Our Appendix N Archeology and Adventures in Fiction series are meant to take a look at the writers and creators behind the genre(s) that helped to forge not only our favorite hobby but our lives. We invite you to explore the entirety of the series on our Adventures In Fiction home page.

Appendix N Archaeology: Edgar Allan Poe

by Bradley K McDevitt

Part One: The Writer

Ok, class, before we start… let’s have a show of hands. Who here thinks about reading Edgar Allan Poe and gets traumatic flashbacks to seventh grade English?

I thought so. Having the father of the modern horror story force-fed us tends to have that effect, as opposed to other lesser writers like Lovecraft, Howard, or Tolkien, all of whom we had to discover on our own.

So even when Joe Goodman suggested doing some Appendix N Archaeology articles, I had not thought of the Bard of Baltimore until he suggested revisiting Poe. And in retrospect, decades from those dreaded reading assignments, I can think back, remember stories like The Pit and the Pendulum, The Masque of the Red Death, and The Telltale Heart and realize that he was, more than Hawthorne or Stoker, the father of modern horror fiction. Before Poe, there were horror stories and novels like Varney the Vampire or Geoffrey Lewis’ The Monk, but the majority were more morality stories than anything else or ended, Scooby-Doo-style, with the villains unmasked as mere charlatans.

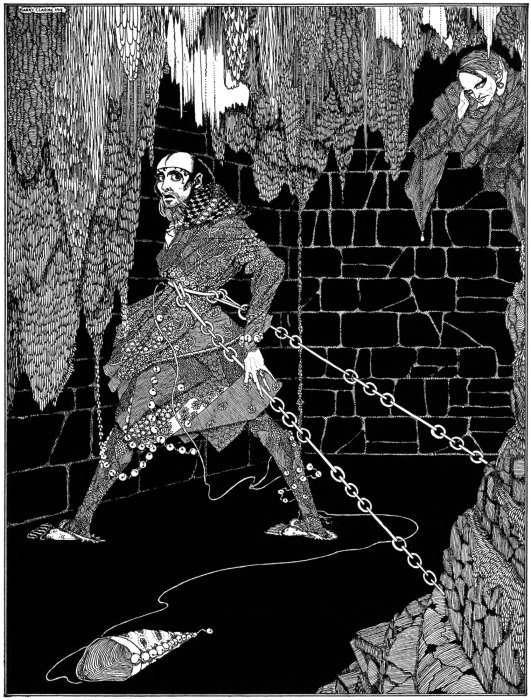

Poe was the first successful writer to pen stories intended with no purpose but to ensure the reader would not have pleasant dreams that night. I dare anyone suffering from claustrophobia to go back and read A Cask of Amontillado or The Black Cat and then sleep with the lights off. Go ahead, I double-dog dare you.

Other stories still retain their power, too. One can easily trace a line from The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar to Lovecraft’s classic death-survival story Cool Air. And modern horror writers like Clive Barker call back to Poe explicitly with stories like The New Murders in the Rue Morgue.

Poe suffers what I might be inclined to call “Shakespeare Syndrome”—being archly informed how important he is has clouded our perception as to how important he actually is.

Poe did not write much science fiction, and fantasy as a literary genre would not come to exist for almost fifty years after his unfortunate demise. But when it comes to horror and his influence on Appendix N authors like Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith, Poe’s works must be considered seminal.

Now, if you will all excuse me, it is near midnight and I hear a rap-tap-tapping at my chamber door. Some late visitor, I am sure, only this and nothing more…

For my next installment, I shall be discussing some of Poe’s lesser-known tales of terror like William Wilson, The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether, and The Descent into the Maelstrom.

In the meantime, you can find collections of his works at your local library or bookstore, or at any number of online repositories of Poe’s fiction—horror, detective, and humor—at sites like Poe Stories, House of Usher, or his section at Project Gutenberg.

