Appendix N Birthday: Lord Dunsany (also known as Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany)

by Michael Curtis

Our Adventures in Fiction series is meant to take a look at the writers and creators behind the genre(s) that helped to forge not only our favorite hobby but our lives. We invite you to explore the entirety of the series on our Adventures In Fiction home page.

Lord Dunsany’s birthday was July 24th — this is our belated well-wishing.

Some Appendix N authors directly influenced the creation of fantasy role-playing. We see concrete inspiration in the trolls borrowed from Poul Anderson or the “Vancian” magic system of D&D. Other Appendix N writers exerted a less obvious influence, providing more a sense of tone and wonder than any specific element. It can be argued, however, that one Appendix N author wielded the greatest influence on fantasy role-playing not because his works were borrowed wholesale or served to color Gygax and Arneson’s campaigns, but because he inspired numerous other Appendix N writers, impelling them to create the stories from which RPGs derive their origins.

Few would recognize the name Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, but many more know him by his title, Lord Dunsany (pronounced Dun-SAY-ny), whose birthday we honor today. Dunsany created an impressive literary body of work over a period of fifty years, penning dozens of novels and plays and hundreds of short stories. He seems to spring from nowhere, publishing The Gods of Pegana in 1905, a print he subsidized due to his lack of literary reputation. This would be the only time he ever paid to publish his own book. The Gods of Pegana was a beautiful work of imaginative mythology, presenting the reader with a pantheon of gods hitherto unseen in the western world. With a style as archaic as the King James Bible, but with all the wonder of pastoral myths spoken in the hills overlooking the Mediterranean, The Gods of Pegana is a transformative work, one that left an indelible mark on the landscape of fantasy fiction.

Much like Clark Ashton Smith, who followed in Plunkett’s wake, Lord Dunsany’s tales are more prose poetry than pulp. He evokes a sense of otherworldliness in his stories, whether he’s writing about the “sign of Mung” or the constant drumming that keeps the creator god Mana-Yood-Sushai asleep and dreaming so that the universe may continue. To read Dunsany is to fall willingly into that vague realm which lies somewhere between imagination and sleep, a place where even truly outlandish notions possess a gravity and beauty that keeps them intact in the face of logical scrutiny.

Dunsany would revisit the strange gods of Pegana in a sequel, Time and the Gods, but he had other tales to tell beyond those mythological entities. Many of his short stories straddle the line between prose poetry and sword & sorcery. “The Sword of Welleran” or “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth,” feature heroes grimly facing off against seemingly insurmountable odds. His novel, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, gives the reader a faerie tale in the literal sense, telling what happens when mortals dare to seek an Elfland bride and why wishing for magic is not always—or ever—a good idea. Even his tales set in the modern world skirt the verges of the fantastic. One of Dunsany’s more famous creations, Joseph Jorkens, a dubious storyteller who haunts a gentlemen’s club (the sophisticated kind) and tells questionable tales so long as the whiskey is forthcoming, regales the reader with stories of walking trees and vanishing towns that could easily be set in Middle-earth or the Young Kingdoms.

There are few 20th century fantasy authors of merit who weren’t affected by Dunsany’s writings, several of whom grace the Appendix N list. J.R.R. Tolkien owes a debt to Dunsany, as does Fritz Leiber. Ursula K. Le Guin and C.L. Moore have both acknowledged Dunsany’s influence, with Moore summing up his genius by stating “No one can imitate Dunsany, and probably everyone who’s ever read him has tried.”

One of these imitators was no other than H.P. Lovecraft, who openly admitted that many of his early works were essentially Dunsany fan fiction. Lovecraft, like many before and after him, fell under Plunkett’s enchantment and wrote his own tales of strange gods dwelling in nearly unpronounceable lands. If you’ve ever read “The White Ship,” “The Doom that Came to Sarnath,” “Polaris,” or “The Cats of Ulthar,” you’ve experienced the works of Dunsany twice-removed. But as always, Dunsany did them better and Lovecraft developed his own authorial voice as he improved as a writer. However, he never quite escaped the gravity of Dunsany and it’s difficult to read Plunkett’s “Idle Days on the Yann” or “A Shop on Go-By Street” without feeling like you’ve discovered the template for The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.

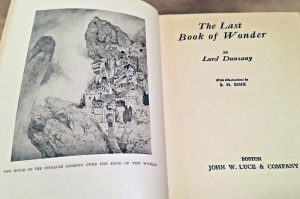

Dunsany’s influence on those who in turn influenced fantasy role-playing is quite clear, but can we draw a more direct connection between his work and D&D and its descendants? The answer is yes, and it’s an easily overlooked one. The connection can be found in a tale originally published in Dunsany’s collection of short stories entitled The Book of Wonder.

The story in question is “How Nuth Would Have Practiced His Art Upon the Gnoles.” In this tale, Nuth attempts to steal from a house in a dark forest occupied by “gnoles,” bestial creatures with a love of emeralds. At the risk of spoiling a story from 1912, things don’t go well for Nuth. Margaret St. Clair, another name from Appendix N and yet another example of a fantasy author finding inspiration in Plunkett’s work, revisited Dunsany’s creation in her 1951 story, “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles.”

The “gnoles” of both tales are the inspiration for the gnolls of Dungeons & Dragons. In the original D&D set, this connection is clear if somewhat marred by a typo. In Vol. 2: Monsters & Treasure, the entry for gnolls reads “A cross between Gnomes and Trolls (…perhaps, Lord Sunsany [sic] did not make it all that clear) with a +2 morale.” Despite the misspelling of “Dunsany,” it is clear Gygax has either Plunkett’s story or St. Clair’s follow-up in mind when writing the monster description. This article’s author would draw much stronger connections between Lord Dunsany—spelled correctly this time—and fantasy role-playing in the Dungeon Crawl Classics adventure, “Gnole House,” acknowledging Plunkett’s contribution to the hobby in clear terms (and hopefully providing an entertaining adventure to boot).

Lord Dunsany, while astoundingly influential on those who inspired fantasy RPGs, remains largely overlooked by modern readers. Most people are more familiar with his imitators than Dunsany, himself. This is a crime and any lover of fantasy fiction is doing themselves a disservice by not hunting down a Dunsany collection or two for their personal libraries. Dunsany can inspire entire campaigns with a single throw-away line or cause the reader to reflect on their own lives (“In the Land of Time” becomes more and more profound the older I get) with equal aplomb. I can think of no better way to celebrate his birthday than by willingly putting yourselves under his literary spell and experiencing what so many other fantasy writers have felt: the urge to create fantastical stories of your own.