Where to Start With Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane

by Brian Murphy

His visitor was not a reassuring figure. At rather more than twice the thin man’s bulk, he sprawled half out of the room’s single chair. His massive frame exuded an aura of almost bestial strength. The figure might have been that of some great ape, clad in black leather trousers and sleeveless vest. Ruthless intelligence showed in the brutal face, framed by nape-length red hair and a beard like rust. A red silk scarf encircled his thick neck, and belted across the barrel chest, the hilt of a Carsultyal sword protruded over his right shoulder. The savage blue eyes held a note in their stare that promised sudden carnage should that huge left hand reach for the hilt.

–Description of Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, Dark Crusade

Sword-and-sorcery “heroes” are typically not that—not the two-dimensional protectors of freedom in colorful tights with which we associate the term “hero” today. The two best thieves in Lankhmar were not out to save the world, but to line their pockets and bed women. Conan ascended the throne of Aquilonia, but it was no coronation of the latest in the line of destined kings, but rather the arrival of a red-handed barbarian who spent most of his days as a rogue, a mercenary, a pirate, and a Cossack, carving a bloody swathe to a kingship with an ill-fitting crown.

Dark of nature and enigmatic of motive, the red-headed, blue-eyed, immortal Kane, the creation of the pen of Karl Edward Wagner (1945-1994), is very much cut from this same cloth. Kane is the rumored Cain of the Hebrew bible, cursed by his creator for some ancient transgression. This aspect of his identity is hinted at in the stories rather than explicitly stated, which adds to his general coolness and mystery.

While Kane lacks a traditional morality, he’s not a serial killer or sadist, but a mercenary. Wagner does a skillful job rendering him identifiable and human, just sympathetic enough to earn our rooting interest (in most stories—in some he’s a real bastard). Just don’t call him an “anti-hero”—Wagner despised the term.

Kane carries the curse of immortality, although he can be slain by violence. He wanders the earth seeking escape from his ennui and the inevitable separation from earthy relationships and loves, whom he outlives. In other stories he plots for power and wealth, either to satiate his suffering or carve out an empire where he can amuse himself.

Some have categorized the Kane stories as dark fantasy, others as science fiction. I consider them sword-and-sorcery, but recognize that your mileage may vary. Wagner himself preferred epic fantasy or dark fantasy, and once complained that sword and sorcery “conjures an image of yarns about girls in brass bras who are in constant danger of losing them, and mighty warriors with eighteen-foot-long swords killing wizards and monsters faster than thought.” Anyone who’s read enough S&S must admit this does describe a wide swath of the subgenre. Fortunately, the Kane stories transcend formula and the worst of its cliches. Wagner understood its conventions and used them, occasionally taking the piss out of them (as he did in “Undertow,” which skewers the barbarian stereotype).

Wagner was deeply versed in the traditions of pulp fantasy and his love of the genre was apparent. He edited Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories in a three volume set published by Berkley Medallion in 1977. These restored Howard’s texts from the Weird Tales originals, boasted gorgeous fold-out posters by the great Ken Kelly, and remain worth tracking down for Wagner’s erudite and barbed introductions. He was not a fan of L. Sprague de Camp’s heavy-handed editorial treatments of Howard, though he did himself write Howard pastiche including the Conan novel The Road of Kings. Before his untimely death in 1994 Wagner returned to sword-and-sorcery with the short-lived series Echoes of Valor, which in three volumes republished more Howard alongside the likes of Fritz Leiber, C.L. Moore, Manly Wade Wellman, and Henry Kuttner.

Although Wagner discovered Howard after conceiving of the character of Kane, he was deeply influenced by pulp fantasists including the likes of Wellman, Moore, Leiber, H.P. Lovecraft, and Michael Moorcock. Wagner later came to love Howard, in particular the Atlantean King Kull, whose brooding, philosophical mien describes something of Kane, as does Solomon Kane.

Wagner was also a student and aficionado of horror—his contributions to the field as author and editor of the long-running Year’s Best Horror Stories anthology are considerable—and so a strong horror sensibility and Gothic atmosphere infuse the Kane stories. “Reflections for the Winter of My Soul” for example is a werewolf murder-mystery that happens to have Kane in it.

So, if this all sounds sufficiently interesting, where to start with Kane?

