Single Terran Scout Seeks Space-Boat: A Look at Jack Vance’s Planet of Adventure Series

by Bill Ward

“A strange rumor has recently reached Zsafathra, to the effect that all men originated on a far planet, much as the Redeemers of Yao aver, and not from a union of the sacred xyxyl bird and the sea-demon Rhadamth. Furthermore, it was told that certain folk from this far planet now wander Old Tschai, performing the most remarkable deeds: defying the Dirdir, defeating the Chasch, persuading the Wankh. A new feeling is abroad across Tschai: the sense that change is on its way. . .” (The Pnume)

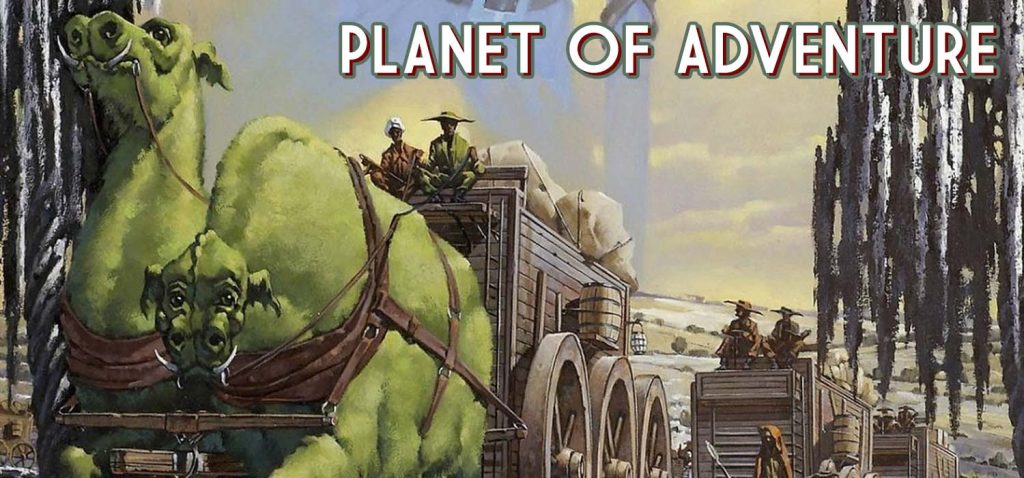

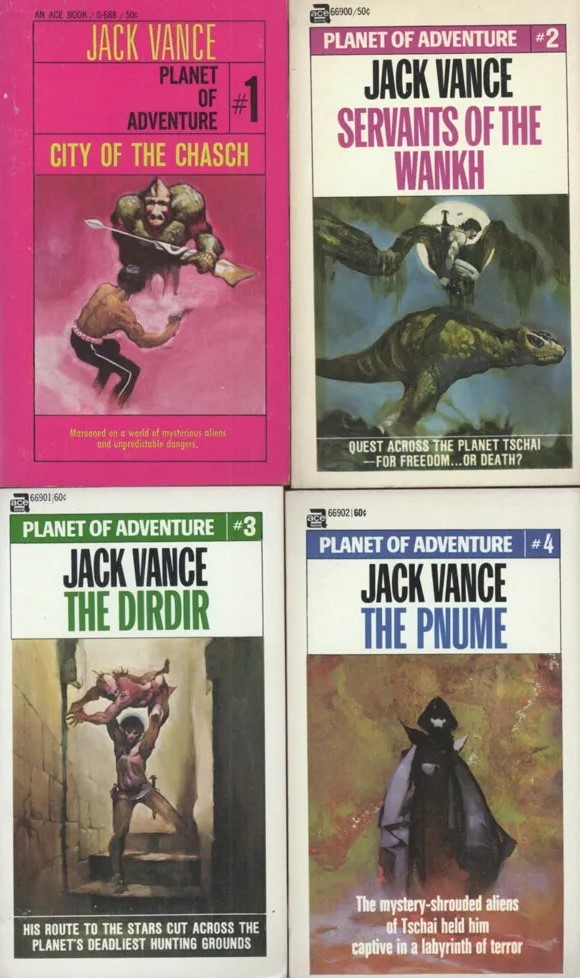

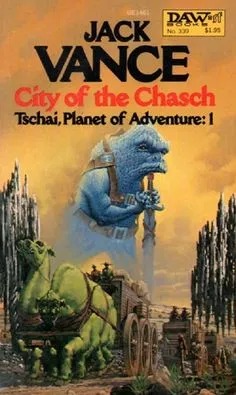

Originally published from 1968 to 1970, Jack Vance’s Planet of Adventure series comprises four lean volumes: City of the Chasch, Servants of the Wankh, The Dirdir, and The Pnume – though it is most readily available these days as a complete omnibus edition (Spatterlight Press offers an ebook entitled Tschai). One of Vance’s most accessible works, it’s often cited by many recommendation lists (including our own) as a great place to start with Vance, or perhaps as the gateway to his science fiction after the reader gets hooked by what is undoubtedly Vance’s most widely known series, The Dying Earth. The closest analog of that saga with Planet of Adventure (and, indeed, with much of Vance’s fiction) would be the tales of Cugel the Clever – tightly-plotted quests through lands of startling imagination and oddness featuring clever reversals and resolutions.

But Adam Reith – hard-driven protagonist of Planet of Adventure – isn’t Cugel the Clever. For a start, he’s not a jerk. A planetary scout attached to an Earth expedition to the distant and unexplored world of Tschai, Reith is an atavism in his own time; a restless, resourceful jack-of-all-trades that doesn’t much fit in on his own homeworld, but is just the sort to thrive in a dangerous, hostile, unknown environment. And it’s a good thing too that he was born for adventure – as soon as his scout boat launches to investigate the mysterious signal sent to Earth from Tschai decades previously, a missile launched from the planet’s surface destroys his interstellar vessel. Crashing on the planet’s surface, he witnesses his partner’s murder at the hands of seemingly primitive and strange human tribesman – the Emblem Men, who soon capture Reith, now the lone survivor of the entire expedition, and acquaint him with some of Tschai’s weird ways.

