Goodman Games and Tales From the Magician’s Skull are honored to report that this essay by Jason Ray Carney, Dehumanizing Violence and Compassion in Robert E. Howard’s “Red Nails,” has been nominated for a 2022 Robert E. Howard Award in the category of Outstanding Achievement, Essay — otherwise known as The Hyrkanian!

The Robert E. Howard Awards 2022 will be presented this weekend, June 10 at Howard Days in Cross Plains, TX, the annual celebration of the life and work of the founder of sword-and-sorcery, Robert E. Howard.

Naturally, we just had to rerun Jason’s terrific essay as we wish him the best of luck in this weekend’s fierce competition — for The Hyrkanian category also includes work from TFTMS regulars Brian Murphy and C.L. Werner! Competition like that will test the surest steel — and congratulations to all of the nominees justly celebrated for their work in enriching the legacy of one of the twentieth century’s most distinct and enduring literary voices.

Dehumanizing Violence and Compassion in Robert E. Howard’s “Red Nails”

by Jason Ray Carney

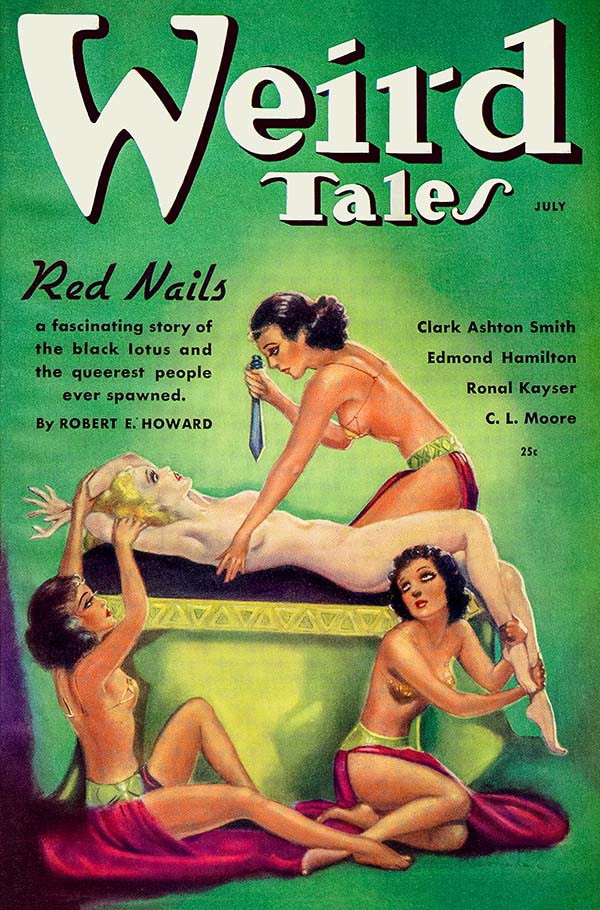

Robert E. Howard’s sword and sorcery tale “Red Nails,” published as a three-part serial in Weird Tales in 1936, tells the story of the city of Xuchotl, the enduring, blood-soaked war between the Tecuhltli and the Xotalanc, and the dehumanizing effect of sustained hatred and violence. “Red Nails” engages with several ancient literary tropes, but the one that centers “Red Nails” is what I term “the stalemate war.” By focusing on the stalemate war between the murderous Tecuhltli and insane Xotalanc, I hope to bring into focus a surprising facet of Robert E. Howard’s most famous sword and sorcery character, Conan of Cimmeria: the way the barbarian maintains his humanity through compassion.

First, let me briefly clarify what I mean by the literary trope of “the stalemate war.” Identifying tropes and patterns in literature and popular culture is more an art than a science, but it’s fun and often reveals surprising dimensions to works. Why storytellers hew to these enduring patterns, who knows? Some speculate that these mythic patterns are evolutionary residues, instinctual psychological narratives that unconsciously narrate the crucible of our evolution. Their origins notwithstanding, there are undeniable recurring structures of story that resonate with us, and so storytellers return to them over and over, hone them, and reinvent for their own purposes. Robert E. Howard did this with “Red Nails,” and he did this masterfully.

“The stalemate war” generally consists of two sides locked in a violent, hatred-fueled conflict. At the beginning of the story, the original cause of the conflict is often obscured by the passage of time and has been forgotten by both sides; therefore, the war has become interminable, even absurd. The original injustice cannot be rationally judged and righted because, sadly, no one really understands it or cares about it. Raw thirst for blood now defines the unending conflict. Each sides’ victory conditions have become amorphous, dangerously ill-defined; if they are expressed, victory consists, quite simply, in the complete destruction of the enemy. The war has become one of mutual extermination because reconciliation between the two sides is no longer possible; the conflict has festered to the extent that both sides have completely dehumanized the other side and they have dehumanized themselves as well. A key feature of the trope is that the lives of the combatants have become a kind of strange, ahistorical purgatory, where nothing happens except violent death after violent death. History doesn’t proceed amidst this never ending, bloody melee.