Part Two: Edgar Allan Poe’s Other Works

Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson did not dream up the background ideas of Dungeons and Dragons out of thin air. Fans of fantasy fiction, they had borrowed liberally from Tolkien, Howard, Lovecraft, Moorcock, Leiber, and many others to build their game. These authors were among many the others who inspired Appendix N. But those authors were inspired by other, older authors. This article, among others in this series, takes a look at some of the writers that inspired Appendix N.

In the previous section, I examined one of the titans of weird fiction: the legendary Edgar Allan Poe. Poe is an author that, while well-known, has come to be viewed as something of an albatross to be worn around the necks of high school English students: someone to be read as a duty, not something to be enjoyed. I suggested that, far from the confines of the classroom, a new reading of Poe would be an eye-opener.

His work, while inching towards its second century of publication, stands the test of time more than adequately. Some of his stories, like A Cask of Amontillado, very much deserve their reputation as classics of horror fiction. Further, they are potential gold mines for judges looking for inspiration. It would be easy work, for example, to convert the room that forms the setting of The Pit and the Pendulum into a Grimtooth-style trap.

All one needs to do is to peruse any anthology of his work with an eye towards being inspired. One caveat, though, for a reader looking to make it a short trip: Poe was a prolific writer. Between dozens of poems, pieces of literary criticism, a novel, and humorous hoax pieces (The Balloon Hoax), it seems amazing he found time to create an entirely new genre of fiction (mysteries) and still pen dozens of horror stories still read today.

Everyone knows iconic pieces like The Masque of the Red Death and The Pit and the Pendulum, if only from the Roger Corman movies from the 1960s. Poe, however, penned many other stories that are not as well known except to those readers who have gone hunting for them. This article seeks to shine a spotlight on some of those other works of horror, madness, and even proto-science fiction. So let us put The Tell-Tale Heart aside and study another tale of madness…

The Oval Portrait

Hardly more than a vignette, The Oval Portrait would be a good single session one-on-one encounter for a game like Call of Cthulhu. It shows with great skill that Poe understood that what goes on inside a person’s mind can be more terrifying than any supernatural shenanigans. The plot is dirt-simple. The narrator is convalescing in a room adorned with many paintings, and reading a book describing the back story of each painting, much like one would buy at any art museum store. One particular painting catches his eye, a portrait of a young woman. He decides to peruse the chapter about it, and the tragedy he reads about forms the rest of the text.

This is no Pickman’s Model with a last-sentence shock ending. Poe sets up how the story is going to end well in advance, given the short length of the tale. An artist’s drive to perfection and his model/wife’s twin obsession with helping him achieve that goal is all that is needed. The reader is helplessly dragged along towards the inevitable end, even as they can see it coming.

A Tale of the Ragged Mountains

Poe wrote a time-travel story fifty-one years before HG Wells published his seminal novel of chronal adventure. And like many early science fiction pieces, A Tale doesn’t worry about the mechanics of time travel: the narrator, instead, simply gets lost in the mist during a woodland stroll outside Charlottesville, Virginia. He then ends up backward in time in India almost fifty years previously, during a riot against the ruler of the time. He ends up being “killed” before returning to his present-day body, only to die of a wound similar to that which killed him in the past.

The story is not flawless. Poe spends a significant portion of the text on a physical description of the main character… which ultimately has little to do with the plot. But the vivid, almost jewel-like description of the dream-Calcutta make up for that weakness. It gives off a very Dreamlands feel to readers familiar with the works of HP Lovecraft. And finally, speaking of Lovecraft…

