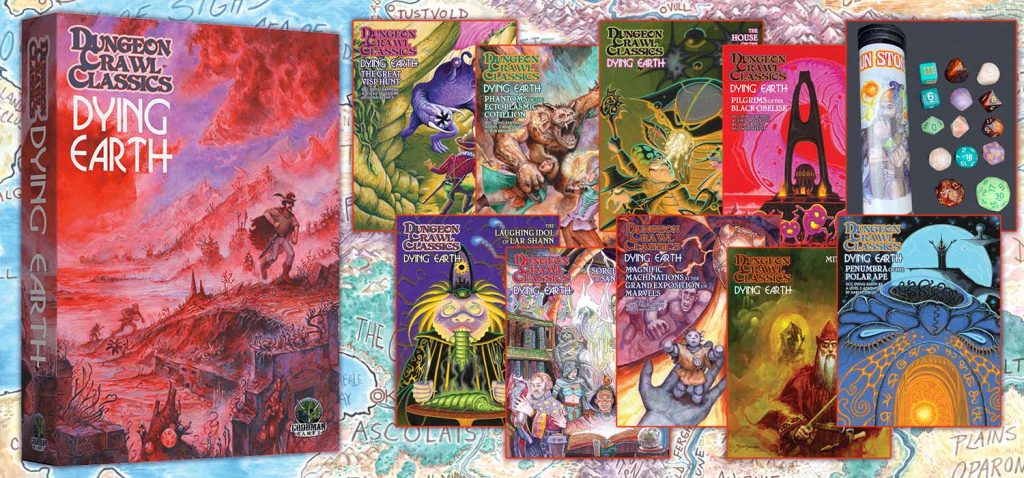

We’re celebrating the release of DCC Dying Earth all this Month with articles in honor of Jack Vance.

The Dying Earth: A Case for Sword-and-Sorcery

by Brian Murphy

Travel into the future: to an earth with a dwindling red sun that meekly fills a dark blue sky; an earth that is on the brink of dying out; an earth where science and magic mean the same thing.

~ back cover blurb, Tales of the Dying Earth, Tor Books

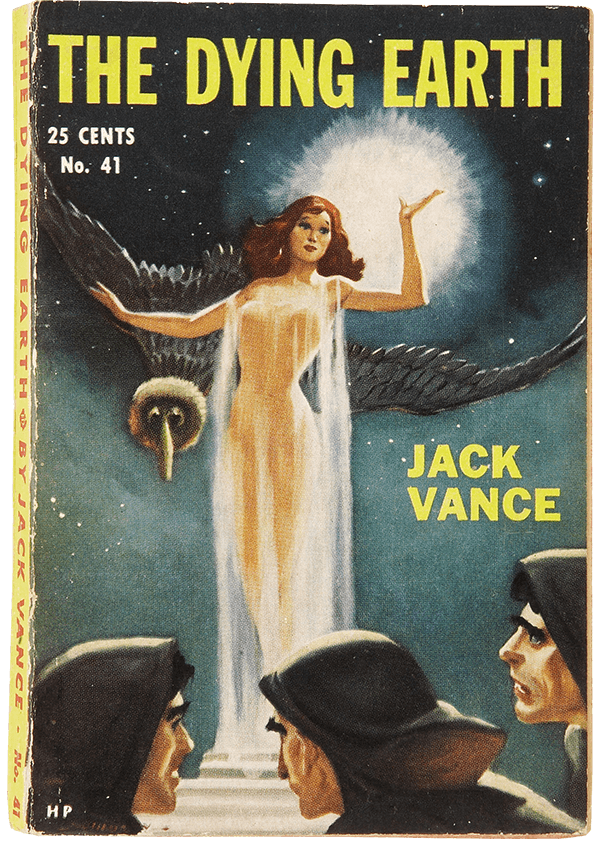

In 1950 sword-and-sorcery was at a particularly low ebb, barely registering a pulse. Weird Tales was on its last legs, and had long ceased publishing sword-and-sorcery. The well-regarded but short-lived Unknown had come and gone, and the fanzine Amra had yet to unleash its roar. Even Conan was hard to find: Gnome Press published Conan the Conqueror that year, but there were no mass-market Lancer paperbacks, no Conan comics, to bring new readers into the fold. Science-Fiction was in the ascendancy, the darling of fans.

In that same year Hillman Periodicals released Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth, a title that still defies easy description. What was this strange new book―science fiction, fantasy, or some combination (science-fantasy)?

Or, just maybe, a sword-and-sorcery lifeline?

But before we get to that, it’s fair to ask, does it matter?