I dare say the stalemate war has a robust presence in literary history. Although a detailed survey of the trope could reach book length, a brief treatment here will be helpful before deploying it as a lens through which to analyze Howard’s “Red Nails,” Xuchotl, and the holocaust war between the Tecuhltli and the Xotalanc.

It might be fair to suggest that the stalemate war emerges in literary history with the Trojan War, that mythic conflict that centers Homer’s epics (although previous oral culture iterations no doubt preceded Homer). It can be glimpsed in later classical literature, often in the dramatic histories of Greek and Latin historians (e.g. Herodotus’s treatment of the Greco-Persian conflicts; Tacitus’ and Plutarch’ treatment of the Roman empire’s perpetual conflict with Parthia). The stalemate war carries on into Medieval European literature as well. Consider, for example, Dante’s Comedy, which is permeated by allusions to the perpetual struggle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Dante’s depiction of the Phlegethon, the river of boiling blood, where the violent and warlike are perpetually tormented by centaurs, is a powerful rendering of the stalemate war. Shakespeare’s historical plays are rife with compelling poetic treatments of the Hundred Years War. And so on.

Robert E. Howard’s “Red Nails” is a powerful interwar version of the stalemate war. Partly inspired by Howard’s visit to Lincoln, New Mexico in 1935, the site of the Bloody Lincoln County War (1878) (as speculated by Howard scholar, Patrice Louinet), in telling the story of Xuchotl, Howard renders the participants in the interminable war as insane, obsessed with revenge, even to the extent that they have abandoned their very humanity. Before proceeding, let me briefly summarize the plot (spoiler alert):

The story begins with Valeria of the Red Brotherhood fleeing enemies. She has struck out into a wasteland in order to escape. She discovers, to her annoyance, that she has been followed by Conan, who, unbeknownst to her, has helped her escape. As Valeria and Conan are bickering, they are attacked by a reptilian monster. Although Valeria and Conan are briefly trapped by the monster, they succeed in killing it. Fearing that more monsters will come, they flee the wasteland to a city ruin, hoping to find water, food, and shelter. This ruin turns out to be the accursed city of Xuchotl, which is a massive network of corridors, towers, chambers, mazes, and catacombs. Worse still, in Xuchotl, Conan and Valeria become embroiled in a war that has been waging between two factions–the Tecuhltli and the Xotalanc–for several centuries. The war between the Tecuhltli and the Xotalanc is particularly gruesome: the Tecuhltli nail a copper nail into a black pillar for every enemy killed; accordingly, the Xotalanc take pleasure in beheading their enemies and morbidly preserving their gruesome heads for charnel display. With Conan and Valeria’s aid, the Techultli triumph over the Xotalanc; alas, even as this faction triumphs, they betray Conan and Valeria. The story concludes when the Techultli are themselves slaughtered when a sin from their past returns to haunt them. In the end, Conan and Valeria are the only ones left standing, surrounded by corpses, in the graveyard quiet of a suicided city.

The inhabitants in war-haunted Xuchotl are described as insane throughout the story. Consider Valeria’s first glimpse of a member of the Techultli faction: “She caught the wild eyes among the lank strands of black hair.” Or consider Valeria’s observation when she meets the warrior Techotl, who later becomes an ally: “In his eyes, behind the glow of terror, lurked a weird light she had never seen in the eyes of a man wholly sane.” Or consider when Conan listens to Olmec, Prince of the Techultli, describe the eternal warfare of the city:

With his weird eyes blazing, Olmec spoke long of that grisly feud, fought out in silent chambers and dim halls under the blaze of the green fire-jewels, on floors smoldering with the flames of hell and splashed with deeper crimson from severed veins. […] Without emotion Olmec spoke of hideous battles fought in black corridors, of ambushes on twisting stairs, and red butcheries. With a redder, more abysmal gleam in his deep dark eyes he told of men and women flayed alive, mutilated and dismembered, of captives howling under tortures so ghastly that made even the barbarous Cimmerian grunt.

Finally, consider Valeria’s paranoid reflections as she prepares to sleep in the strange city: “These people were neither sane nor normal; she began to doubt if they were even human. Madness smoldered in the eyes of them all.”

The stalemate war in Xuchotl has fully dehumanized the inhabitants of the city. In their shedding of all human compassion, they have lost their humanity, have become monsters.

Surprisingly, the two death-dealing protagonists, Conan and Valeria, maintain their humanity by practicing compassion for each other. This is a bold claim about our beloved Cimmerian and the She-devil of the Red Brotherhood, so bear with me as I elaborate. Conan the Compassionate? Really?

At the beginning of “Red Nails,” Conan has followed Valeria into danger. Why? Because he sympathized with her, understood the reason she became an outlaw, why she knifed a Stygian officer who tried to force himself on her. Referring to the Stygian and his unwanted advances, Valeria tells Conan, “You know what my provocation was.” Conan responds, “If I’d been there, I would have knifed him myself.” The violent topic of their conversation notwithstanding, Conan is showing compassion for Valeria here. He understands her provocation and sought to help her due to his sympathy.

