Sifting Through a Sword-and-Sorcery Definition

by Brian Murphy

When Michael Moorcock asked readers in the May 1961 issue of Amra to “put a tag” on the style of fantasy he was writing with his Elric stories, he cast a wide net, letting it drag through a sea of stories that readers today would likely consider heroic fantasy, high fantasy, or sword-and-sorcery—or all of the above:

We have two tags, really — SF and “Fantasy” — but I feel that we should have another general name to include the sub-genre of books which deal with Middle Earths and lands and worlds based on this planet, world which exist only in some author’s vivid imagination. In this sub-genre I would classify books like “The Worm Ouroboros,” “Jurgen,” “The Lord of the Rings,” “The Once and Future King,” the Grey Mouser/Fafhrd series, the Conan series, “The Broken Sword,” “Well of the Unicorn,” etc., usw.

But, in the same essay Moorcock began refining these broad parameters, focusing on a subset of fantasy stories “which could hardly be classified as SF, and they are stories of high adventure, generally featuring a central hero very easy to identify oneself with …. tales told for the tale’s sake… rooted in legendry, classic romance, mythology, folklore, and dubious ancient works of “History.” These were quest stories, Moorcock added, in which the hero is thwarted by villains but against all odds does what the reader expects of him. He chose to exclude “alternate space-time continuum” stories, like Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee at the Court of King Arthur, on the grounds that they lacked sufficient seriousness. In short, he was working out the parameters of a yet-to-be named subgenre. While he advocated for the term “epic fantasy,” nevertheless he was speaking of a nascent form of S&S:

So, all in all, I would say that Epic Fantasy is about the best name for the sub-genre, considering its general form and roots. Obviously, Epic Fantasy includes the Conan, Kull, and Bran Mak Morn stories of R E Howard; the Grey Mouser/Fafhrd stories by Fritz Leiber; the Arthurian tetralogy by T.H. White; the Middle Earth stories of J.R.R Tolkien; “The Worm Ouroboros” by E R Eddison; the Zothique stories of Clark Ashton Smith; some of the works of Abraham Merrit (“The Ship of Ishtar”, etc.); some of H Rider Haggard’s stories (“Alan and the Ice Gods”, etc.); “The Broken Sword” by Poul Anderson; the Gormenghast trilogy of Mervyn Peake (it just gets in, I think); the Poictesme stories of James Branch Cabell (including “Jurgen,” “Silver Stallion,” and others) and “The Well of the Unicorn” by Fletcher Pratt. I would appreciate other suggestions for possible inclusions. “Titus Groan” and its sequels by Mervyn Peake actually do not have the form nor roots I have described but they have the general atmosphere and are certainly set outside of our own space-time Earth.

He was engaging in a process of sifting, and refinement.

Next came Leiber’s famous reply to Moorcock. In a letter in the pages of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society newsletter Ancalagon (issue #2, April 1961), Leiber suggested for the first time that “sword-and-sorcery” be considered:

ANCALAGON looks nice, especially the cover (where the art seems nicely gauged to the method of reproduction) and the article on fantasy-adventure—a field which I feel more certain than ever should be called the sword-and-sorcery story. This accurately describes the points of culture-level and supernatural element and also immediately distinguishes it from the cloak-and-sword (historical adventure) story—and (quite incidentally) from the cloak-and-dagger (international espionage) story too! The word sorcery implies something more and other than historical human witchcraft, so even the element of an alien-yet-human world background is hinted at. At any rate I’ll use sword-and-sorcery as a good popular catchphrase for the field. It won’t interfere with the use of a more formal designation of the field (such as the “non-historical fantasy adventure” which Sprague once suggested in a review of Smith Abominations of Yondro in AMRA) when one comes along or is finally settled on.

Leiber here added further delineation, to fictional cultures whose warriors wield swords instead of guns, and include magical elements, to separate S&S from historical adventure. His letter to Anacalagon was reprinted in the July 1961 Amra, with some amendments, and the term “sword-and-sorcery” stuck.

