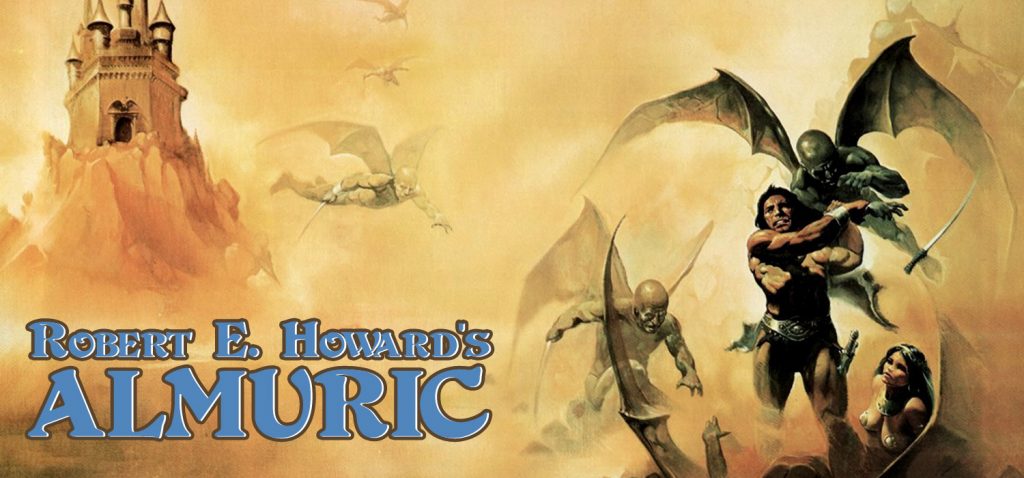

Sword and Planet as Blood and Thunder: Robert E. Howard’s Almuric

by Bill Ward

“’Lead us to Yugga, Esau Ironhand!’ cried Than Swordswinger. ‘Lead us to Yagg, or lead us to Hell! We will stain the waters of Yogh with blood, and the Yagas will speak of us with shudders for ten thousand times a thousand years!’” —Almuric, Robert E. Howard

Robert E. Howard is a member of that select group of authors whose very name has become adjectival – a Howardian story is violent, two-fisted adventure in which theme and forward motion are paramount, outsider heroes are fierce yet noble, and physical and mental toughness represent the highest virtues. Howard’s own stories are also rollicking good escapist fiction written with more ingenuity and care than much that was produced by his imitators, even when he, himself, was laboring in another’s shadow. Almuric, Howard’s posthumously published short planetary adventure novel, is a great example of this. Though it is clearly charging headlong down the well-trodden path of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars books, Almuric doesn’t read like Burroughs pastiche, indeed it goes beyond even the somewhat apt-but-too-pat ‘Conan on Barsoom’ tagline to stand apart as its own thing: Howardian sword-and-planet.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: extraordinarily capable loner misfit warrior fleeing certain destruction miraculously escapes to colorful planet of adventure and ascends to benign dominance by virtue of his prowess and essential decency. It’s of course A Princess of Mars and the dozens of science fantasy books that pay homage to it but, reshuffle or remove a few of the elements, say the radium pistols, the six-limbed Tharks, and the crimson-skinned beauties, and you’ve more-or-less got another Burroughs classic, Tarzan. But it’s even bigger than those, it’s the modern uber-myth of the nineteenth and twentieth century West, it’s everything from King Solomon’s Mines to T. E. Lawrence, Robinson Crusoe to Gordon of Khartoum. Until the zombie apocalypse replaced it, it was the dominant modern myth, and the baseline of much of adventure fiction – the capable modern man testing his mettle in a part of the world, or solar system, to which he was not native.

“The average civilized man is never fully alive … Life flickers feebly in him; his senses are dull and torpid. In developing his intellect he has sacrificed far more than he realizes.” Meet Esau Cairn, “the most perfectly developed man on Earth,” a man not merely at odds with his time, but “born outside his epoch.” If John Carter’s superpower is a musculature developed in Earth-normal gravity, Esau Cairn’s is that he is an atavism – a man stronger, fiercer, faster, and more rageful than the normal members of the civilization he was born into. It’s not enough to say Esau Cairn is a man’s man, he’s Cro-Magnon man’s man.