The Emblem Men wear emblems or badges that are the embodiment of past heroes (and villains) – ’embodiments’ that go far beyond metaphor or emulation, and actually seem to possess the badge-wearers with the personalities of long-dead exemplars. One such possessed individual is the chief of the Emblem Men, a mere youth named Traz, who owes his entire status to his Emblem, rather than his resumé. His people worship the two moons of Tschai, pink Az and blue Braz, celestial avatars of Good and Evil – they even have a catapult to fling the corpses of their fallen toward whichever moon is judged the most fitting repository for their soul. Of course, this isn’t the strangest thing about them (nor are they the strangest humans upon Tschai) – the strangest thing about them is that they are there in the first place.

Reith, during his initial time with the Emblem Men and throughout his journey over this strange world on a quest to find a functioning spacecraft and return to an Earth that has never even heard of Tschai, learns that not only is the planet populated by a myriad of human societies, but that these humans have a history older than the earliest records of mankind’s past. But Tschai, despite teeming with human beings, can hardly be said to be a human world, for it is ruled by four mutually-hostile alien species: the Chasch, the Wankh, the Dirdir, and the planet’s mysterious native intelligences, the Pnume. Each of these alien overlords controls an underclass of humanity, each in their own peculiar and ingenious way. For example, the Blue Chasch (not the Green Chasch, as they have reverted to pure savagery, nor the senescent Old Chasch, long given over to decadence) have convinced their human servitors that humanity is simply the larval stage of Chasch development. Each time a human dies, a little Chasch imp can be found by cracking open the person’s skull – a millennia old smoke-and-mirrors show worthy of the Wizard of Oz. The Chaschmen even wear headpieces and cosmetics to further resemble their alien masters.

In addition to providing a great deal of the setting and theme of the books, the curious alien-human relationships of Planet of Adventure are essential to the structure of the series itself – as a glance at the titles of each installment will no doubt convey. Aliens engineering humans for their own use, or molding them in their own image, is something of a leitmotif in several of Vance’s major works, for example in his classic early novel The Dragon Masters a human population on a far distant world finds itself in a mirrored conflict with a reptilian alien race; the humans have bred the original alien gene-stock into all manner of beasts of burden and beast of war (the titular dragons) . . . and the aliens have done the same to humans. Vance’s Durdane trilogy also features a breed of humans engineered by a hostile alien invader as tools of conquest. Vance delights in depicting strange human societies – in fact I can’t think of a single work of speculative fiction of his that doesn’t – and introducing elements of alien tampering, selective breeding, and cultural domination over thousands of years allows him to imagine even stranger funhouse mirror reflections of humanity.