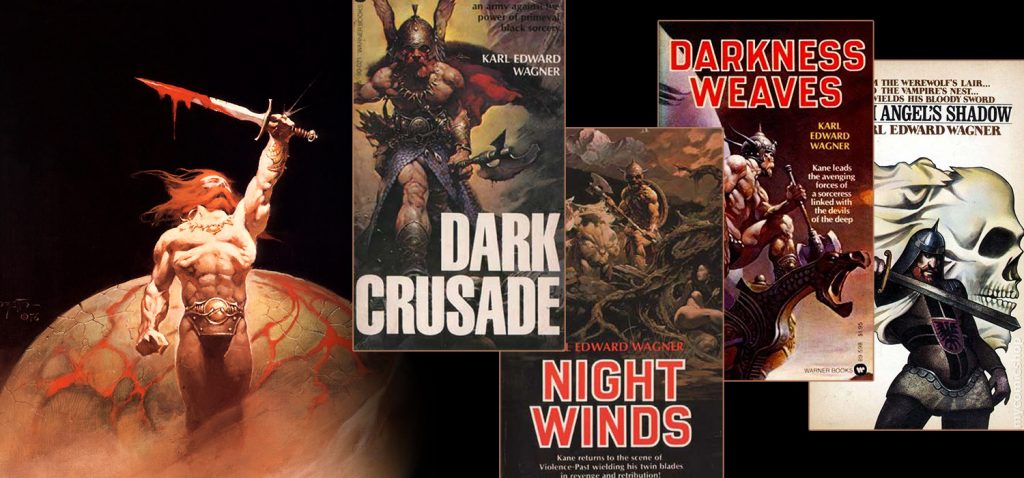

If I had to narrow it down to one book, I’d probably go with the collection Night Winds, which contains a very nice selection including “Undertow,” “Two Suns Setting,” “The Dark Muse,” “Raven’s Eyrie,” “Lynortis Reprise,” and “Sing a Last Song of Valdese.” Reading these half-dozen Kane stories should be enough to determine if you want to press on to the novels, including the grim Dark Crusade, the classic Darkness Weaves, or the utter gonzo craziness of Bloodstone. Unfortunately Night Winds does not contain probably my favorite Kane story, “Cold Light,” which can be found in the collection Death Angel’s Shadow.

Where to really start with Kane is, unfortunately, with a struggle to get ahold of the stories, and a decision to pursue print vs. digital. Fortunately the Kane stories are now cheaply available as e-books, but unless you own a Kindle (I don’t), you’ll have to scour the second-hand market for print. Until recently a mass-market paperback line from Warner Books were pretty reasonable, about $6-10 on average, but now seem to be fetching between $19-25 a copy. Forget about the Centipede Press editions, unless you are independently wealthy and willing to shell out $180, and up.

I read in print almost exclusively (any device with an internet browser offers too much distraction) so I’d personally recommend hunting up the Warners. And then, hounding the Karl Edward Wagner estate to publish the Kane stories in something like a handsome three-volume trade paperback edition, similar to what we now have with the Del Rey Howards. The Kane stories are simply too good to be languishing as they are, and I envy those coming to them for the first time.

Brian Murphy (born 1973) discovered Robert E. Howard in the pages of Savage Sword of Conan in the early 1980s, sparking a lifelong love of fantasy. He went on to read widely in fantasy and science fiction before discovering his true passion lay in sword-and-sorcery fiction.

Murphy started writing about fantasy on the web in 2007 and was recruited to join a group of bloggers at the Cimmerian, a website dedicated to Howard, J.R.R. Tolkien, and heroic fantasy. Since then he has been published in numerous print publications and online venues, including the Cimmerian, Black Gate, Mythprint, REH: Two-Gun Raconteur, The Dark Man, DMR blog, Skelos, and SFFaudio.com. Murphy’s essay “The Unnatural City” (from the Cimmerian, Vol. 5 No. 2) was nominated for Outstanding Achievement—Essay at the first annual Robert E. Howard Foundation awards in 2009, as was his “Unmasking ‘The Shadow Kingdom’: Kull and Howard as Outsiders” (from REH: Two-Gun Raconteur #14) in 2011. In 2020 his first book, Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery, was published by Pulp Hero Press.

By day Murphy works for a healthcare publishing company. He enjoys heavy metal music and is an on-again/off-again player of Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games. He is married and lives with his wife and two daughters in Massachusetts. To learn more about his interests and writings please visit his personal blog, The Silver Key.