On one level, not really. All that matters is whether a book is worth reading. I love sword-and-sorcery, and we need more of it, but I don’t recommend using genre studies as a purity checklist. That way leads to stultification and bad pastiche. Embrace your influences, but strive to write something new. Vance did that with The Dying Earth, and the result was an amazing and unique work, regardless of what it is or where it falls.

But I enjoy these sorts of discussions, too, and believe there is some value in having them, both from a literary/academic perspective (genres allow us to spot reoccurring themes and conventions, joint influences, etc.), and for the simple matter of recommendation’s sake. If a friend enjoys Fritz Leiber or Poul Anderson, hand them a copy of The Dying Earth, not Foundation or Harry Potter.

So, returning the question of how to classify The Dying Earth, let’s start with the macrocosm: Is it science fiction, or fantasy? Vance was a noted, prolific writer of science-fiction. He won his first Hugo Award in 1963 for The Dragon Masters, and again in 1967 for The Last Castle. Both are science fiction. Fantasy is typically set in some deep, prehistoric/antediluvian era of our own earth (Howard’s HyborianAge of Conan, Tolkien’s Middle-Earth), or on a secondary world (Fritz Leiber’s Nehwon, C.S. Lewis’ Narnia). The Dying Earth takes place in the future, one that, shorn of Vance’s creative flourishes, will be our own. Our sun will eventually decay, burning as a red giant, then sputter out and die, though fortunately not for an estimated 7-8 billion years. That all seems speculative, and SF enough.

However, science fiction is said to be about what could be but isn’t; fantasy is about what could not be. The Dying Earth clearly treats with the latter. Its unapologetic use of magic does not square with science. There is no plausible, rational explanation for memorizing an arcane formula and firing off an Excellent Prismatic Spray. Weird monsters–grues, leucomorphs, and deodands―stud the landscape of The Dying Earth, along with terrifying creations like Chun the Unavoidable.

So, if we grant that it’s fantasy, what evidence do we have for sword-and-sorcery? One is the opinion of arguably the greatest champion, anthologist, and earliest historian of sword-and-sorcery: Lin Carter. Carter in his Flashing Swords #1 anthology included “Morreion,” from The Dying Earth. Flashing Swords #4: Barbarians and Black Magicians went back to the Dying Earth well with “The Bagful of Dreams,” a chapter from Cugel’s Saga. I’m not saying Carter was perfect in his choices, or in his criticism. But the fact that he put Vance in his sword-and-sorcery anthologies, and made him an original member of the Swordsmen and Sorcerer’s Guild of America (S.A.G.A), alongside stalwarts Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, and Poul Anderson, bears weight.

A few of the stories show the clear stamp of sword-and-sorcery. “Ulan Dhor” features a fearless, skilled swordsman on a quest to steal ancient tablets of lore from a forgotten city, still ruled by a half-mad wizard-god. The hero pits his sword arm, clear vision, and relentless will against the forces of religious superstition, conformity, and autocracy―and manages to rescue a beautiful woman and ride off with her into the sunset.

There are other S&S indicators. Vance was a master stylist, one of the best fantasy has to offer. But his prose is absent the elevated, medieval archaisms and formal structure of a William Morris. The modern style is there, as is the fast pacing, the latter of which owes more to pulp-derived literature than classic, secondary world high fantasy. Vance grew up reading Amazing Stories and Weird Tales and The Dying Earthbears many of their hallmarks; they are “action tales derived from the traditions of the pulp magazine adventure story,” to borrow another phrase from Carter. Short, standalone stories, picaresque, connected via shared universe, not a grand narrative in which the world can or must be saved.

Finally, The Dying Earth is peopled with protagonists that range from indifferent to mercenary to outright scoundrels, most notably Cugel the Clever. Cugel’s Saga takes Cugel on a mission of personal vengeance. He believes Iucounu the Laughing Magician has done him a great wrong―though in truth, Iucounu inflicts his “unfair and cruel” punishment only after catching Cugel in an attempted robbery. The taleunfolds with amusing scrapes and escapes as Cugel scrabbles for coin, women, and food, a wandering outsider in strange lands. This template for a roguish hero was likely derived from James Branch Cabell, a joint influence on both Vance and Robert E. Howard. From the likes of Conan to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, to Michael Moorcock’s Elric and Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, sword-and-sorcery protagonists often operate in the gray. So too do the “heroes” of The Dying Earth, and Vance’s subsequent stories set in that universe.

In short, Vance wrote superbly in science-fiction, but also fantasy, and The Dying Earth is clearly the latter. Whether it is sword-and-sorcery is debatable; your decaying sun may set on some other categorical universe. But I’ll take it in mine.

Brian Murphy is the author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Learn more about his life and work on his website, The Silver Key.