My Favorite Solomon Kane Tale: “Wings in the Night” by Robert E. Howard

by Fletcher Vredenburgh

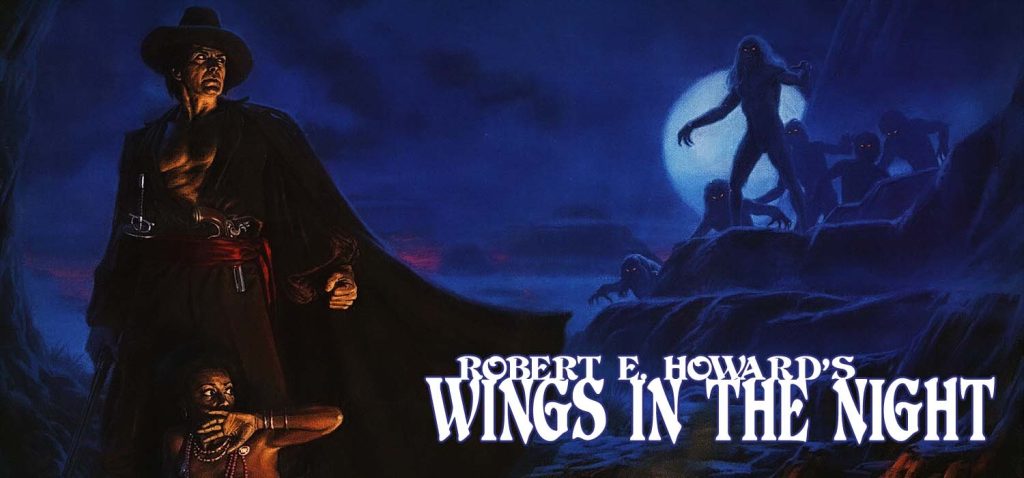

“Wings in the Night” (1932), is one of Solomon Kane’s, Robert E. Howard’s swashbuckling Puritan, African adventures. In the face of darkness, he sees himself as Satan’s implacable foe. Kane’s a dour man, dedicated wholly to defeating evil and meting out justice. In two separate stories, he spends years hunting for the killers of innocents. A skilled swordsman, he has freebooted in the New World, suffered at the hand of the Inquisition, and fought vampires and cannibals in Africa. In this story, he battles great bat-winged, razor-taloned monsters.

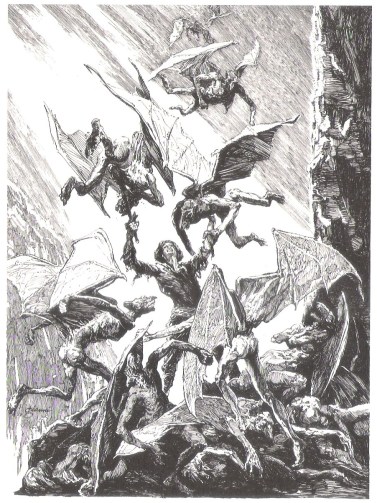

This story is one of REH’s most visceral, and blood is spilled on every other page. Also, it’s one of my favorites. As it opens, Kane is fleeing from a band of cannibals when he discovers a devastated village and within it, a mutilated, yet still living man, tied to a stake. The village appears to have been attacked from above. One body hangs high up in a tree, impaled upon a branch. Continuing to evade his pursuers, he finds himself set upon by a winged creature with a manlike face.

He barely survives that encounter, thanks only to the ministrations of people from the village of Upper Bogonda. That town has long been subject to the bloody depredations of a tribe of winged monsters. Seeing that Kane killed one of the creatures, they look to him for protection. Denying any of the divine power they perceive in him, as well as any real hope he can defend them, he pledges to stay with them nonetheless: “Yet will I stay here in Bogonda all the rest of my life if ye think I be protection to the people.” It’s an effort that ends in failure and madness.

“Wings” is bloody and savage, more so than any other of Howard’s stories that come to mind. It shares with the Conan story, “Beyond the Black River,” a sense of inevitable doom, but it’s far darker. That story revolves around colonists facing off against the indigenous tribes; here, villagers forlornly await their fates at the claws of sadistic creatures who view them as little more than cattle. Hundreds of innocents are torn apart, decapitated, or eaten alive. In the end, they all end up in the monsters’ bellies and Kane is a screaming madman. Kane may avenge the Bogondans, it does them no good and he’s still mad.

He threw back his head to shriek his hate at the fiends above him and he felt warm, thick drops fall into his face, while the shadowy skies were filled with the screams of agony and the laughter of monsters. And Kane’s last vestige of reason snapped as the sounds of that ghastly feast in the skies filled the night and the blood that rained from the stars fell into his face. He gibbered to and fro, screaming chaotic blasphemies.

