Beyond the Gate of Shadows: Harold Lamb’s The Grand Cham

by Bill Ward

“As evening closed in they were threading through gorges that hastened the coming of darkness. Often they looked back in the failing light. No one desired to be last. And then Rudolfo, in the lead, halted abruptly.

‘Before them in the twilight stood a great mound of human skulls.”

When we are first introduced to Michael Bearn, young Breton ship-master in Venetian employ, he and his shipwrecked crew are slaves to the Turkish Sultan, Bayezid the Great, ‘the Thunderbolt.’ Bearn, talented, headstrong, and proud, refuses to kneel before the conqueror, the ruler of an empire stretching from the Danube to the Euphrates, and Bearn is cruelly cowed when his arm is crushed by an iron sleeve. Crippled, brutalized, Bearn vows his revenge to the Sultan’s laughing face — and thus colossal events are set underway with the snapping of a man’s bones, and the humiliation of his soul. For Bearn is a man of immense drive and cleverness, and Bayezid is not the only great conqueror in the vast lands of the East . . .

Harold Lamb’s The Grand Cham was first published in Adventure Magazine in 1921, and it teeters between long novella and short novel in length. Currently available in the tremendous collection of Lamb’s mostly Crusades-era stories, Swords From the West, The Grand Cham exemplifies much of Lamb’s historical fiction: tight pacing, fidelity to historical authenticity, and a refusal to dwell in stock stereotypes. His fascination with the kaleidoscope tapestry of the people and cultures in this era of clashing civilizations ensures that Lamb breathes real life into his characters even while he thunders ever onward, telling their story in true pulp style – Lamb’s characters feel real enough, they just don’t spend all day telling you their autobiography because they actually have interesting lives to lead and important things to do: such as the making and breaking of history.

Bearn cleverly escapes his Turkish captivity with a handful of his fellow Europeans – all of whom are slain to a man outside the Gate of Shadows, the East-West pass linking the lands of the Sultan with those of Tartary. Bearn, with five more reasons to hate ‘The Thunderbolt,’ has a choice after he buries his companions outside this mountain pass shunned by the followers of the Sultan – go East, into unknown lands rumored to be ruled by the fiercest force out of the steppes since the Great Khan himself, or Northwest, to Trebizond and the Black Sea, and thence back into the European sphere of influence where, perhaps, some power or powers can be aroused to take on the Sultan. He chooses the latter.

Lamb’s chapters in The Grand Cham are stepping stones in and out of the big events of the narrative – most skip ahead in time and space in a way that makes what could be a larger or more convoluted story concise and tightly rendered. In leaping from Bearn as a wandering, lone survivor somewhere in the Caucuses to the next dramatic event in his life, in which he is once again shipmaster to a Venetian crew, this time operating in support at the Battle of Nicopolis, Lamb demonstrates a flair for efficient storytelling in both what he chooses to convey, and what he chooses to ignore. We never see the Battle of Nicopolis, a massive attempt by Western (mostly French) chivalry in conjunction with Hungarian and other central European kingdoms to break the back of the Turkish advance through the Balkans, with the ultimate intended goal to relieve Bayezid’s ongoing siege of Constantinople. Instead, we see the aftermath, the disaster after the disaster, in a chapter that advances the plot, dramatically increases the stakes, and, in a way that the reader hasn’t yet noticed, introduces two more characters central to the story.

From desperate escapes in the East to the rout of crusading armies to the masked intrigues of Venice – Bearn, never flagging from his goal of revenge, is next dueling and sneaking his way around the city of canals and commerce, and it is here that the rest of the stage for this story is set. Rudolfo, venal nobleman and cowardly condottiere (Bearn witnessed him striking his own retainers in a bid to flee Nicopolis for Bearn’s own ship) emerges as the treacherous foil for our protagonist. Bembo, a sardonic jester abused for his stature, is saved by Bearn and becomes his constant companion – as well as the source of the tale’s ultimate punchline. And there is Clavijo, a great traveler to far Eastern lands, a brave explorer who has come back from the long road once trod by Marco Polo with fabulous stories of the ruler of Far Cathay, the so-called Grand Cham, Monarch of the East. Clavijo’s tales whet the appetites of the Venetian Maritime Council, who sponsor a sea voyage to attempt to establish trade relations with this wealthy kingdom – a potentially vital commercial lifeline in a Mediterranean world rapidly falling under Turkish sway.

Except, of course, Clavijo is a liar. Bearn himself saw Clavijo – a fat Spanish merchant – fleeing the chaos of Nicopolis just as he had witnessed Rudolfo do the same. Herein is the reliance on coincidence for pulp-pacing – however, Lamb never uses such circumstance to cheat his way out of a resolution or to propel the actual bones of his plot forward. It is done for efficiency, and it is done well – we don’t know either of those characters when we first meet them, but Bearn’s impression of them sticks with us and, when we are reintroduced to them formally in subsequent chapters, we already share Bearn’s secret knowledge of them – and his opinion of them as well.