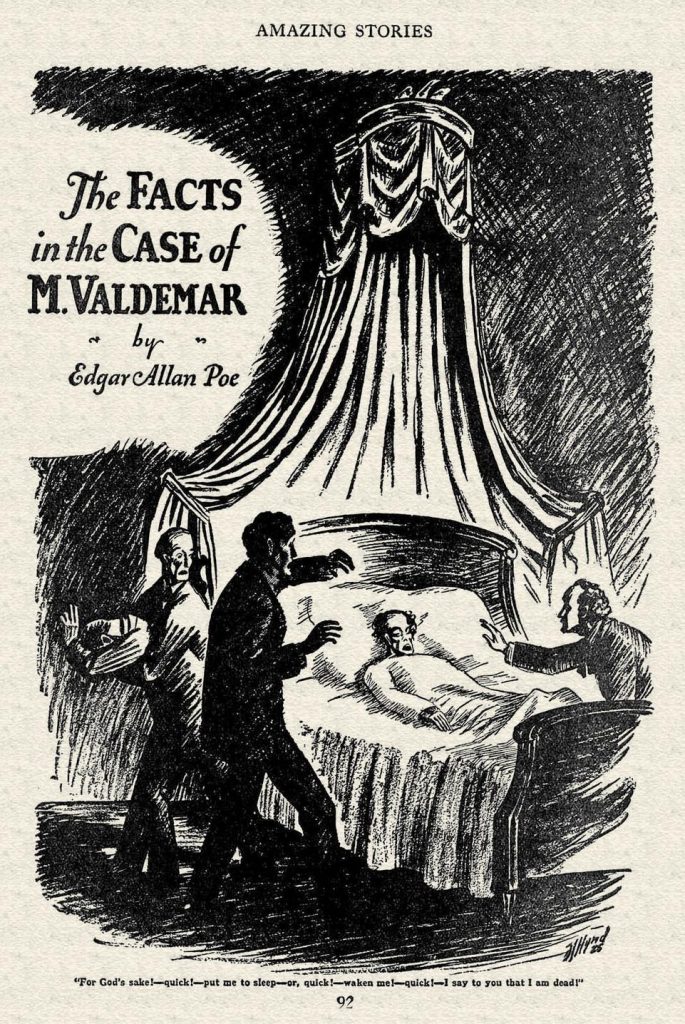

The Facts In the Case of M. Valdemar

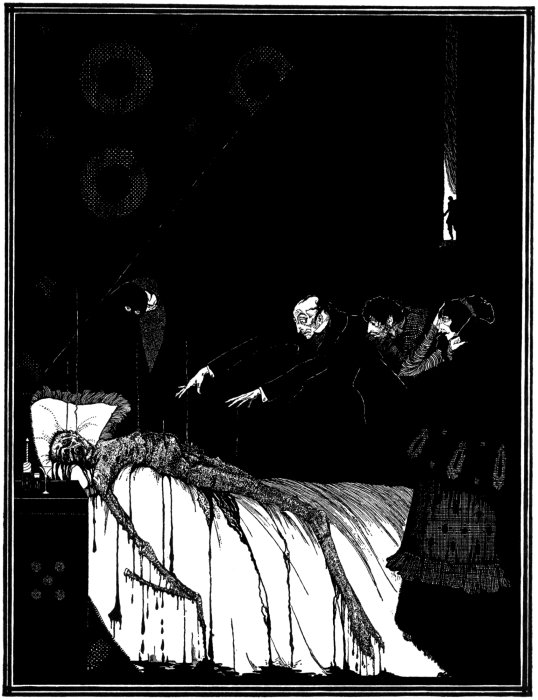

It is very easy to draw a direct line from the dispassionate, scientific tone of this last straightforward horror story to legendary works like At the Mountains of Madness, The Call of Cthulhu, and most significantly, Cool Air. What begins almost like a legalistic recounting of an experiment in the new-at-that-time science of mesmerism (aka, hypnosis) quickly spirals into horror as the experiment’s subject expires, only to be trapped in his own decaying body… for seven months.

The very wet climax, while rushed, remains shockingly gruesome, especially for 1845, and holds up adequately even in this post-splatterpunk era of horror fiction. Poe remains, to this day, a very forward-thinking author. It is almost impossible to imagine stories like the afore-mentioned Cool Air without seeing Valdemar’s fingerprints all over it, and one can easily imagine its after-effects in modern media like the representations of the Walking Dead.