And was he not a symbol of Man, staggering among the tooth-marked bones and severed grinning heads of humans, brandishing a futile ax, and screaming incoherent hate at the grisly, winged shapes of Night that make him their prey, chuckling in demoniac triumph above him and dripping into his mad eyes the pitiful blood of their human victims?

The story is a gripping, propulsive read that shows Howard’s writing at its best. Before hitting the reader with monsteriffic action, he pulls you in with mystery and horror; who destroyed the village and why was the man bound to the post? At the same time, there’s the implicit fear of the pursuing cannibals. From the first paragraphs, Howard starts building tension and keeps ratcheting it up until it has to explode. When the action comes, it’s swift and sharp:

The winged man had wrapped his limbs about the Englishman’s legs and the talons he had driven into Kane’s breast muscles held like fanged vices. The wolf-like fangs drove at Kane’s throat, but the Puritan gripped the bony throat and thrust back the grisly head, while with his right hand he strove to draw his dirk. The birdman was mounting slowly and a fleeting glance showed Kane that they were already high above the trees. The Englishman did not hope to survive this battle in the sky, for even if he slew his foe, he would be dashed to death in the fall. But with the innate ferocity of the fighting man he set himself grimly to take his captor with him.

“Wings in the Night” also displays Howard’s ease at world- and myth-building. The Bogondan priest, Goru, tells Kane the tragic tale of how his people came to be the flying monsters and the cannibals. At the same time, his story triggers in Kane an idea that the monsters might have links to even older stories reaching back to older legends from beyond the African shores. We also learn some of Kane’s bloody past. The story doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but, instead, reads like a chapter from some longer work, set in a larger world of shadows and dangers that stretch far beyond the boundaries of its fifty pages. (Which, of course, is true – REH published five other Kane stories in his lifetime)

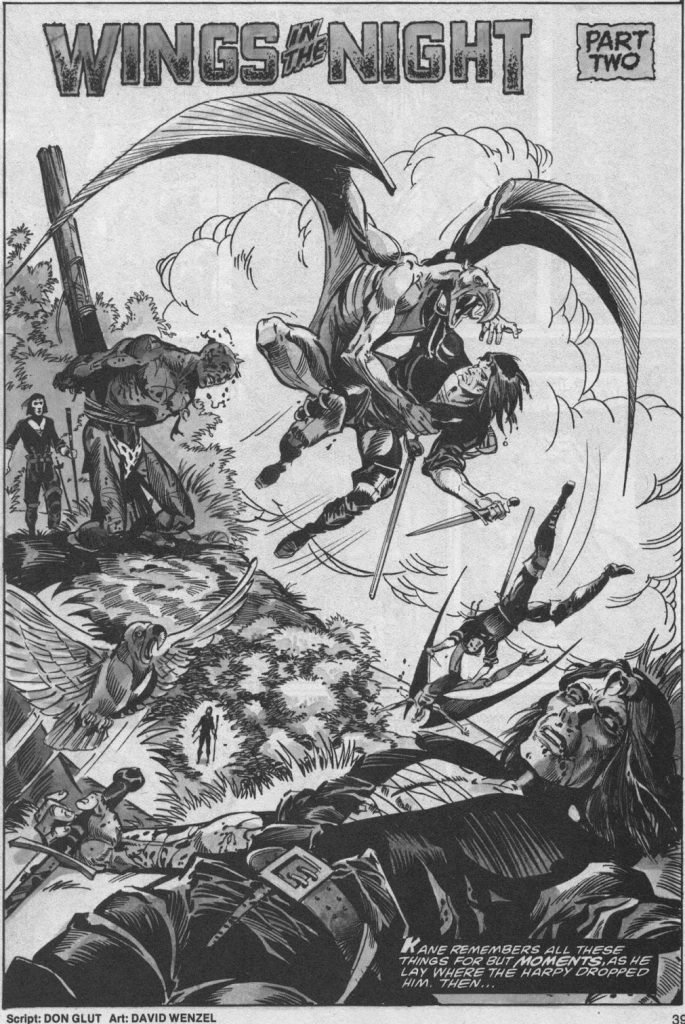

My first encounter with Solomon Kane wasn’t with one of the actual stories but in a comic book version. I picked up a small stack of The Savage Sword of Conan at a street fair. The Conan stories didn’t do much for me – I’m just not a fan of fur-loinclothed Conan – but in the back of issues 53 and 54 was something that grabbed me: writer Don Glut and artist David Wenzel’s adaptation of “Wings in the Night.” It was gruesome and violent, and that was enough for me.

It was only when I picked up copies of the Bantam Solomon Kane collections, The Hills of the Dead, did I read Howard’s own words. If the comic had impressed me, the real story gutted me. And it still does. Along with blood and thunder, the story has a brutal emotional core. If, somehow, you have missed out on Solomon Kane’s adventures, get thee hence at once to a book-selling establishment.