Short Sorcery: Poul Anderson’s “The Tale of Hauk”

by Bill Ward

Poul Anderson, Grand Master of Science Fiction and author of over 100 books, always seems to bring a little something extra to the table when writing a tale invoking Norse mythology. Whether it be in the myth-inspired sword-and-sorcery classic The Broken Sword, or his novelized retellings of the sagas of figures like Hrolf-Kraki and Harald Hardrada, Anderson’s love for the history and culture of the Dark Ages, and in particular the immortal tales of his own Scandinavian ancestors, comes across in every line of these works. “The Tale of Hauk,” the story of a man that must confront the vengeful ghost of his own father, perfectly encapsulates Anderson’s passion for tales of the Viking era, and demonstrates his mastery at bringing such a world to life.

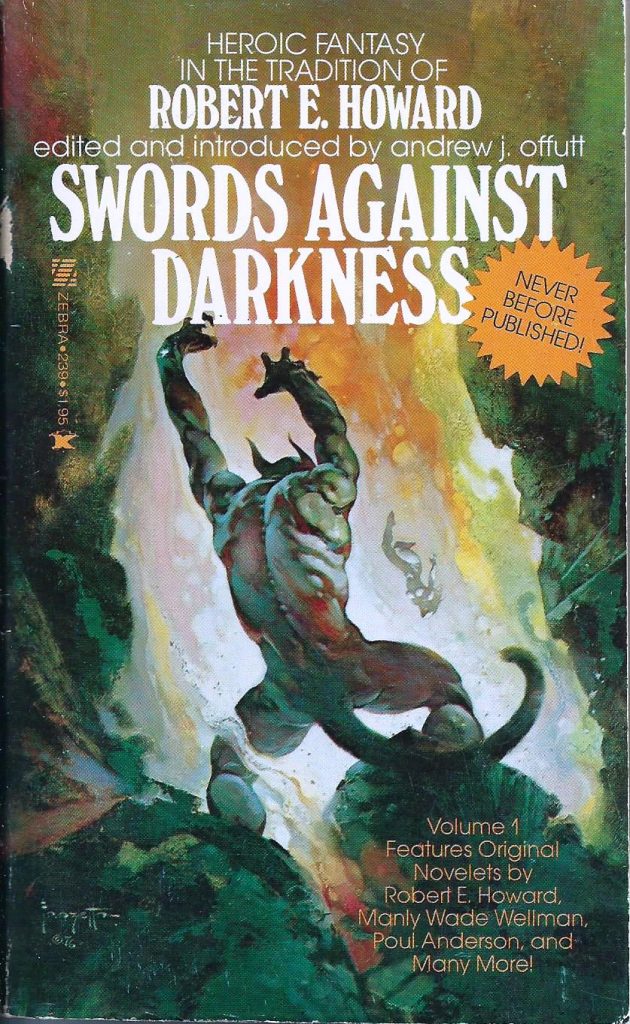

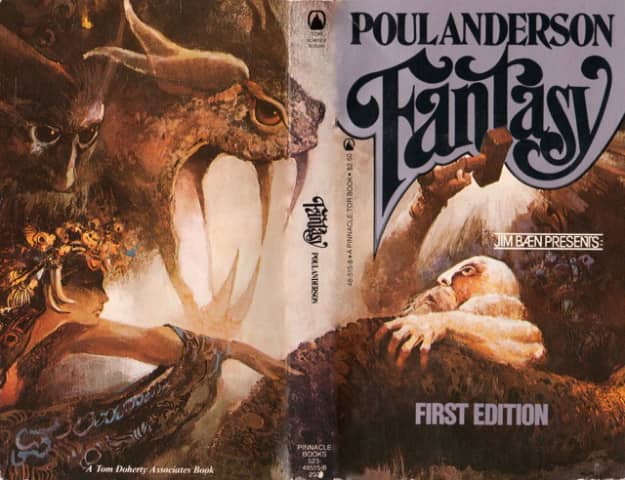

“The Tale of Hauk” originally appeared in the first Swords Against Darkness (1977) anthology edited by Andrew J. Offutt, but has subsequently been reprinted in many ‘Best of’ editions and in Anderson’s own collection, Fantasy. While not strictly sword-and-sorcery in the Howardian sense – Anderson’s own Cappen Varra shorts as seen in the Thieves World shared-world anthologies would be better examples of that – “The Tale of Hauk” is a work of dark, heroic fantasy with a strong splash of Weird Tale. It is also a tour de force of style, written in a way that captures the rhythm and tone of an old Norse saga. On the occasion of Hauk’s homecoming:

“That was on a chill fall noontide. Whitecaps chopped beneath a whistling wind and cast spindrift salty onto lips. Clifftops on either side of the fjord were lost in the mist. Above blew cloud wrack like smoke. Hauk’s ship, a wide-beamed knorr, rolled, pitched, and creaked as it beat its way under sail. The owner stood in the bows, wrapped in a flame-red cloak…”

Anderson uses the short, clipped cadence of the Anglo-Norse tradition, with nary a latinate word in sight. It is direct language, unadorned, in which the nouns and verbs do most of the heavy lifting. In combination with a faintly antique diction in both narrative and dialog, and a finely realized snapshot of North European cultural life of the era of Alfred the Great and Harald Fairhair, “The Tale of Hauk” reads more like a modernized translation of an actual Viking ghost story than a career SF writer’s sale to a sword-and-sorcery anthology:

“Long did the few miles of path seem, and gloomy under the pines. The sun was on the world’s rim when men came out in the open. They looked past fields and barrow down to the empty garth, the fjordside cliffs, the water where the sun lay as half an ember behind a trail of blood. Clouds hurried on a wailing wind through a greenish sky. Cold struck deep. A wolf howled.”

The brooding bleakness of “The Tale of Hauk” is part and parcel of both Norse mythology and a great deal of sword-and-sorcery. Hauk has returned to his home, only to find his father Geirolf grown bitter by the fatal wasting sickness that has robbed him of his strength and shall soon take his life. Geirolf knew success as a raider and reaver, enough to establish his homestead and a great hall for his swordthanes and housefellows, and he mocks his son Hauk’s chosen life as a trader. But Hauk, snapping a stout branch in his powerful hands for emphasis, calmly points out that the men of his own profession must be strongest of all, for they do not prey on the weak, but rather must defend themselves from the war-mad rovers in their dragonships. Before Hauk leaves for the season, his strength and honor have won the love of the daughter of a neighboring garth, but his father’s unchecked rage leads to a confrontation that bloodies Hauk and leaves the two further estranged.

While Hauk is gone, Geirolf dies the hated staw-death; the death in bed of the old and sick, not the battlefield doom that wins a warrior a seat in Valhalla. He is buried, his shade is feasted, and his old dry-rotted longship burned. The hall is quiet for a time as its lord lies beneath the earth, but soon “(t)he moon waxed. On the first night that it rose full, Geirolf came again.”

We soon see that the strong, rolling language of the sagas is just as suited to building a sense of horror and menace as it is to portraying grim combat or painting light and shadow over a chill landscape. Geirolf returns to his steading a draugr – a barrow-wight or revenant – immune to the bite of steel and mindless in his destruction of all life. Barehanded he kills those unfortunates caught outside at night, and harries the great hall until dawn as he stomps astride its roofbeam.

“Geirolf rocked into sight. The mould of the grave clung to him. His eyes stared unblinking, unmoving, blank in the moonlight, out of a gray face whereon the skin crawled. The teeth in his tangled beard were dry. No breath smoked from his nostrils.”

By the time Hauk comes back to confront his father – reluctantly, lest he incur the curse of a father-slayer, but encouraged both by the love of a maiden and a powerful oathtaking – things have grown worse, and his family and their retainers are on the verge of abandoning their home. Hauk, who once brought a werewolf to bay with the power of his bare hands, wrestles the shade of his father and emerges victorious. But this was no unholy act as Hauk feared, but the greatest service – for Geirolf was animated not by hatred, but by a mighty despair at having died abed rather than in clean combat. Hauk, in giving his father the violent, honorable death the old warrior craved, receives his blessing before Geirolf slumps lifeless to his final rest. It is an unambiguously happy ending in a tale so grim, but one that is well-earned by both protagonist and author.

“The Tale of Hauk” is a classic of the genre, and one of Anderson’s finest fantasy short stories. If Snorri Sturluson had ever submitted something to Weird Tales magazine, it might look a lot like this tale of family conflict and supernatural horror. But it was indeed one of our great modern skalds that told this tale afresh, balancing the contemporary literary idiom of genre fiction with the blood and thunder music of the sagas still singing in his veins to craft a first-rate tale of doom and redemption, one as equally at home in the pages of a crumbling dimestore pulp as it would be if chanted in the feast halls of a Norse thane.