Moreover, when Valeria asks Conan why he trailed her, he responds with a question: “Haven’t I made my admiration for you plain ever since I first saw you?” Valeria answers, “A stallion could have made it no plainer.” Although sexual desire for Valeria is indeed central to Conan’s admiration, the narrator is clear to state that her body is not the only element that Conan values. Consider the scene where Valeria, annoyed as Conan continues to force his unwanted help, brandishes a sword and demands that he leave her be:

He was angry, yet he was amused and filled with admiration for her spirit. He burned with eagerness to seize that splendid figure and crush it in his iron arms, yet he greatly desired not to hurt the girl. He was torn between a desire to shake her soundly, and a desire to caress her. He knew if he came any nearer her sword would be sheathed in his heart. He had seen Valeria kill too many men in border forays to have any illusions about her. He knew she was quick and ferocious as a tigress.

Later, after Conan and Valeria have been attacked by a monster and are resting before proceeding to the ruins of Xuchotl, Conan again shows compassion for Valeria. He volunteers for the first watch of the night, and when she states, “Wake me when the moon is at its zenith,” he ignores her. “Her last impression, as she sank into slumber, was of his muscular figure, immobile as a statue hewn out of bronze, outlined against the low-hanging stars.” Conan, of course, does not wake Valeria and instead watches the whole night, and when she comments the following morning, Conan responds, “‘You were tired […] Your posterior must have been sore, too, after that long ride. You pirates aren’t used to horseback.'”

Later on in the story, after a gruesome battle between the factions, Conan’s compassion for Valeria becomes pregnant with meaning by way of contrast to the inhumanity and lack of compassion evident in the triumphant, animal-like roaring of the bloody Techultli:

It was not a human cry of triumph. It was the howling of a rabid wolf-pack stalking among the bodies of its victims. Conan caught Valeria’s arm and turned her about. ‘You’ve got a stab in the calf of your leg,’ he growled. She glanced down, for the first time aware of a stinging in the muscles of her leg.

Moments later, in response to the prince of the Techultli’s animalistic crowing about their gruesome triumph, Conan further reveals his compassionate nature: “‘You had better see to your wounded,’ grunted Conan, turning away from [the Prince]. ‘Here, girl, let me see that leg.'”

We are more familiar with Conan as a death-dealer than as a healer or battle medic, but in this scene, his actions, thrown into stark relief by the context of the blood-drenched stalemate war, Conan maintains his humanity through his compassion, his respect for life and the living. Indeed, the compassion Conan and Valeria show for each other mark them as human in contrast to the dehumanized, monstrous inhabitants of Xuchotl. Consider Valeria’s suspicious observation about the Techultli healer who bandages her leg: “A little while before, Valeria had seen this same woman stab a Xotalanca woman through the breast and stamp the eyeballs out of a wounded Xotalanca man.” Valeria struggles to see the woman’s humanity after her display of extreme violence.

Moreover, Conan is no tribalist. His surprising compassion does not only extend to Valeria, who he physically desires and respects as a warrior. It extends to some of the diabolic inhabitants of the degenerate city. Conan and Valeria legitimately befriend one member of the Techultli faction, Techotl, and through their friendship seem to redeem his lost humanity, to restore him from a monster dehumanized to hate to a human nourished by compassion. As Techotl lays dying, betrayed by his Prince, the narrator describes what Conan’s kindness and compassion meant to him:

Techotl’s groping fingers plucked at Conan’s arm. In the cold, loveless, and altogether hideous life of the Techultli his admiration and affection for the invaders of the outer world formed a warm, human oasis, constituted a tie that connected him with a more natural humanity that was totally lacking in his fellows, whose only emotions were hate, lust, and the urge of sadistic cruelty.

In providing the murderous Techotl friendship, Conan allows the hatesick warrior to die a human and not a monster.

Let me conclude my analysis of “Red Nails,” arguably one of Howard’s bloodiest Conan tales, with a surprisingly touching image: a scene of healing and affectionate embrace. Surrounded by the dead and dying, in the quiet of a city that has effectively committed suicide, our heroes tend to each other’s wounds as both healers and lovers:

‘You need a bandage on that leg.’ Valeria ripped a length of silk from a hanging and knotted it around her waist, then tore off smaller strips which she bound efficiently to the barbarian’s lacerated limb. ‘I can walk on it,’ he assured her. ‘Let’s begone. It’s dawn outside this infernal city.’ […] The old blaze came back in his eyes, and this time she did not resist as he caught her fiercely in his arms.

Here Conan and Valeria break the stalemate and rise above the hate. Deadly killers themselves, they nevertheless assert their humanity not by killing but by an act of healing and loving embrace.

Publication History: This essay is based upon a longer presentation given at “The Glenn Lord Symposium” in June of 2019. “The Glenn Lord Symposium” is an REH-focused Academic Symposium nested in “Robert E. Howard Days,” an annual fan festival and convention held in Cross Plains, Texas that honors Robert E. Howard and his literary legacy.