He is also among the most Howardian of heroes. While John Carter evades an Apache war party, Cairn flees a corrupt and unjust system, having been used by venal politicos until he got wind of the deception and broke a villain’s skull with his fist. Like Carter among the Tharks, Cairn achieves respect and authority among the Guras, but only after he has first endured a period of total primitivism. Arriving on the fabulous world of Almuric in about as convincing a way as Carter is transported to Barsoom, Cairn beats the first man he meets unconscious over an insult and retreats to the wilds, to undergo a savage purification.

“I was living the life of the most primitive savage; I had neither companionship, books, clothing, nor any of the things which go to make up civilization.” Nor, indeed, at this point does Cairn even have fire – he gulps his meat raw, and gathers a bounty of fruit and nuts from the Almurician countryside. He is hardened by privation, exposure, and constant danger. He finds himself in a world something like the African savanna, where he must compete with dangerous fauna analogous to beasts we are familiar with: hyenas, bears, giant boars, and sabertooth cats. His only tool is a knife taken off the first Gura, a ferocious apelike man, he meets within moments of appearing on Almuric. And for the reader, that Gura, and a few other oddities offhandedly mentioned in the narrative, are the only hints we get – at this stage — of the kind of sense of wonder weirdness one expects from this kind of fiction. While Burroughs blasts the audience with a ‘we’re not in Kansas anymore’ scene as soon as his hero sets foot on extraterrestrial soil, Howard may as well have transported Cairn to a remote part of our own world, or back in time to the neolithic.

Which serves the theme of Almuric very well – this is not just about a picaresque adventure through a land of fabulous adventure, it’s about Howard’s own great subject and fixation, the freedom of the natural life, the triumph of the barbarian. It’s escapist, but so is Burroughs and every other pulp writer. It’s an unrealistic portrait of noble savages possessed of a tiger’s ferocity and a schoolboy’s diffidence toward woman, but that’s because no one would be entertained by the truly barbaric presented in all of its ugly wholeness. And Howard isn’t wrong when he points out the faults of the civilized, his view, Cairn’s view, Conan’s view, isn’t naive because it’s idealized, any more than the sins of the savage disprove his virtues – or excuse those of modern man.

If Cairn could be said to have a sin it would be pride – he’s reminiscent of Conan in the Maul of Zamora, content to turn away from conflict until his person is mishandled, and then he’s transformed into an avatar of murder. Cairn himself is perfectly agreeable until insulted or interfered with, in fact the first person, or Gura, he meets unknowingly insults Cairn by asking if he’s a woman, and the two come to violent blows. It’s the first of many battles in Almuric, and it sets up not only a villain that will return to haunt Cairn later, but hints at the unusual sexual dimorphism of the Guras themselves – the men of their race are shaggy, apelike, and brutish, whereas their woman are indistinguishable from those of Earth, save being even more beautiful and less independent. Imagine a Planet of the Apes where Nova is the daughter of Dr. Zaius.

Of course, the Guras have nothing like Orangutan theologian-scientists in their midst – their material culture is simple and wholly practical, their society static, an “exuberant barbarism” and rigidly hierarchical, geared wholly for hunting and war. They possess the same touchy honor that Cairn has, and regardless of whether it stems from the code of the Southern Gentleman or the interpersonal agon of the Homeric heroes, it is a Howard staple. They are crude, brutal, but mostly without malice or scheming, and universally chivalrous when it comes to protecting their lady-folk. Guras are Noble Savages, one part ferocious apeman, the other part demurring damsel. Cairn has found not only a perfect world to test his mettle, but a perfect people to call his own.

This is all the stuff of wish fulfillment fantasy, the sort of thing that lesser authors can’t handle for fear of embarrassment, but that nevertheless beats strongly at the heart of the best pulp fiction – or Medieval lay, or Ancient Epic, or legend from the dawn of time. Cairn’s strength, persistence, and heroism see him adopted by a Gura tribe; that plus his no doubt boyish good looks and stranger’s exoticism wins him the heart of Altha, a beautiful Gura lass who is a bit of a mirror of Cairn, having something more akin to “Earthlike” sensibilities in much the same way that Cairn himself seems more of a natural fit for Almuric. She, of course, gets captured — not once but thrice – and Cairn flys (literally) to the rescue.