And here Vance also shows his particular genius when applying his various premises of warped homo sapiens – for the exotic human societies he depicts always retain a core of humanity. In City of the Chasch, Reith’s second companion (after the renegade Emblem Man, Traz) Anacho the Dirdirman, remarks that “men are as plastic as wax” in his smug recitation of Tschai history from the perspective of the Dirdir (who preach that the Primeval Egg split to create the twin races of Dirdir and Human). He goes on to elaborate on the many variations and sub-strains of humanity on the planet, the “dozens of hybrids and freakish races.” But Reith, on the eve of leading a rebellion of outcast humans against their Chasch overlords in the city of Dadiche, notes their underlying humanity as depicted in a scene in a Chaschmen tavern:

“A dozen Chaschmen, faces pinched and twisted under the grotesque false crania, sat hunched over stone pots of liquor, exchanging lewd banter with a small group of Chaschwomen. These wore gowns of black and green; bits of tinsel and ribbon bedizened their false scalps; their pug-noses were painted bright red. A dismal scene, thought Reith; still, it pointed up the essential humanity of the Chaschmen. Here were the universal ingredients of celebration: invigorating drink, gay women, camaraderie. The Chaschman version seemed somewhat leaden and dour …” (City of the Chasch)

Of course, human foibles, flaws, and flavors comprise all manner of behavior – and the gallery of strange-yet-familiar humanity that Reith encounters during his four book adventure over the length and breadth of Tschai are like distillates of an abridged Dickens novel: the ruthlessly acquisitive and personally vile Aila Woudiver, the beautiful Flower of Cath, doomed by societal shame, the mercantile-yet-honorable Zarfo Detwiler, thuggish warlord Naga Goho, naively innocent former Pnumekin Zap 210, or Reith’s own constant companions; unflaggingly dependable Traz, a pure-hearted noble savage, and the effete renegade Dirdirman Ankhe at afram Anacho, source of much of the series’ humor, whose own self-regard exceeded the hierarchical laws of his people, but whose loyalty to and fascination with Reith – and what Reith represents for all of Tschai’s human population – is the source of perhaps the most touchingly genuine relationship in the books.

And there is Adam Reith himself. Universally competent as the great heroes of science fiction’s Golden Age once were, but no superman. In his quest to find a way off planet and back to Earth he is sometimes ruthless as any protagonist in a fast-paced story must be, but never callous. Repeatedly he jeopardizes his mission by doing the morally correct, indeed the genuinely heroic, thing – riding hell-for-leather in a swashbuckling rescue, sacrificing hard-won resources or advantage to do what he knows is right, braving certain doom again and again to save those he loves. His constant example as a strange, yet supremely capable, outsider inspires certain of his fellow humans to see the lie behind alien claims of superiority – in fact, he turns the tables on Chasch, Wankh, Diridr, and Pnume alike, with planet-wide ramifications.

In between the daring-do, Reith engages in various schemes with all the ruthless ingenuity he applies to prison breaks and starship-jacking, Vance’s eloquence and archness of expression rendering the clever exchanges of dialog or careful jockeying for advantage with all the intensity and fascination of a knife-fight. In Planet of Adventure, even the banality of haggling over a spot on a caravan, dealing with usurious middlemen during a construction project, or betting on a rigged eel-race takes on an outsized importance and a vivid color like everything else in Reith’s quest, for as he himself remarks when coming to terms with his predicament “[h]is new life, for all its precariousness, held zest and adventure.” Just like us, Reith is having fun.

And that, ultimately, is what Planet of Adventure is all about – from the perpetual motion machine of the plot and the wild tangle of bizarre alien and even stranger human cultures, to the schemes and reversals, sacrifices and triumphs, the Vancian diction and unique coinages and thousand subtle shrewdnesses of one of the twentieth century’s most unique voices in speculative fiction – it’s all in the service of fun. Sword-and-Planet tropes uptranslated into a Vance-and-Planet frolic: the straight-ahead quest of Planet of Adventure, taken together with its many effortless discursions into the weird-yet-familiar human stew of Tschai’s patchwork of nations, presents a compellingly entertaining series that asserts not only the universality of human nature, but of the universal appeal of narrative adventure itself.