Fueling the Fire of Fantasy Fiction: Gaming’s Influence on Today’s Writers

by Brian Murphy

After taking a bit of a controversial stance last week with my piece on the possible detrimental effects of gaming on sword-and-sorcery, I will now take the opportunity to rebut … myself, and offer the opposing side a chance. And discuss the net positives that role-playing and, in particular, Dungeons and Dragons has had on fantasy fiction.

As I mentioned in my prior piece, gaming can, and in many instances has, inspired gamers to take up a pen and launch successful careers as fantasy authors. Before they were writers, the likes of China Mieville (author of Perdido Street Station), Cory Doctorow (Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom), and Joe Abercrombie (First Law trilogy, The Heroes) were slinging dice at the game table. George R.R. Martin is another notable author who sings the praises of role-playing, though he had started writing in 1971, prior to the invention of D&D.

A good dungeon master should combine both the left-and-right-brained traits of organized design and on-the-fly storytelling in order to create a believable world and populate it with memorable characters, monsters, and compelling scenarios for exciting gameplay. The same can be said of an author. A 2014 New York Times article by Ethan Gilsdorf, “A Game as Literary Tutorial,” tells the story of author Junot Diaz, an immigrant boy growing up in New Jersey in the early 80s. Unmoored and adrift, Diaz found a welcome refuge in gaming, as well as “a sort of storytelling apprenticeship” that laid the groundwork for a remarkable writing career. Diaz later went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his work and teach writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Gaming has introduced millions to the broader fantasy genre, bringing them to the game table and thereby expanding the audience for authors. According to this article by Dice Cove, some 50 million people have played D&D since its inception in 1974. In 2020 alone, Wizards of the Coast grew some 24% and generated more than $816M in revenues. Today, D&D is more popular than ever, even more so than its early 80s heyday when I and many others were first introduced to the game. It痴 so popular in fact that people are lining up to watch others play: the live-play D&D program Critical Role has generated $10M in revenues, capturing some 53,000 viewers for marathon streaming four-hour game sessions. Writers need readers if they are to make a living at their craft, and D&D and the broader field of RPGs bring with them a very sizable audience.

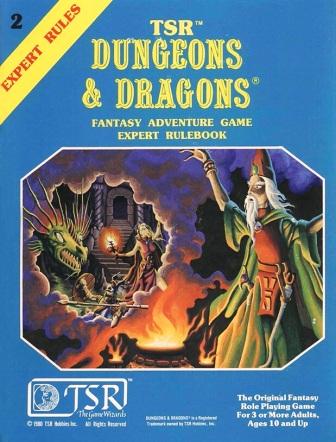

Games can serve as signposts to fantasy fiction. The Old School Renaissance, which began on websites like Dragonsfoot and the Knights and Knaves Alehouse, morphed into a guerilla blog movement of content creators and led to the development of commercial products and companies, has opened the door to the revival of the classic literature that inspired the creators of D&D. The OSR set out to illuminate and revive “old school” gameplay as exemplified by the likes of the “little brown books,” first edition AD&D, and Moldvay/Cook and Holmes basic editions. This style is noted for its emphasis on dungeon crawls and loot accumulation, weird and atmospheric spell descriptions, and fast and loose, on the fly DM adjudications. Many of these elements can be traced directly back to pulp fantasy, pre-Tolkien fantasy, and sword-and-sorcery.

The OSR heralded a renewed appreciation and exploration of the famous Appendix N, the list of games at the back of the first edition AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide that patron saint Gary Gygax recommended as sources for inspirational reading. Many gamers (hello, self!), seeking to improve the fun and inject new ideas at the game table, went back to the likes of Poul Anderson, L. Sprague de Camp, Jack Vance, and Fritz Leiber and read these amazing stories, becoming lifelong fans and readers of sword-and-sorcery.

Today we are seeing games that channel sword-and-sorcery even more effectively than D&D, offering a prospective blueprint for what makes this type of fiction tick. The likes of Astonishing Swordsmen and Sorcerers of Hyperborea, Barbarians of Lemuria, Old-School Essentials, and (of course!) Dungeon Crawl Classics have moved games back into a sword-and-sorcery mode, capturing the days of high adventure with a free-flowing, swashbuckling play-style. This site’s own Tales From the Magician’s Skull takes the stories of modern sword-and-sorcery authors and translates them into game mechanics and offers suggestions for making them work at the game table. These games have shown that fiction and gaming can produce a fruitful interplay, a nexus of creativity that benefits both gameplay and storytelling.

So what are we to take from these two seemingly opposing viewpoints? Perhaps that the impact of gaming on sword-and-sorcery and fantasy fiction as a whole is a multifaceted, complex story.

Gaming has and will continue to inspire new ranks of authors. Gaming based on sword-and-sorcery styles of fiction points gamers toward this style of fiction, and possibly converts them as readers.

Gaming at the table needs to be acknowledged as something different from writing fiction, and in profound ways. The magic of gameplay is captured in spontaneity, the unplanned moments between player and DM or player-to-player. Fiction authors likewise experience moments of serendipity during their sessions, but storytelling on the page is more than capturing cinematic moments of drama; it also needs to portray mood, and symbol, and be rendered with a compelling style, and told with proper pacing. These are skills that are honed through hours and hours of practice and repetition. Hallmarks of good fantasy fiction are creativity, originality, and unpredictability. Robert E. Howard drew upon elements of historical fiction and horror, melded them together in the pages of Weird Tales, and created something new and exciting and enduring. Karl Edward Wagner melded Gothic influences with the likes of E.C. Comics and E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros and created the unique sword-and-sorcery hero-villain Kane. Fantasy fiction that relies on an ordered set of game rules as its foundation, or seeks to recapture free-flowing moments of social serendipity at the game table without applying the rules or discipline of good storytelling, is not likely to capture the imagination of readers, nor stand the test of time. The two mediums, gaming and writing, share some commonalities but are ultimately different disciplines.

But, each can fuel the other.

It is possible for both sides of his story to be true, that D&D both spurred many authors to take up the pen while simultaneously having a detrimental impact on the readership of sword-and-sorcery fiction as a whole. Undoubtedly gaming profoundly changed the trajectory of fantasy fiction and will continue to do so well into the future.

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.