These are only a few of Poe’s works that have been overlooked in today’s world. There are much more worth revisiting, including many poems much more blood-chilling than The Raven… but that is an article for another time.

Until then, if you want to explore Poe a bit more, his works are easily available at any number of online repositories of Poe’s fiction at sites like www.poestories.com, http://www.houseofusher.net/, and http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/25525. I would personally recommend any of the stories highlighted in this article, as well as some other lesser-known classics like The Cask of Amontillado and The Imp of the Perverse. And judges wanting to add a touch of gothic horror to their campaign could do much worse than adding some details from Hop-Frog. Poe, as one can see, offers much to the gamer wanting to explore the origins of Appendix N, as does the subject of a future article, Arthur Machen, whose stories set in the haunted hills of Wales inspired both Lovecraft and Conan creator Robert E. Howard.

Part Three: The Famous Works of Edgar Allen Poe

We all know the titles of his most famous works, but for some, it has been decades since we have actually perused them. So, without further ado, let us take the dust off our English Literature texts, crumple our less-than-fond memories of Poe into a ball, lob them into the nearest trash can, and dive in.

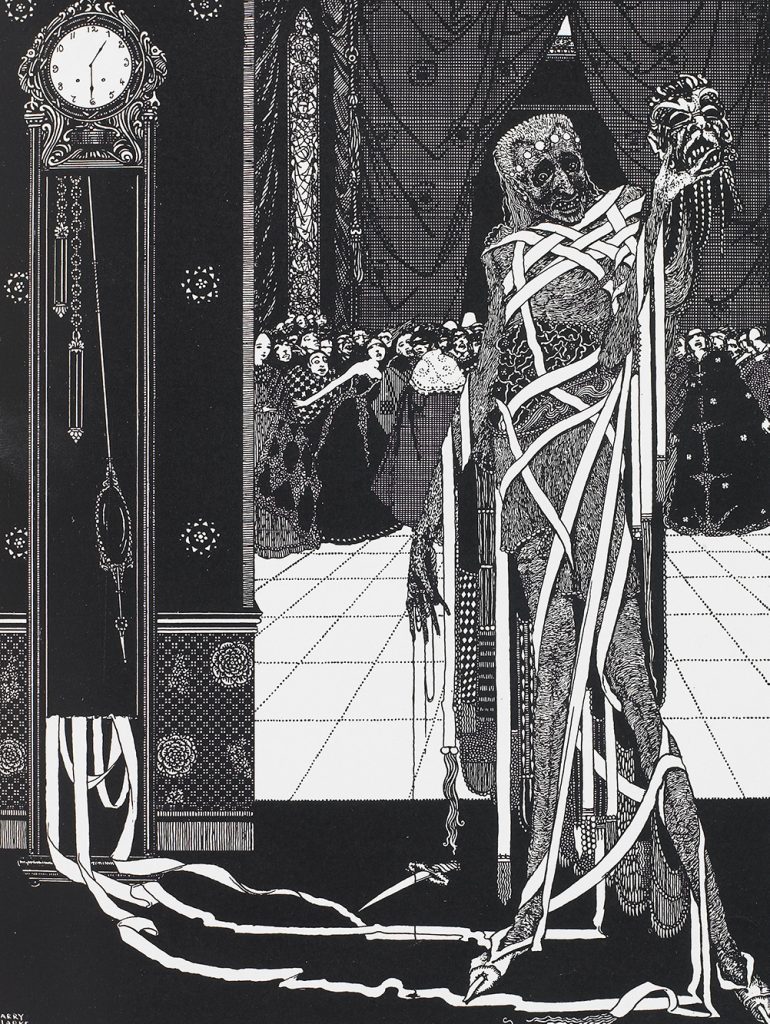

The Masque of the Red Death

This short story from 1842 is simple. During a gruesome plague (the Red Death of the title), Prince Prospero, a decadent nobleman, gathers his closest toadies and retreats to a remote castle to wait it out. To while away the time, he throws a masquerade ball in some morbidly-decorated rooms in the castle, only to find that the avatar of the Red Death has invited itself to the dance, to doleful results. There are precious little character development and no dialogue: Poe concentrates rather on descriptions of the horror of the plague, the rooms, and the events of the masquerade leading up to the chilling final lines.