The Yagas are the weird menace of the piece, a wickedly evil race of bat-winged flying humanoids that prey upon all of the peoples of Almuric. They capture Altha, and Cairn too, and take them to “the black citadel of Yugga, on the rock Yuthla, by the river Yogh, in the land of Yagg.” The language rolls biblical, the villains themselves are demonic – and civilized. Their fortress is alive with the screams of their slaves as the black-hearted, cannibalistic Yagas devise tortures and depravities to banish the ennui of their empty days. Yasmeena, their Queen, possesses the cruel perfect “beauty of a soulless statue,” and she keeps Cairn in golden chains, fascinated by her new plaything, a man like no other she has ever seen. She asks him about the beliefs of the Guras, and scoffs at their notions of Valhalla:

“Stupid pigs. Death is oblivion. We Yagas worship only our own bodies. And to our bodies we make rich sacrifices with the bodies of the foolish little people.” You don’t have to travel as far as Almuric to hear echoes of such nihilism in our own world, the dark inversion of the healthy physicality of the barbarian. Cairn, for all his power and physical perfection, is tempered by a noble and caring soul. The Yagas are purely materialistic, architects of a “thousand ages of cruelty and oppression,” and value both power and cruelty for its own sake. They even clip the wings of their woman at birth, their impulse to control the flip-side of the Gura’s impulse to protect their wives and daughters behind cyclopean walls of green stone. Only the Yaga Queens, most wicked and terrible of all, retain the ability to fly.

Yasmeena’s temptation of Cairn fails, and our hero escapes to lead the united clans of Guras in a climactic castle-storming that rescues the slaves of the Yagas, among them Cairn’s love Altha, and breaks the cruel reign of the winged men forever. It’s a perfect blood and thunder final act to a pulp engine of invention that had been racing along since the first scene. Certainly, some of the excesses of pulp fiction, the hasty writing and purple prose, the formula, the too-convenient or too-coincidental plot elements can be found in Almuric, and anyone that wants to make issues with these can happily shoot fish in a barrel all they like. But, in our own modern parlance, I’d argue many of these things are a feature, not a bug. In the hands of someone of less skill, the flaws stand out – in the hands of a master, the flaws only serve to reinforce the aesthetic of the whole. Robert E. Howard certainly was a master of telling stories that people want to be immersed in, of pounding out a pace that rushes forward with a kind of surefooted near-recklessness toward a satisfying catharsis, and of putting his own Howardian stamp on everything he touched.

But, and there’s a but, how much of Almuric is actually Howard’s work? The novel was originally serialized in Weird Tales for posthumous publication and it was based on a combination of unfinished drafts. It did always seem strange that Cairn intended to “instill some of the culture of my native planet into this erstwhile savage people” at the rather too-happily-ever-after close of the story. Isn’t the culture of his native world exactly what Cairn was at odds with? And the breathless climax of the novel is where things start to feel slap-dash at times, although still presented in a coherent and terrifically explosive scene. Were these passages simply fleshed out from a sketchy outline by Howard, perhaps by Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright himself? The question of who finished Howard’s draft is probably not one that will ever have a definitive answer; most have assumed it was Otis Adelbert Kline, Howard’s agent and literary executor, himself an author of adventure fiction and several sword-and-planet novels (The Swordsman of Mars). Howard scholar Morgan Holmes suggests the prolific Otto Binder as the most likely candidate in his article “The First Posthumous Collaborator” in the Dec 2008 issue of The Cimmerian.

So perhaps some of those flaws in Almuric really have more to do with it not being properly finished and polished over by Howard himself, which only serves to further tantalize fans who’d like to think of all those lost wonders he might have lived to produce. But what is here, the brutal fast-paced action, the outsider more at home among beasts and brawlers, the sinister nature of organized power, is pure Howard, even if it doesn’t always live up to the best of his output.