“Was there no power on Earth that could match the Thunderbolt?” Bearn is left wondering after Nicopolis. In escaping the Near East, he had fled homeward to his own people, hoping there to find the instrument of his vengeance. Now, with the ‘crusader’ army annihilated, Bearn can think of only one other possibility – the ruler of Tartary. Not the ‘Grand Sham’ (or ‘Great Con!’) of Clavijo’s bedtime stories, but the Khan of Samarkand, the most potent warlord since Genghis, Timur the Lame, or Tamerlane as he has become known in the Western tradition. Somehow, Bearn would have to go back, to cross the Gate of Shadows, and win the support of the Horde of Tartary.

And so the story unfolds. Bearn gets himself appointed shipmaster to an expedition with the avowed goal of seeking a tall tale – but Bearn knows that the kernel of truth contained in Clavijo’s fancies can lead him to the one power on Earth that can enact his revenge. Accompanied by Rudolfo, who despises and undermines Bearn at every turn, and Bembo his loyal friend, the expedition practically retraces Bearn’s earlier journey, only this time going deeper into the East. How exactly Bearn arranges for his vengeance is part of the fun of the story, but the culminating scene of his plan, in which he sits across from Tamerlane at the latter’s massive triple-wide Persian Chessboard and conveys the dispositions of Bayezid’s defenses prior to the Battle of Ankara is as memorable as it is ingenious.

The Grand Cham comes full circle with the climactic Battle of Ankara, the entire narrative nicely mirrored by multiple geographic and thematic bookends that highlight how structurally deliberate Lamb’s pacing is, even while the action just whips along in compelling, page-turning style. His characteristic fidelity to historical authenticity permeates the whole – one aspect of the story that is practically a minor theme of the piece is Bearn’s status as a commoner eliciting contempt from both Christian and Moslem nobility* – and Lamb’s refusal to do stock villains ensures that, not only does his fiction feel more realistic, but it also possesses a capacity for surprise. For all Lamb’s adherence to magazine pacing, he by and large lets his character’s motivations drive much of the action forward, and this is something Howard Andrew Jones highlights in his introduction to The Grand Cham in its standalone publication for Wildside Press.

But in the end it is History that is Lamb’s great character, and his ability to weave his own fiction through and around the great events, conflicts, and peoples of the past is perhaps unmatched, certainly in comparison to other authors writing pulp adventure for fast-turnover magazine publication. A story like The Grand Cham works whether it is a reader’s introduction to these epoch-making events, or if one reads it with the certainty of foreknowledge, in both cases Lamb’s tale is structured to be rewarding for any audience. And, like with all the best pulp fiction, whether fantasy and science fiction or hardboiled detective or historical or horror, Lamb’s work is deep enough that it rewards revisiting, exhibiting that timeless quality far outlasting both the publishing philosophy and the literal paper stock, of the age in which it was written.

*Also, it is interesting to note that the only two characters to really respect Bearn for who he is are themselves crippled or maimed in some way – just as Bearn himself is crippled by his crushed right arm.

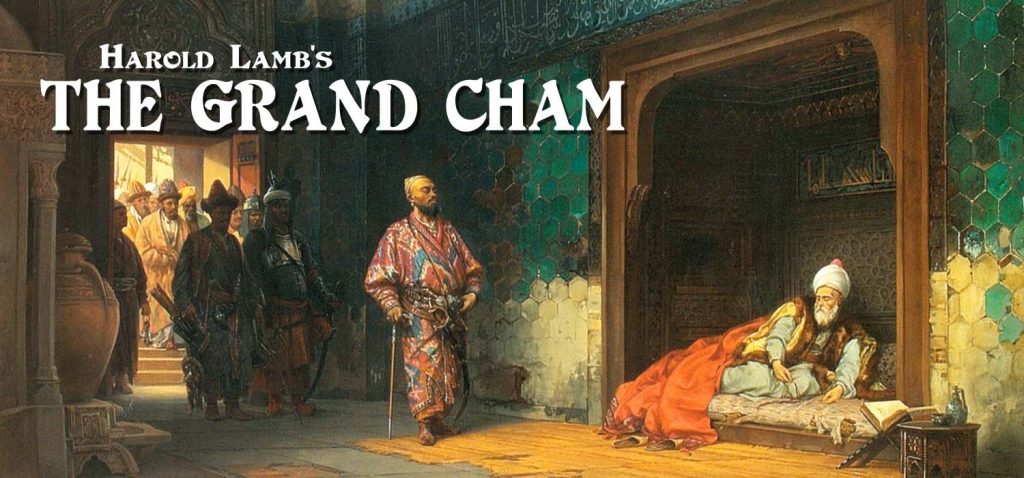

The header image for this essay is ‘Sultan Bayezid as Prisoner of Tamerlane’ by Stanislaus von Chlebowski (1835-84)