Of Artifacts, Relics, and Stranger Things in the Stories of Michael Moorcock

by Brian Murphy

My daughter was on my case, hard. She really wanted me to watch Stranger Things.

“Dad, you grew up in the 80s. You played Dungeons and Dragons. It’s made for you!”

At first I resisted. I’m not much of a TV guy, preferring books for my entertainment. But ultimately, I caved. When you’re a dad of a teenage daughter you don’t pass up a bonding moment, especially when one is gift-wrapped and handed to you.

So I started watching Stranger Things with my wife and daughter a few months ago and we’re almost caught up, down to the last two episodes of season 4 (no spoilers please). And I can say I’m pleased to have taken my daughter up on the offer. It’s a good show.

Stranger Things draws on bits of Dungeons and Dragons lore and brings them to a contemporary audience in a compelling way. Some of these old artifacts have ties to older stories, pre-D&D, including those of Michael Moorcock.

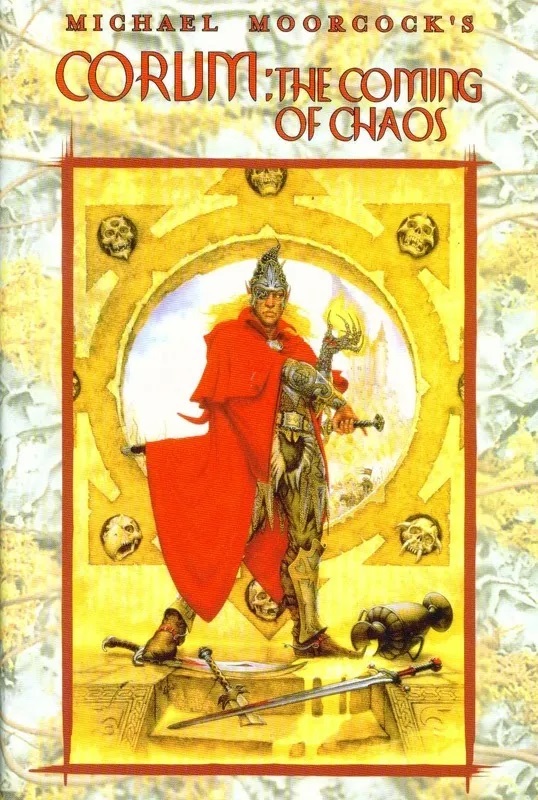

At the beginning the first Corum story, The Knight of the Swords, Corum is tortured and left horribly disfigured. To exact revenge on his tormentors Corum turns to the potent remnants of a pair of old gods: The Hand of Kwll, and the Eye of Rhynn. Which are the inspirations for The Eye and Hand of Vecna* from first edition AD&D.

The original Dungeon Master’s Guide is a tome of wild fun, in particular its chapter on artifacts and relics. I recall many memorable items—the Axe of the Dwarvish Lords, the Rod of Lordly Might—but few as cool as The Eye and Hand of Vecna. These were extremely powerful but also potentially character-destroying. From the description of The Hand of Vecna:

The host character may use any minor power without fear, but as soon as a major power of the Hand is used, he or she awakes a spirit of great evil. (You, the DM, should then begin an insidious campaign of suggestion and urging towards evil on that character’s part.) When a primary power is used, the host will instantly become neutral evil – very evil. The Hand can be severed from the host at any time before its powers are used with 100% certainty, but each major power use subtracts 1% from the probability, and each use of a primary power makes success 10% less likely. Whenever 100% subtraction has occurred there is no possibility of removing the Hand, and the character will know this.

Shiver. The Eye of Vecna is nothing to be trifled with, either:

The Eye of Vecna is said to glow in the same manner as that of a feral creature. It appears to be an agate until it is placed in an empty eye socket of a living character. Once pressed in, it instantly and irrevocably grafts itself to the head, and it cannot be removed or harmed without slaying the character. The alignment of the character immediately becomes neutral evil and may never change.

The coolest thing was rolling on a table to determine these artifacts’ powers. These included major and minor effects, both benign and malevolent, plus prime powers and side effects. You were just as likely to get the ability to turn an opponent into a quivering blob of jelly (Bones/exoskeleton/cartilage of opponent turned to jelly – 1 time/day) as you were to be struck by lycanthropy, or clumsiness. Destroying an artifact or relic was an epic adventure on the scale of The Lord of the Rings; you could bury one beneath 100 adult red dragon skulls, or drop them into the Earth Wound. Good luck accomplishing either of those! Mount Doom sounds safer.

The template for these double-edged artifacts can be found in much old literature, but also Moorcock’s stories.