“And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion overall.”

From a gaming perspective, Masque is a treasure trove. The details of the castle and the descriptions of the rooms is fully realized, and easily adapted to a dungeon setting; the Red Death itself would be an opponent worthy of the climax of an adventure, while Prospero’s followers would provide enough lower-ranked opponents to keep the characters busy as they sneak through the castle (possibly having escaped from the dungeon).

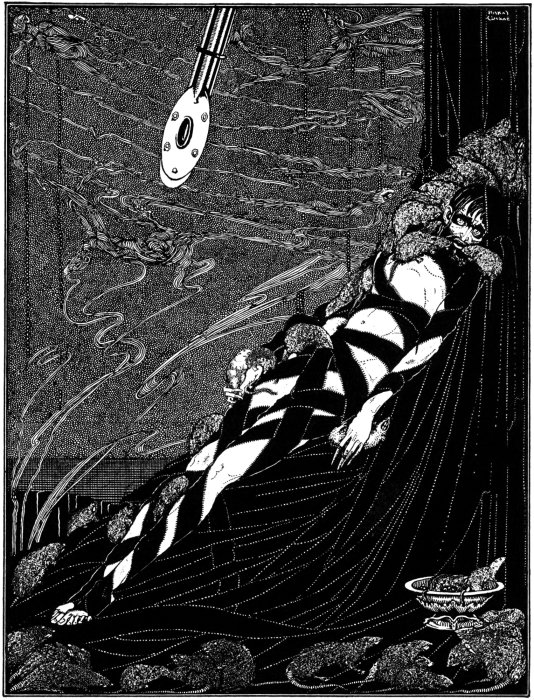

The Pit and the Pendulum

One of Poe’s best-known other works, also from 1842, has a single character: a narrator that has run afoul of the Spanish Inquisition and been imprisoned in a room with absolutely no light. The stream of consciousness of the text as he tries to gain his bearings in the darkness duplicates the panic one would experience at all but be buried alive. The terror of so narrowly avoiding the pit of the title is palpable on the page. His circumstances, once the light is returned, become even direr as the eponymous pendulum makes its slow descent towards the narrator, now bound tight in preparation of the blade slicing him in two.

The entire story reads like a trap from an adventure module… and I would not be shocked to find out that some of the trap rooms from the early days of Dungeons and Dragons were inspired by this story.

The Tell-Tale Heart

Lastly, from 1843, this short story is the least obvious in its influence on gaming, until one actually reads it. In it is the root DNA for every insane monologue from Renfield in Dracula to Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, to every campaign at the eve of its final battle. That is all the story consists of: a rushing tumble of words by a deranged murderer exhorting to the listener how sane and clever he is, even as his words reveal him to be utterly deranged and sloppy in the execution and cover-up of the crime.

From his first mention of “the old man’s vulture eye” to the phantom heartbeat to the climax where he screams for the police to tear up the floorboards where he has hidden the dismembered body, it is a one-way trip into deeper and deeper depths of madness. For any judge wanting to really, really drive home to his players why his main antagonist needs to be stopped, even a light imitation of this story is essential.

There are other stories of Poe’s that could be looked at as influential. These are but three of many. Judges wanting to take to adventure on the high seas could do worse than reading the Narrative of A. Gordon Pym, while any Victorian-era fantasy set in Europe would only benefit from revisiting Murders in the Rue Morgue.

Lastly, like his devotee Lovecraft, Poe understood the power of a snippet of exact information in establishing the credibility of a story or adventure. That credibility is essential to telling a story that stays in the mind, be it written or created communally by a group of players. Poe gifted us with that wisdom, and over 170 years after his death, it is still vital today.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to have a look at our other articles on other Adventures in Fiction authors.