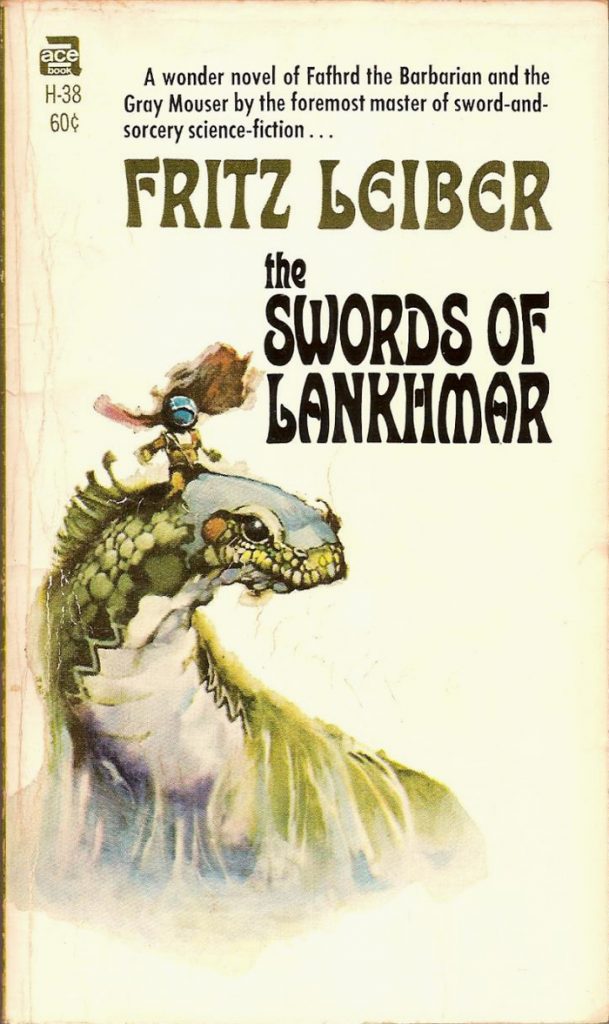

Seven years later Leiber would continue this process of sifting and refinement in the introduction to The Swords of Lankhmar (1968), making it clear he was at something grittier and more grounded than high fantasy in his tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser:

Fafhrd and the Mouser are rogues through and through, though each has in him a lot of humanity and at least a diamond chip of the spirit of true adventure. They drink, they feast, they wench, they brawl, they steal, they gamble, and surely they hire out their swords to powers that are only a shade better, if that, than the villains. It strikes me (and something might be made of this) that Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are almost at the opposite extreme from the heroes of Tolkien.

Shake, re-evaluate.

A dozen years after the famous Moorcock/Leiber exchange, the refinement continued. Lin Carter in the introduction to Flashing Swords #1(1973) connected S&S back to the pulps, creating a through-line to where this type of fantasy started:

What does Sword & Sorcery mean? A succinct definition follows: We call a story Sword & Sorcery when it is an action tale, derived from the traditions of the pulp magazine adventure story, set in a land, age or world of the author’s invention–a milieu in which magic actually works and the gods are real—a story, moreover, which pits a stalwart warrior in direct conflict with the forces of supernatural evil.

Sift, sift.

In the 70s and into the 80s the refinement continued, but mainly toward rigidity. The holes through which sword-and-sorcery could pass grew smaller until by the 80s it was seemingly only barbarians. S&S had become stagnant and fixed, which led to its commercial demise. It sat largely moribund through the 90s, until new artists came along, preceded by new ideas about what the subgenre could include, and renewed debates.

Re-evaluation and refinement are part of the process that allow genres to stay healthy and vital, not fixed, rigid forms in which only stale repetition is possible. The lesson? Instead of envisioning S&S as a formula, consider instead a mesh, or perhaps a funnel, wide at one end and narrow at the other. With that metaphor the question becomes: How fine is your definition, and what will you allow to pass through, or be caught and considered, and treasured?

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.