed, and Jirel herself emerges with the mysterious treasure that will fulfill her bargain with the hated Guy – and also destroy him; just as Jirel once brought a deadly kiss back from another hellscape to slay one who would call himself her master.