With the Eye of Rhynn Corum can see into a dark netherworld. But the power is sanity blasting, and he must lower an eyepatch over the eye lest its visions destroy him. “He began to see the darker planes. Again he saw the landscape on which a black sun shone. Again he saw the four cowled figures. And this time he stared into their faces. He screamed.” Corum needs the Hand of Kwll to harness the demonic figures to his will. In exchange for their service they demand a prize, “a life for each of us.” They take many.

This literal and figurative “eye for an eye” style of demon summoning is also something D&D owes to Moorcock, probably with some of E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros thrown in as well. In Elric’s universe summoning a demon is never taken lightly. It will turn on you, given any crack in the pentagram.

Moorcock would just drop this sort of material in his stories like sowing wildflowers. It didn’t always work … but many times it did, including in his most memorable creation. Stormbringer makes Elric a fearsome foe but turns in his hand in unpredictable ways, often slaying those whom he loves. It’s such a powerful creation that it’s a character in and of itself.

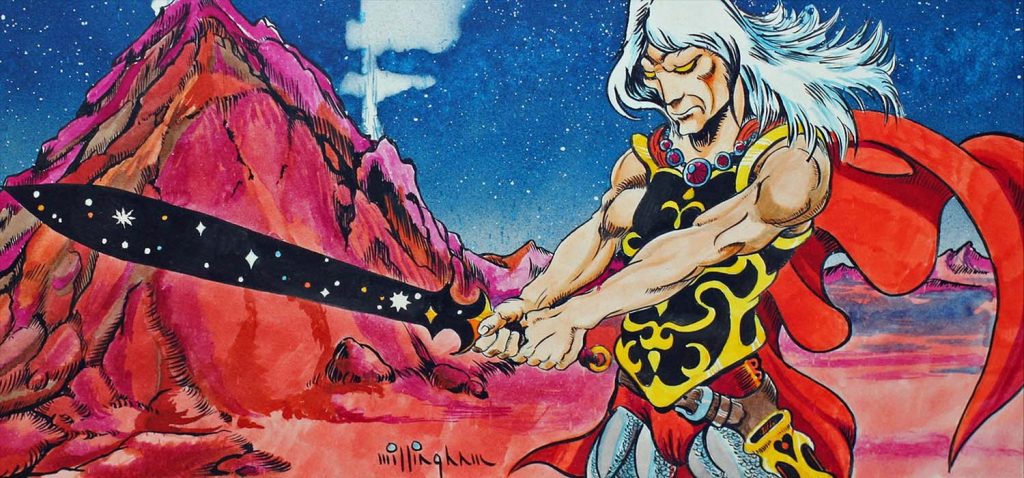

Again AD&D borrowed from Moorcock’s most potent creation with module S2, White Plume Mountain, which contains the evil sentient sword Blackrazor (if there were any doubts this is Stormbringer, Bill Willingham’s full color illustration of Elric on the back cover is the hammer on the head of the nail). Blackrazor is one of three artifacts created by the wizard Keraptis in the tangled maze of tunnels deep beneath the volcanic White Plume Mountain. A chaotic neutral sword +3, intelligence 17, ego 16, whose purpose is to … suck souls. On a killing stroke Blackrazor temporarily adds the number of levels of the dead foe to its bearer’s levels. Those killed by the sword cannot be raised.

Badass, kind of game-breaking. But AD&D was not all about balance. Just like the fiction on which its based, D&D loses something when magic becomes mundane. When players know their +3 sword functions like any reliable piece of modern machinery, they discard it as soon as a +4 sword comes along. Magic should be unpredictable and wild because it’s well, magic.

Moorcock’s endless tinkering and rejiggering of the Elric storyline makes it maddening to find a definitive timeline. Even today we’re getting new editions.

But maybe that’s the point.

Fantasy should be the stuff of disunion, and danger. Stranger Things’ Eleven not knowing if her psionic-like mind powers are a thing of good, or a corruption.

Perhaps that’s why Stranger Things got as popular as it did. There’s an element of unpredictability to the show. I struggle to describe exactly what it is. It’s not exactly horror, not quite comedy, not exactly for kids, nor sober-minded adults. Maybe adults who are kids at heart? Definitely for adults who remember their D&D days with nostalgia. You don’t know who it’s for, but you want to be part of this exclusive club.

We could all use more randomness in our fantasy. Wildness, danger, unpredictable artifacts. Stranger things. More Wizardry, and Wild Romance.

In short, a little more … Moorcock.

*’Vecna’ being an anagram of ‘Vance,’ another author who was a major source of inspiration for Dungeons & Dragons.

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.